Sheep Diseases

Lameness in Sheep

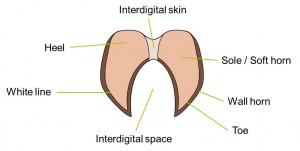

Includes the following conditions: Foot Abscess, Foot Rot, Contagious Ovine Digital Dermatitis (CODD), Interdigital Dermatitis (OID), Granuloma, Scald, Shelly Hoof, White Line Separation

Lameness in sheep is a common and persistent disease, reported in flocks in all sheep producing countries. It is a major welfare concern and causes large economic losses. Persistent lameness can lead to reduced weight gain, metabolic diseases in pregnant ewes, reduced birthweight of lambs, mis-mothering and poor colostrum production by ewes (Harwood et al., 1997; Henderson, 1990).

Lameness is often seen in flocks at pasture and under more intensive conditions. Lameness varies from mild and transient, to severe and persistent (Egerton, 2007). Recording which animals are persistently lame and do not respond well to treatment, is crucial in controlling infectious lameness in a flock. Farmers Weekly, AHDB Beef and Lamb and MSD Animal Health have put together a useful ‘Five Point Plan’ to tackle lameness, which incorporates reducing disease challenge, building resilience and establishing immunity. More can be read about it here.

Accurate early diagnosis of the cause of lameness is an essential prerequisite for decisions on the level of intervention required to correct the problem (Egerton, 2007). Lameness is mainly caused by bacterial infection of the hoof (except Shelly Hoof), which causes pain, lesions and sometimes abscesses and these are outlined in the table below:

| Disease | Part of the foot affected | Associated bacteria | Infectious or Non-infectious | Lameness severity* |

| Foot-rot** | Interdigital skin, sensitive laminae, sole, horn, wall horn | (Virulent) Dichelobacter nodosus OID flora (see below)

Fusobacterium necrophorum (Maboni et al, 2016) |

Infectious | 0-4 |

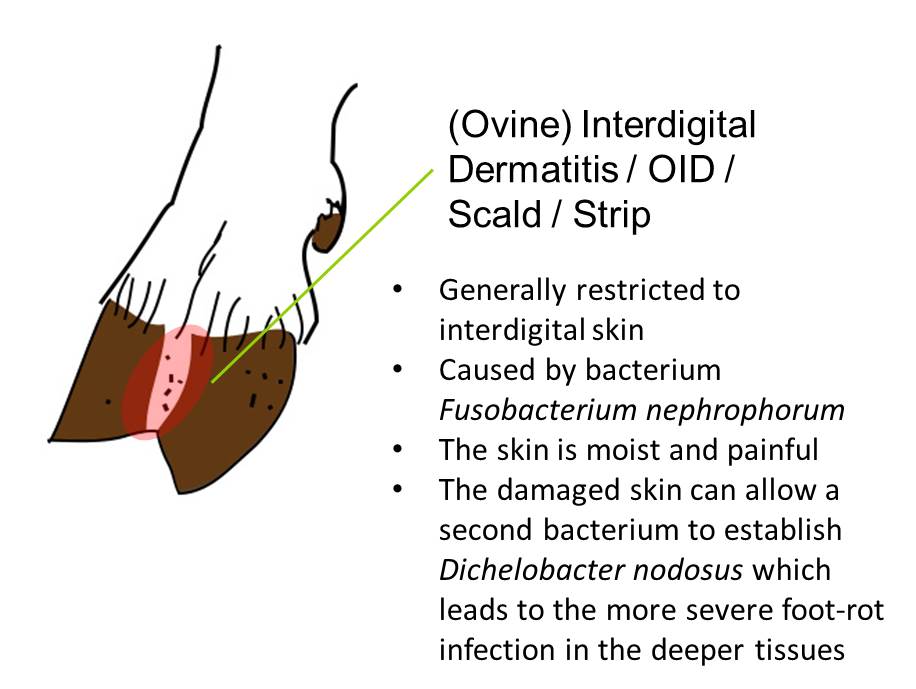

| Interdigital Dermatitis / Ovine Interdigital Dermatitis (OID) / Scald | Interdigital skin | Fusobacterium nephrophorum, Actinomyces pyogenes | Infectious | 0-1 |

