Cattle Diseases

Bovine Viral Diarrhea in Cattle

Also known as: BVD, Mucosal disease

BVD causes lowered milk production, reproductive losses, an increase in general disease and reduced growth rates

Bovine Viral Diarrhea (BVD) is a viral disease which infects mainly cattle, but can infect sheep, goats, deer and pigs (Hurtado et al., 2003) caused by a pestivirus (similar to the viruses that cause Border Disease in sheep and swine fever in pigs). BVD can have an impact on the herd’s immune and reproductive status (Brownlie, 2005). Due to its varied manifestations and subclinical nature in many herds, the significance of the disease has often been underestimated in terms of its effects on animal health and the economics of the farm.

Cost to a dairy farmer?

BVD causes significant financial losses to affected farms during an outbreak (Pritchard et al., 1989). It is reported that 95% of dairy herds in England and Wales are positive for BVD virus antibodies in bulk milk, with 65% of the herds likely to have suffered an outbreak recently and having persistently infected animals in the herd (Paton et al., 1998). It has been estimated that approximately 1% of cattle are persistently infected with BVD (Paton, 1999).

Dairy herds positive for BVD virus antibodies have an increased abortion rate (Rüfenacht et al., 2001) and have been found to have an increased duration to first calving in heifers (Valle et al., 2001). The reproductive effects of BVD are important economically (Grooms, 2004) with estimates of the cost of infection varying, depending on whether the herd is endemically infected or susceptible. Estimates of significant economic losses in naive herds are provided by Gunn et al., (2004). In beef herds, it has been estimated that BVD infection in a naive herd would cost $53 U.S. dollars per cow per year (Gunn et al, 2004).

What is BVD?

There are two biotypes of BVD virus reported, Type 1 which is endemic in the UK and Type 2 which is rarely reported in the UK (Cranwell et al., 2005), but is a problem in North America. Type 2 BVD infection is associated with more severe clinical signs of hemorrhagic enteritis. Type 1 infection sometimes causes an outbreak of acute diarrhea at the time of introduction into a herd, however the introduction can go totally unnoticed. Long-term effects are at a herd level (See table 1).

| Clinical signs | Long term effects at the herd level |

|---|---|

|

|

How is BVD spread?

BVD Persistently Infected Animals (PIs)

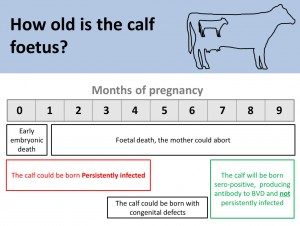

BVD persistently infected animals (PIs) are fundamental to maintaining this disease. It is important that cows do not come into contact with BVD for the first time (naïve cows) during the first 3-4 months of pregnancy. If they do they will give birth to a PI calf. When born these calves may show no sign of infection but they will excrete hundreds of millions of virus particles daily in their saliva, skin, urine and feces throughout the duration of their lives. Only 100 virus particles are needed to transmit infection (Reference: Brownlie 2014 RVC podcast accessed 02/07/2014@19m). The immune system of PI animals recognize the virus particles as self.

Only a minority of PI animals reach adulthood, 50% die within 12 months of age. Many die of mucosal disease before two years of age which is characterized by oral ulceration, diarrhea, pneumonia and interdigital lesions in the feet. It is triggered by the virus mutating into a more virulent form and is rapidly fatal and untreatable. BVD virus has also been identified as an immunosuppressive agent, increasing the risk of infections such as respiratory disease, diarrhea and pneumonia in calves, salmonellosis, interdigital dermatitis and mastitis (Penny et al., 1996; Waage, 2000). This immunosuppression is mainly caused by PI’s in the group but affects in contact animals while transiently infected. Therefore a single PI in a calf pen can cause severe disease outbreaks in the rest of the group.

