Poultry Diseases

Gumboro Disease

Also known as: Infectious Bursal Disease

At one time the disease was considered as primarily affecting commercial broiler flocks. A virulent strain appeared in Europe in 1987 and since then it has become an important disease of layer and breeding flocks. Widespread vaccination is now conducted, and the immunocompetence status of breeder flocks and hatcheries is determined by the degree of exposure to the virus. Flocks maintained under strict biosecurity are particularly susceptible to field exposure as they would not previously have been exposed to the disease.

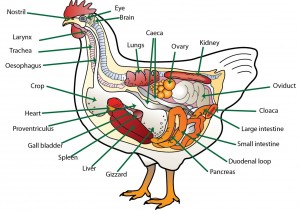

The virus which causes Gumboro disease usually affects the lymph cells in the cloaca, tonsils and spleen.

Image source: www.poultryhub.org

The virus is excreted from infected birds for 10–14 days and is highly infectious. There are a range of vectors including wild birds, vermin and humans. Disease severity can depend on virus virulence, levels of maternally derived antibody (MDA), age and breed. Although offspring may be immune for a period, a drop in the level of maternal antibodies can mean increased susceptibility particularly to new virulent strains. Thus, at every generation, breeders assess IBD status and develop appropriate vaccination programmes in order to achieve the highest level of immunocompetence.

There is some evidence of breed differences in susceptibility: for example, the Leghorn has been shown to be less resistant than other breeds (Santivatr, 1981)and susceptible at up to 18 weeks. There is also increased resistance in older birds, as the cloacal bursa has become involuted.

Lesions detected at post-mortem are indicative of the disease. These include swelling of the cloacal bursa (of fabricus) and hemorrhages of thigh and breast muscles.

Virus neutralizing antibodies develop more slowly in new-born birds, and Vervelde and Davison (1997) concluded that age-related susceptibility to IBDV in chickens may be due to immunological factors, cytokine release or blood factors (Vervelde and Davison, 1997). In broilers, the disease occurs mainly in birds aged 3-4 weeks, with no apparent seasonality (Meulemans et al., 1980). Symptoms of the acute form of the disease in 3-6 week old chicks include white watery diarrhea and soiled vents. Infected birds may be depressed with ruffled feathers and closed eyes and tend to lethargic and anorexic.

Although mortality rates may reach 50%, they are commonly in the range of 0-20% and tend to peak 3-5 days after infection. Gross sub-clinical forms of the disease are often seen in chicks of less than 3 weeks. These can be without obvious symptoms apart from reduced growth. These sub-clinical cases can result in the greatest economic losses as a consequence of destruction of immature lymphocytes resulting in immuno-suppression. These immuno-suppressed birds do not respond well to vaccination against diseases such as Newcastle disease, Marek’s disease, infectious bronchitis and coccidiosis.

The influence of subclinical infections of IBDV and other viral diseases on broiler production has been investigated in Denmark. It was concluded that sub-clinical infections do not significantly affect flock performance, whereas there was a profound influence of breed, diet, population density and contents of whole wheat grain in the feed (Jørgensen et al., 1995).

Aflatoxins (a type of mycotoxin) have been shown to have the effect of making IBD a much more severe disease and of changing the symptoms (Chang and Hamilton, 1982).

Control and Prevention of Gumboro Disease

If Gumboro is an issue, vaccination is the most effective control method, either through enhanced MDA in parent stock or through active immunity by means of direct vaccination of chicks. Vaccination policy against Gumboro disease tends to vary by area and the degree of challenge – in cases where the level of challenge is low, birds can develop immunity and vaccination will not be required. However, where vaccination is used, all protocols strive to provide passive protection to the hatching chick, followed by active immunization and a series of boosts in layer and breeder flocks (Saif, 1998).

If there is a challenge to birds from Gumboro, live vaccines are normally administered through drinking water or eye-drops to chicks at 12-21 days. Saif (1998) refers to unpublished data that casts some doubt on this controversial practice. A live vaccine at 4-10 weeks, followed by an inactivated oil-adjuvanted vaccine at approximately 16 weeks, may be used on parent birds in order to achieve high levels of MDA. Repeated vaccination of chicks is practised in some flocks to counteract declining levels of MDA. It is important that vaccination of chicks is given when MDA levels are low so as to avoid MDA neutralizing the effect of the vaccine.

Removal of the virus from contaminated sites can be difficult, as large quantities are excreted and the virus is stable. An all-in all-out housing policy, coupled with stringent disinfection with formaldehyde and iodophors, can prove effective in reducing challenge to levels and enhancing the impact of vaccination.

Spread of the disease has been associated with the use of infected manure on fields adjoining poultry housing. It is therefore advisable to locate poultry manure away from poultry houses and to store for more than 3 months. Protecting manure heaps from wildlife could also be desirable in controlling infection. Outbreaks of recent virulent epidemics of IBD have been spread rapidly by litter taken from infected houses. There are MAFF and Department guidelines concerning manure handling.

Routine blood testing can be conducted to assess the immune status of flocks.

Treating Gumboro

Gumboro disease cannot be successfully treated, so if there is a risk of this disease, vaccination is the best policy. The virus is resistant to a number of disinfectants.

Pattison (1993) recommends the following disinfection procedure after contagious and infectious disease:

- The buildings should be closed and isolated from all visitors

- The bedding, litter and all areas in intimate contact with the birds should be sprayed with a disinfectant at adequate concentration

- The litter should subsequently be removed from the building and may be burnt or buried so there is no possible contact with poultry or other livestock

- Portable equipment and fittings should be given the same treatment, preferably in the house, and later be taken out and aerated

- The floors and lower part of the walls are treated with a detergent disinfectant

- Surfaces should then have a disinfectant applied with a wide spectrum of activity, capable of killing all types of pathogens present

- It may be advisable to skim off the top few inches of the soil around a heavily infected area

- The approaches to the building should be treated with disinfectant; foot dips should be provided for personnel and wheel-dips for vehicles

Good Practice based on Current Knowledge

- If there is a risk of Gumboro, vaccinate all birds at a week old

- Operate an ‘all-in, all-out’ policy between batches of birds

- Maintain high standards of hygiene, particularly with regard to disinfection between batches

- Store poultry manure for at least 3 months before spreading

- Do not spread manure on land used for poultry

- Protect manure heaps from wildlife

British English

British English

Comments are closed.