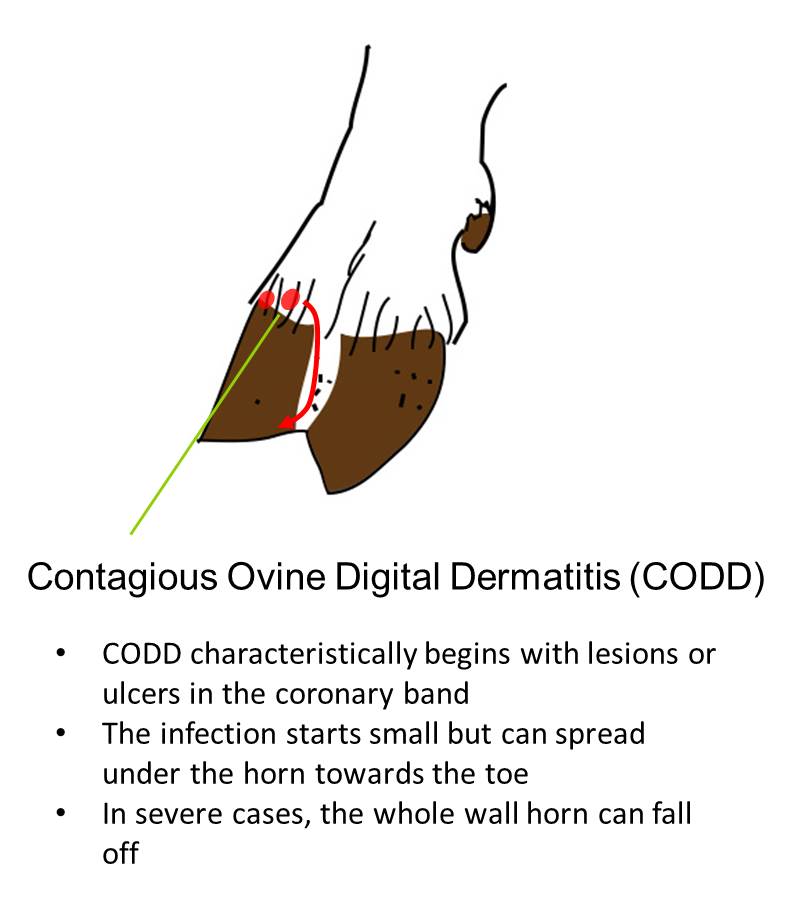

| Contagious Ovine Digital Dermatitis (CODD) | Skin of coronary band, sensitive laminae of wall horn | Spirochaetes | Infectious | 3 |

| (Toe) Granuloma | Often the toe | Non-specific | Non-infectious | 0-4 |

| Heel or Toe Abscess | Pedal joints, claws become swollen | Non-specific | Non-infectious | 4 |