In infected herds control and eradication of BVD focuses on the identification and elimination of PI animals as the main risk factor for BVD infection in a herd. In uninfected herds the focus should be on preventing the introduction of the disease, mainly by restricting purchases of PI animals and controlling contact with neighboring cattle. The PI animal then infects in-contact animals. Before the introduction of good vaccines, the PI animals were knowingly allowed contact with non-pregnant animals to allow them to be infected and develop natural resistance. However, this method was unreliable and is not recommended as it frequently resulted in disease outbreaks, reproductive loss and sub-optimal immunity in the herd.

Bought-in animals are the greatest risk of disease introduction, either as PI animals or if cows are bought in in-calf, where they may be carrying a PI calf. Another major risk factor for BVD is the introduction of an acutely infected animal into the herd, such as a purchased breeding or fattening animal, a herd member returning from a show or a hired bull. Therefore, all new animals should be tested and/or quarantined on arrival to the herd, especially breeding bulls if their health status is not BVD accredited-free.

Other significant risk factors can be:

- Direct contact with cattle from a neighboring, infected herd (Van Winden et al., 2005).

- Contact with other cloven hooved animals (sheep, deer, pigs)

- Contact with infected materials, such as equipment, boots or clothing, other visitors

- PI bulls can excrete virus in their semen

- There is experimental evidence to suggest that biting flies may also be able to spread BVD (Brownlie et al., 2000)

Control and Prevention of Bovine Viral Diarrhea

BVD is significant in terms of reproductive loss and immunosuppressive effect, and several control options have emerged depending on the cattle density and prevalence of disease.

Diagnosing Bovine Viral Diarrhea

Control and monitoring of BVD infections should be an integral part of the farm’s Herd Health Plan in association with the vet.

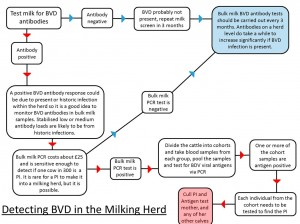

Antibodies to BVD can be easily detected in both blood and milk samples. Antibody tests provide an indication of exposure to BVD virus and are useful when assessing the status of a group of animals at the herd level. Animals who have been exposed to BVD at some point in their life, and/or vaccinated against BVD will have BVD antibodies circulating in their blood (Brownlie et al., 2000).

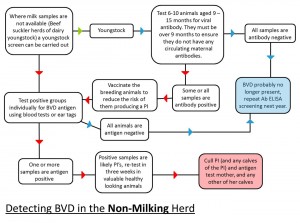

Milk samples can also be examined for the presence of BVD antibodies, such tests on bulk milk only provide an average antibody load for the milking herd, however when monitored regularly (i.e., every 3 months) they are a simple method of obtaining an insight into the level of exposure to BVD. A rise in antibody levels are indicative that the virus is present within the herd more investigation will be needed (See flow diagram).

It is important to remember that PI animals do not generate antibodies for BVD, they do however have viral antigen circulating in their blood, and this can be detected in an antigen ELISA blood test or using a PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction). Therefore in an actively infected herd, cattle which are antibody negative may be PI animals and need to be tested for viral antigen. If positive they are most likely PI animals, but there is a possibility that they are transiently infected (Also known as acutely infected). This means they were naïve, and have been exposed to BVD virus in the past 2-3 weeks causing an acute infection lasting for about 14 days. In this time, the animal will be positive for virus antigen.

In order to prevent misdiagnosing these animals as PIs, they can be re-tested twice after three to four weeks with an antigen ELISA (the PCR stays positive for longer) and both samples positive for viral antigen confirm a PI.

The main reservoir of infection is undoubtedly the persistently infected animal and, as such, the most critical part of the diagnosis and control program (Brownlie, 2005). Persistently infected animals must be removed from the herd immediately (Graham et al. 2015)

Ear Tags

For some time now special ear tags have been developed which take a small section of ear tissue into a small labeled container when applying the tags. These tissue samples can then be tested for BVD antigen. The ear tissue test is not affected by colostrol antibodies and therefore can be done from birth. Main advantages are

- Cheap (cheap lab fees, no vet time, no extra handling)

- Early detection of PI’s

- Helps to establish the status of the dam. If the calf is not a PI, the dam is not a PI.