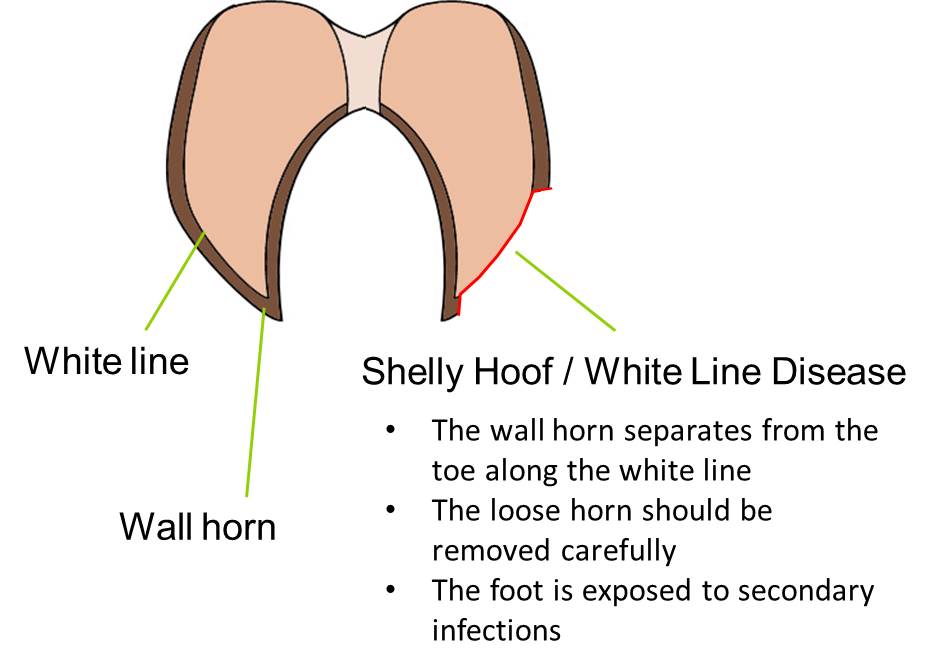

| Shelly Hoof / White Line Separation | The wall of the hoof | Not bacterial | Non-infectious | 0-3 |

*Lameness severity 0 = normal gait, 4 = severe lameness

** Known as contagious foot-rot in the USA. In Australia, foot-rot is defined as either benign or virulent depending on the virulence of D. nodosus. All cases of foot-rot that under-run the hoof horn are considered to be virulent foot-rot (Green and George, 2008).

(This table has been adapted from Egerton, 2007 p273 Table 39.1)

Scald and Foot-rot

Foot-rot is a complex, highly contagious disease caused by a synergistic infection of two anaerobic bacteria, Dichelobacter nodosus and Fusobacterium necrophorum, and has a characteristic foul-odor, often accompanied with a grey pus (Green and George, 2008). D. nodosus cannot invade the dermis without prior damage to the foot (Beveridge, 1941) and it cannot persist in the environment for longer than 7-10 days under optimal moisture and temperature conditions.

Foot-rot is a complex, highly contagious disease caused by a synergistic infection of two anaerobic bacteria, Dichelobacter nodosus and Fusobacterium necrophorum, and has a characteristic foul-odor, often accompanied with a grey pus (Green and George, 2008). D. nodosus cannot invade the dermis without prior damage to the foot (Beveridge, 1941) and it cannot persist in the environment for longer than 7-10 days under optimal moisture and temperature conditions.

There are two hypotheses for the role of F. necrophorum within the footrot complex: either F. necrophorum is important to establish interdigital dermatitis before D. nodosus infection, and hence initiates the disease (Roberts and Egerton, 1969), or F. necrophorum is involved in the persistence and severity of footrot, once the under-running lesion has developed, playing a role as an opportunistic, secondary pathogen (Witcomb et al, 2014, 2015). The subspecies of Fusobacterium necrophorum subsp. necrphorum is thought to have a higher pathogenicity than the subspecies funduliforme, which may tell us more about the involvement of this bacteria in the complex (Maboni et al, 2016).

F. necrophorum infection on its own causes a condition called scald, strip or ovine interdigital dermatitis (OID) and it affects the skin between the claws only, in the interdigital space. Scald is often odorless, the skin is moist and painful, and sometimes a greyish/white fluid is present. Scald is not invasive, and causes no separation of the horn from deeper tissues. It is usually found in sheep that are continuously exposed to wet pastures (Egerton, 2007).

The damage to the skin from scald, however, allows D. nodosus to invade and colonize deeper layers, where it feeds on collagen. Once D. nodosus is established, F. necrophorum can advance deeper into tissues too, where it will contribute to further inflammation and tissue damage, caused by the action of its exotoxins.

Outbreaks of scald (OID) are typically seen in lambs on pasture and among ewes housed on straw. Wet conditions predispose interdigital skin to OID.

Foot-rot spreads more readily in warm, moist weather outdoors (Cross, 1978; Cross and Parker, 1981) and when sheep are housed (Henderson, 1990). Under optimal temperature conditions, D. nodosus can survive for up to 6 weeks in horn hoof clippings (Whittington, 1995).

Risk factors for foot-rot

- Bought-in sheep are the most likely source of D. nodosus infection

- Breed – All breeds of sheep are able to contract foot-rot, although it has been suggested that some more primitive breeds of sheep found in the UK, such as Soay, are less susceptible, and popular breeds used in Australia and New Zealand such as Merinos are highly susceptible (Emery et al., 1984)

- Farm environment – transmission from one sheep to another will always occur via the surface on which the sheep are kept; therefore the environment is very important in the transmission of foot-rot within a flock (Green and George, 2008)

- Damage to the foot integrity, caused by:

- Wet conditions

- Coarse grass

- Foot trimming – not only by damaging the hoof, but also through the transmission of bacteria from one animal to another on clippers.

Click here to read about the control and prevention of scald and foot-rot

Contagious Ovine Digital Dermatitis (CODD)

Contagious ovine digital dermatitis (CODD) differs clinically from foot-rot caused by D. nodosus and often fails to respond well to accepted treatment practices for foot-rot, which is usually the first indication that CODD is present in the flock.

Contagious ovine digital dermatitis (CODD) differs clinically from foot-rot caused by D. nodosus and often fails to respond well to accepted treatment practices for foot-rot, which is usually the first indication that CODD is present in the flock.

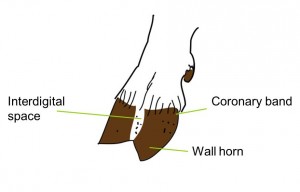

The main difference between conventional foot-rot and CODD, is the origin of the initial lesion at the coronary band. Infection starts at the junction of the coronary band and the wall of the hoof, and infection invades the sensitive laminae underneath the horn (Egerton, 2007). It starts small and causes separation of the wall of the hoof and the coronary band. It spreads downwards towards the toe. The acute infection of the foot is often associated with the presence of spirochaetes. Diagnosis can be complicated when there is a simultaneous infection of foot-rot and CODD.

CODD usually affects both claws, the cleft and often the skin above the hoof. The horn may completely detach, but unlike ‘normal’ foot-rot, the coronary band where new horn is produced may be permanently damaged, resulting in the animal needing to be culled (Harwood and Cattell, 1997; Harwood et al., 1997; Winter, 1997). There is often rapid shedding of the whole horn case, leaving a raw digital stump. The condition may spread rapidly within a flock, so a diagnosis should be sought to differentiate CODD from foot-rot and other foot conditions. If diagnosis is unclear, a veterinarian should be contacted.

Click here to read about the control and prevention of CODD

Shelly Hoof

The white line is the site at which the horn of the wall of the hoof joins that of the sole. It is a naturally weak area in the horn, and there are two problems that can occur here, both eventually leading to lameness, but not usually infectious:

- The first problem is an extensive degeneration of the white line. This is called shelly hoof and is characterized by pockets impacted with dirt and other debris, where the hoof wall has become separated. Mild cases, not necessarily leading to lameness, are very common. More severe cases result in abscesses and lameness (Scott and Henderson, 1991).

- The second problem occurs when a toe abscess develops along the white line. Pus forms and the animal becomes acutely lame. Some animals suffer repeated attacks, probably due to a permanent defect in the horn.