Vaccinating against Bovine Viral Diarrhea

Eradication alone leaves a herd vulnerable to BVD, and therefore vaccination should be considered to maintain the herd BVD-free if biosecurity failures are a possibility (mainly due to neighboring cattle contact or buying in stock). Vaccination does not modify the status of or eradicate PI animals. For optimal results, breeding animals should be vaccinated before the breeding season to ensure maximum protection is conferred for the first few months of gestation to prevent the creation of a PI (Sexton, 2008).

Vaccination to control and prevent BVD is now both possible and cost effective (Brownlie et al., 2000), and may be the preferred option if high levels of biosecurity are not possible to maintain and disease prevalence is high. However, vaccination can still mask underlying infection (Brownlie, 2005). Traditionally vaccines available in the UK contain the Type 1 strain of BVD, although this has been shown to be effective in minimizing the effects of Type 2 BVD infection (Makoschey et al., 2001). A new live vaccine contains type 1 and type 2 BVD antigen.

Several European countries or regions have established BVD control or eradication programs including the Shetland Islands in the UK. BVD eradication leads to improved herd health and the ability to sell disease free stock, which may be important to some pedigree herds. Establishment and maintenance of a disease-free herd is dependent on a high standard of biosecurity, which must be assessed in each herd’s circumstances.

Treating Bovine Viral Diarrhea

There is no treatment for subclinical BVD or acute mucosal disease. Support therapy in the form of fluids and anti-inflammatory agents can be used for acutely infected animals. PI’s whether diseased or apparently healthy should be removed from the herd as soon as possible.

Bovine Viral Diarrhea and Welfare

There are no specific welfare considerations with regard to BVD, although control of disease should be considered as it impacts significantly on the health of the herd. Animals suffering from acute mucosal disease should be humanely destroyed.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

There is considerable debate as to whether the UK should attempt to eradicate BVD on a nationwide basis (Brownlie, 2005).

BVD eradication and accreditation

To eradicate BVD the following summarizes the steps necessary:

- Establish a genuine closed herd policy (no animals should enter the herd without being tested for BVD, unless they come from a BVD-free accredited herd).

- Carry out an initial assessment of the herd status (this is done by blood sampling a number of youngstock while bulk tank milk samples can be used in dairy herds to gain initial information)

- The exact eradication program varies according to the farm situation, but an example is given below.

To remain free of BVD, it is important to consider the following:

An unexposed herd is extremely susceptible to introduction of infection. Therefore, herd health security needs to be totally reliable:

- Closed herd policy

- Double fencing

- Screening of bought-in animals including show animals and common grazing

- Where breaches of biosecurity cannot be ruled out, the herd should be vaccinated as an ‘insurance policy’

Control of endemic BVD

- If accreditation is not the aim, the herd’s disease status should be monitored regularly as part of the Herd Health Plan. This is easily undertaken by quarterly bulk tank milk sampling in dairy herds and an annual youngstock screen in beef suckler herds and dairy youngstock. The same controls on bought-in animals should also apply (i.e. test and quarantine)

- If a herd is suffering from increased levels of calf disease or other infectious diseases, this may be due to the immunosuppressive effect of BVD infection and the status should be established

- Vaccination should be considered. The long-term success of BVD control depends on identification and removal of PI animals, which should be considered in parallel with vaccination

- Vaccination should ideally include all breeding animals including heifers and bulls prior to breeding. Annual vaccination is necessary to maintain immunity

- Cull PI animals (these animals spread the infection in the herd and are at risk of suffering a major disease crisis at some point of their life). The culling should be carried out as soon as the results are known. After this, vaccinate the breeding animals, with annual revaccination

- It is now possible to vaccinate young calves against BVD infection as part of a combined vaccine against respiratory pathogens (including IBR, RSV and PI3). This vaccine is not suitable to provide long term immunity and fetal protection in breeding animals and must therefore be followed up with later vaccinations

British English

British English

Comments are closed.