Click here to read about the control and prevention of shelly hoof

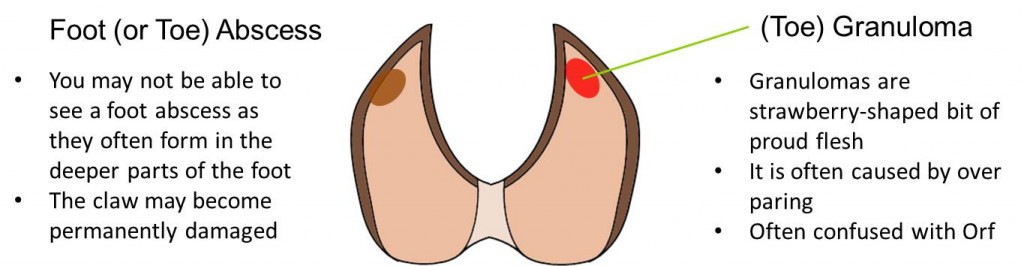

Foot Abscess

Foot abscesses can form in the deeper parts of the hoof and often affect the pedal joint. Once infection is established in the joint, permanent damage is inevitable. The affected claw becomes swollen and very painful, with visible signs of necrosis. Pus may burst out through the coronary band or between the claws. The animal may become permanently lame due to a permanent deformity (Egerton, 2007).

Click here to read about the control and prevention of foot abscesses

Granuloma

A granuloma is a strawberry-shaped area of proud flesh, which grows at the site of damage to the foot. The overlying horn is unable to grow back normally. It is often caused by over rigorous foot trimming, which has led to bleeding, although other causes of injury to the foot may play a role. It usually causes an overgrown, misshapen hoof, because the animal does not put its full weight on the foot due to chronic lameness (Scott and Henderson, 1991). Click here to read about the control and prevention of granulomas

Other Conditions Causing Lameness in Sheep

There are also many other reasons for lameness including:

Control and Prevention of Lameness in Sheep

Foot Trimming

It is no longer advised to routinely trim diseased and healthy feet as it is have been shown to exacerbate foot-rot and scald (Green et al., 2007). It is also no longer advised practice to trim the hoof horn into the dermis, as it may lead to a granuloma (Kaler and Green, 2008). However, routine inspections and careful trimming is advised in cases where there is loose horn that may allow mud and debris to get stuck in the foot. If foot trimming is necessary, make sure the clippers are sharp and are disinfected between feet to minimize the spread of any bacteria, also collect and dispose of any hoof clippings as they can harbor harmful bacteria such as D. nodosus.

Foot Baths

Sheep standing in a foot bath. This should be carried out routinely, as it has been shown to reduce the incidence of scald (Interdigital Dermatitis) This image is taken from Eblex BRP Sheep Manual 7

Routine foot bathing is useful to treat and prevent scald, but unless the animals stand in it for 15 minutes at a time, it is not particularly effective in treating foot-rot.

See Control and Prevention of Scald and Foot-rot for more information.

It has been estimated that half the costs associated with foot-rot are for preventive measures, with the remainder lost from production and treatment (Nieuwhof and Bishop, 2005). Although any lame sheep should be a cause for concern, in practical terms, a prevalence of 5 per cent or more should prompt an investigation into the cause, and the implementation of a control program, in conjunction with your vet (Winter, 2004).

Some farmers may be unaware of some of the proven methods of foot-rot control and probably allocate greater resources to the treatment of foot-rot, rather than to its prevention. Topical treatments, vaccination and parenteral antibiotic therapy all have a role in treating sheep with advanced foot-rot infections, but prevention of severe infections is best achieved by the timely implementation of control programs. These are usually based on foot bathing and vaccination.

For control programs to be effective it is essential that the pathogenesis and epidemiology of foot-rot is understood and that control methods are implemented at appropriate times in the season, depending on climatic and pasture conditions (Abbott and Lewis, 2005).

The Five Point Plan to Tackle Lameness

The UK levy body for the beef and sheep industry, AHDB Beef and Lamb, joined forces with Farmers Weekly and MSD Animal Health to jointly put together a five point plan to tackle lameness from all angles, giving the flock the best chance of staying clear of the condition.

The guidance can be downloaded here: Sheep Lameness 5 point plan MSD.

Control and Prevention of Scald and Foot-rot

Preventing scald helps prevent foot-rot. Scald cannot be easily eradicated from the flock, because the causative bacteria F. necrophorum occurs naturally in the soil. In contrast, foot-rot can be eliminated from a flock, as D. nodosus can only survive for 2-3 weeks on pasture.

The best, and most cost-effective conventional method for the control and prevention of scald and foot-rot is regular foot bathing with 10% zinc sulfate heptahydrate or formalin 3%, in combination with the prompt identification of lame animals and treatment with appropriate antibiotics (Cross and Parker, 1981; Parajuli and Goddard, 1989; Salman et al., 1988). Having a closed flock can make it easier to eradicate foot-rot from the flock and keep the flock free from the disease, additionally, the reduced stocking rates will decrease the foot-rot challenge.

Housing increases the spread of the disease, therefore sheep should be free of foot-rot when brought-in. Any lame sheep need to be treated and isolated from the rest of the group. Regular foot bathing throughout the housed period should prevent an outbreak of foot-rot. Adequate straw bedding should be maintained to keep feet dry and clean and lime spread on the floor, especially around water troughs, will help dry and sterilize the bedding and reduce the risk of infection (Henderson, 1990).

Persistently infected sheep need to be identified and those that do not fully respond to treatment should be culled, as they are a source of infection to the rest of the flock.

Click here to read about the treatment of scald and foot-rot

Vaccinating against Foot-rot

Footvax is a commercially available vaccine used to reduce the number of infected sheep and it is worth considering as part of a control strategy where levels of foot-rot in the flock are high. However, it can be curative as well as preventive. A persistent reaction can occur at the injection site and may produce local pigment changes in the wool. Therefore, vaccination should be avoided within 6 – 8 weeks of shearing or 6 months before sale or showing (The Veterinary Formulary, 1998). It should be noted that once vaccinated with footvax, these animals cannot be treated with 1% moxidectin I the future.

Elimination of Foot-rot in Western Australia

A virulent foot-rot (caused by the virulent strains of D. nodosus) elimination program was undertaken in Western Australia on a flock-by-flock basis, and it is now estimated that as few as 0.7% of all premises in Western Australia have virulent foot-rot (Mitchell, 2003). Western Australia has predictable periods of hot, dry weather, with a typical low rainfall period from spring through to the end of the summer, which naturally prevents survival, thus transmission of virulent D. nodosus (Green and George, 2008). The mean temperature for this period is over 86°F, which contributes to the arid environment.

During the wetter autumn and winter, farmers undertook the basic control and treatment measures for virulent foot-rot, including foot bathing, topical antibiotic treatments and vaccination. Surveillance during this period was ongoing and all sheep with clinical signs of virulent foot-rot (lame or sound) that did not respond to treatment were culled. If foot-rot was discovered, the farm was quarantined until confirmed clear (Green and George, 2008; Mitchell, 2003).

The elimination program requires the hot, dry period of zero transmission to be successful, as at the start of spring, there were no sheep with clinical signs. Any non-apparent, but infected sheep should become diseased and were removed. Reintroduction via brought-in stock is prevented as animals were only purchased from certified foot-rot free farms (Green and George, 2008).

Control and Prevention of CODD

The greatest risk of a CODD outbreak in a flock is from bough-in stock. Sheep with CODD can be carriers and not show obvious signs of lameness. Therefore, careful attention to foot health in purchased sheep before addition to the flock is warranted (Egerton, 2007). Click here to read about the treatment of CODD

Control and Prevention of Shelly Hoof

Routine feet inspections will pick up any cases of shelly hoof early. Careful foot paring may prevent shelly hoof becoming infected (Scott and Henderson, 1991).

Click here to read about the treatment of shelly hoof

Control and Prevention of Abscesses

Sharp stones and prickly and abrasive flora can puncture the hoof allowing bacteria to enter the foot, resulting in an abscess. Prevalence of toe abscesses in flocks is usually very low, and is non-infectious. Heel abscesses however, are more prevalent and have been associated with scald caused by continuous exposure to wet pastures and fecal contamination (Egerton, 2007). Click here to read about the treatment of foot abscesses

Control and Prevention of Granuloma

Most granulomas are caused by over-trimming the feet, however chronic exposure to moist conditions and previous footrot have been suggested to be major contributing factors to granulomas (Egerton, 2007). Shepherds of flocks with a history of granuloma cases should be given a training session in foot trimming. Granulomas are often confused with orf.

Click here to read about the treatment of granulomas

Treating Lameness in Sheep

In order to manage and minimize flock lameness, farmers need to routinely inspect feet, separate those that are showing signs of lameness and then treat them appropriately. Photograph by Mike Suarez.

Key steps for treating lame sheep, as recommended by AHDB Beef and Lamb:

- Yard the sheep

- Separate all those showing signs of lameness

- Identify the lesion

- Treat as appropriate

- Mark the sheep and record ear tag

- Repeat after 14 days and add another mark if lameness persists

- Cull any sheep that become lame for a third time

Details of treatments for the different types of lameness can be found in each relevant section below:

Treating Scald and Foot-rot

After treatment for infectious lameness, the treated animals should be turned out on to ‘clean’ pasture that has been free from livestock for at least 2 weeks. This will prevent the transmission of D. nodosus, the virulent bacteria that causes foot-rot. Photograph by Mike Suarez.

The causal organism of scald is found in the natural environment and cannot be eliminated. If foot-rot is present on the farm, but only small numbers of sheep are affected in a group, these can be treated with colored oxytetracycline (antibiotic) spray, provided the treated animals are not immediately returned to wet grass (Harding et al., 1981). For larger numbers, the only practical answer is foot bathing, then movement on to pasture that has been free from livestock for at least 2 weeks.

As scald infection is superficial, the animals do not have to stand in the footbath for very long. Walking sheep through foot baths 6m long, 10cm deep containing 10% zinc sulfate heptahydrate or 3% formalin should be adequate (Egerton, 2007). Prickly pasture should be avoided, as this may cause interdigital abrasions, predisposing the interdigital skin to infection (Whittington, 1995).

In the case of foot-rot, the animals need to stand in the foot bath much longer (10-15 minutes), but as this is not always practical, infected and uninfected sheep should be sorted and treated separately. After foot bathing, sheep should stand on a hard surface for an hour to let the feet dry. Treated animals should be turned out on grazing which has been free from sheep for at least two weeks.

Individual cases of foot-rot should be promptly identified and treated individually with injectable antibiotics and colored oxytetracycline sprays. Long-acting oxytetracycline is very effective in treating the disease and requires less handling than short-acting oxytetracycline (Grogono-Thomas et al., 1994). A meat withdrawal period must be observed.

Although not widely used, maggot therapy has shown to be successful in the treatment of foot-rot and foot scald in sheep, forming new layers of healthy tissue over the wounds following a single application (Kočišová et al., 2006).

Treating CODD

The farm environment is critical in preventing lameness. Hard tracks full of stones and debris can damage the animals feet. Tracks such as the one in this image are much softer on the feet. Photo courtesy of Animal Welfare Approved.

Seek veterinary advice as no individual treatment is recommended and conventional antibiotics and footbaths used for true foot-rot are not entirely effective. However, topical application of a solution of lincospectin soluble powder has shown promising effects (Egerton, 2007), as has treatment of individual animals with Tilmicosin injection (Angell et al, 2016).

Treating Shelly Hoof

Careful foot trimming to remove any loose flaps should prevent the build-up of dirt and debris in sheep with shelly hoof. If the build-up of pus does occur, the treatment is the same as for toe abscesses.

Treating Foot Abscesses

Sheep with toe abscesses should be carefully pared along the white line, and this will usually reveal a dark mark. Sometimes pus will be released. The horn should not be pared so deeply that bleeding is caused. Difficult cases may need poulticing for a couple of days to soften the horn and speed recovery. Further paring may have to be carried out to remove under-run horn as the hoof heals, though carefully and not excessively. If not treated, the pus eventually bursts out at the coronary band and the animal gradually recovers.

Foot abscesses that affect the pedal joint are serious and require veterinary attention. It may be better to cull the affected animal, but the decision whether or not to amputate will partly depend on the foot involved. If the front feet are involved, the animal stands a better chance of a reasonably normal life.

Treating Granulomas

Granulomas need veterinary attention, as it is necessary to anesthetize the foot before trimming to expose the granuloma. The granuloma is then removed and the base cauterized. If done correctly, this will restore the foot to near normal (Scott and Henderson, 1991). Repeat cases should be culled.

Lameness in Sheep and Welfare

Lameness is associated with physiological and behavioral responses, indicating that it is a severe form of chronic stress in sheep (Dwyer and Bornett, 2004).

Most cases of lameness in sheep are easily prevented and should be done so through good husbandry methods. Lameness in sheep is a major welfare problem and affects two of the Five Freedoms promoted by the Farm Animal Welfare Council, as it not only causes pain to the animal, but can also cause a depression in feed intake. This depression of feed intake leads to a general loss of condition and predisposes the animal to other conditions, such as pregnancy toxemia, low birth weights and poor colostrum production. These lead to lambs suffering hunger, hypothermia and disease (Harwood et al., 1997). Lameness in breeding rams causes pain, thus reducing work rate during the breeding season (Henderson, 1990).

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

As foot-rot is a major welfare concern, a strategy to reduce lameness should be a priority and part of every farm’s Flock Health Plan. The control and prevention strategy should include:

- Regular foot bathing with zinc sulfate heptahydrate or formalin, followed by yard time, where their feet can dry before being turned out

- Avoid regular foot trimming

- Any bought-in sheep should be foot bathed and quarantined for at least 3 weeks before entering the main flock

- Do not accept lame animals when buying stock

- Ideally check every animal for early signs of foot-rot or CODD

- Treat all cases quickly, even mild ones, as disease can spread very rapidly, but make sure the correct drug is given for the disease

- In the case of foot-rot, foot abscesses or granulomas the farm vet should be contacted immediately

- Long pastures with prickly plants should be avoided, as the interdigital abrasions caused by these pastures make the sheep prone to interdigital infection

A written health and welfare plan, which covers the yearly production cycle, should be prepared for each flock. This should be developed with appropriate veterinary and/or technical advice and reviewed and updated annually. The plan should assess vaccination policy, control of internal and external parasites and foot care as a minimum. Pasture management should form an integral part of disease control, especially in the case of internal parasites and foot-rot. Identification of high-risk periods for disease will encourage quick implementation of control strategies.

Guidelines in the case of an outbreak of foot-rot

It is possible to eradicate foot-rot from a flock but this requires careful planning, good fences, commitment and dedication. The best time to start an eradication program is in summer, after weaning and before breeding.

In a small flock

- In small flocks with a foot-rot outbreak, individual cases should be treated with long-acting oxytetracycline in consultation with the farm vet

- The sheep should be foot bathed in a 10% zinc sulfate heptahydrate solution for 15-30 minutes, followed by an hour of yard time to dry out and then turnout on to clean pasture

- The foot bathing should be repeated every two to three weeks

In a large flock

- Sort sheep upon inspection into infected and uninfected groups. The uninfected group can be given a short foot bath and turned out to clean pasture.

- Severe cases in the infected group may need an injection with long-acting oxytetracycline (in consultation with the farm vet).

- The infected group should be foot bathed in a 10% zinc sulfate heptahydrate solution for 15-30 minutes, followed by an hour of yard time to dry out and then turnout on to clean pasture. The infected group must be kept separate from the uninfected group, so that treatment can be repeated every 2-3 weeks until the animals are cured

- Flocks with a severe foot-rot problem may benefit from vaccination to reduce the number of infected sheep

- Persistently infected sheep, which do not fully respond to treatment, should be culled as they are a constant source of infection.

- Any bought-in sheep need to have their feet checked and bathed upon entry to the farm

- These sheep need to be grazed separately for at least 3 weeks, and foot bathed again before entering the main flock

It has previously been suggested that flocks badly affected with footrot or CODD could use blanket Tilmicosin treatment metaphylacticly. However, this is not best practice in line with responsible antimicrobial usage and some more recent reviews suggest it to be no more effective than promptly identifying and treating individual lame animals. (Angell et al. 2016).

British English

British English

Comments are closed.