Sheep Diseases

Coccidiosis in Lambs

Also known as: Eimeria

Several Eimeria species have been identified that cause disease in different hosts (Cattle, pigs, poultry), and although the majority of sheep carry coccidian, only two species (E. crandalis and E. ovinoidalis) are recognized as being clinically pathogenic in the UK. Both of these are found in the ileum, but E. ovinoidalis also occurs in the caecum and colon. Both impair the absorptive capacity of these parts of the gut, thereby provoking scours. E. ovinoidalis also damages the gut’s capacity for regeneration, thus precipitating a more severe and prolonged disease.

Eimeria Lifecycle

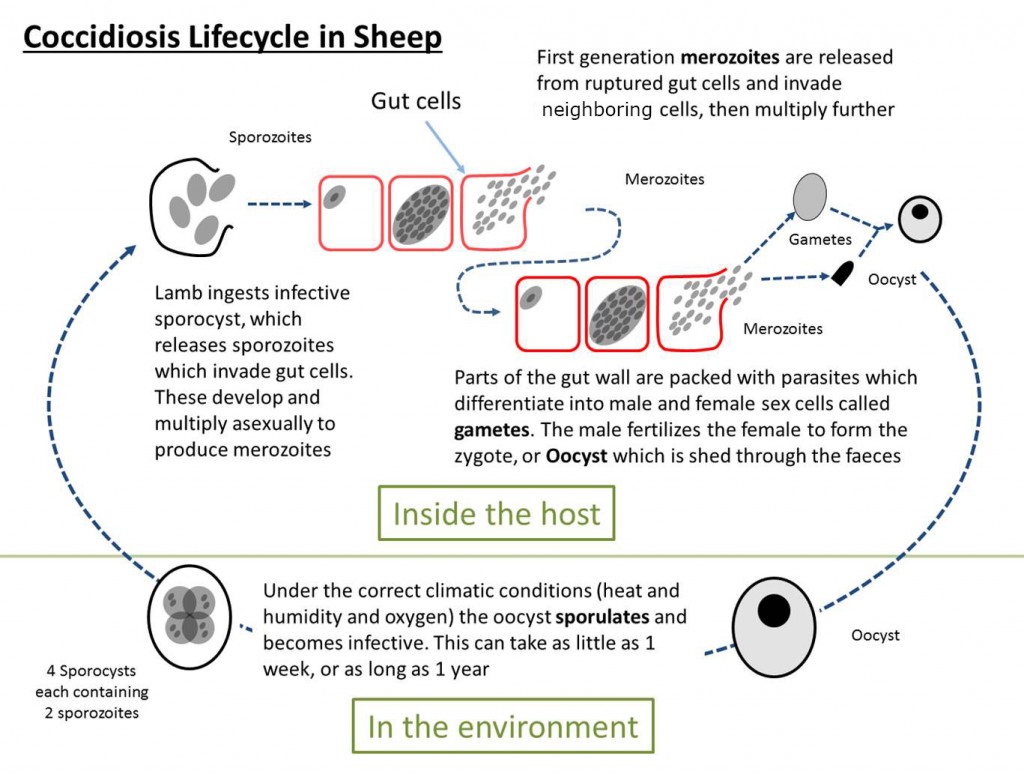

The lifecycle takes between 2 – 4 weeks depending on the species of Eimeria.

- Oocysts are shed in the feces of infected animals

- They undergo rapid multiplication (called sporulation) until each oocyst contains 4 sporocysts, and each sporocyst contains 2 sporozoites. Sporulation outside the body may take 1-4 days in ideal conditions but can take several weeks in cooler weather. Oocysts can survive on the ground for up to a year

- When a lamb swallows oocysts, they break open in the gut, releasing high numbers of parasites, which invade the gut wall

- Each parasite grows and multiplies by repeated asexual division to produce a hundred or more daughter parasites

- The daughter cells break out and invade fresh areas of the gut wall and repeat this process

- Within 10 – 14 days the parasites will have multiplied by up to a million fold

- By this stage of infection, parts of the gut wall are packed with parasites which develop into male and female sex cells

- The female sex cells are fertilized and secrete an oocyst wall around them, then drop off the gut wall to be excreted in the feces

Adapted from (Blewitt and Angus, 1991; Taylor et al., 2007)

Virtually all sheep flocks are infected with coccidia, but only some lambs develop clinical disease (Catchpole et al., 1975). Clinical coccidiosis occurs when damage to the gut is sufficiently severe to cause dysfunction. This normally occurs at the beginning of the parasite’s sexual multiplication stage, when parasite numbers reach their peak. The lambs may suffer from dullness, inappetence, diarrhea (with or without blood), dehydration and weight loss (Taylor et al., 2007). Coccidial oocyst output is highly correlated with reduced weight gains.

Two circumstances lead to clinical coccidiosis:

(i) Massive ingestion of infective oocysts due to a highly infected environment and/ or

(ii) A significant asexual multiplication in the host, in relation to a lowered resistance of the animal (Chartier and Paraud, 2012)

The source of the initial outbreak of clinical coccidiosis is likely to be either residual contamination in the environment (oocysts can overwinter on pasture in low numbers) or low levels of oocyst shedding by other sheep, providing a continuous source of infection. The level of the environmental infection, particularly with pathogenic species, is probably the most important factor, but other factors, such as nutritional and climatic stress, may be involved. It is difficult to predict the occurrence of clinical coccidiosis, as some flocks are troubled by it every year while others, with similar management systems, are not (Blewitt and Angus, 1991).

Control and Prevention of Coccidiosis in Sheep

Outdoor lambing accompanied by lower stocking densities reduces the risk of an outbreak of coccidiosis, as it reduces the environmental contamination with infective oocysts.

The first priority in controlling coccidiosis is to avoid circumstances that allow infection to build up to dangerously high levels. The low stocking density and outdoor lambing management systems often applied by low-input farmers reduce the risk of an outbreak of clinical coccidiosis. However, sheltered areas for the protection of animals against bad weather can become contaminated with coccidia and need to be kept dry and clean.

Housed lambs should be provided with adequate clean litter and bedding, although there is some evidence that exposure to oocysts early in life may help to build up immunity (Gregory, 1995; Gregory and Catchpole, 1989; Gregory et al., 1989).

Late lambs should not graze pasture previously used by earlier lambs. Creep feeders should be moved regularly to prevent poaching and the build-up of infection in the environment.

Preventative anti-coccidial drugs, such as products containing amprolium, chlortetracycline, decoquinate and sulfadimidine, are available for the control and prevention of coccidiosis in flocks where the disease has been a problem in previous years. Diclazuril and toltrazuril are also licensed for the treatment and prevention of clinical coccidiosis in lambs. Treating in the case of expected high oocyst challenge should not be done on the day of turnout but 10-14 days after. Treatment may need repeating. Studies carried out on treating on the basis of expected high challenge have shown lambs have reduced oocyst output, higher growth rates and less diarrhea (Diaferia et al., 2013).

However, the use of prophylactic anti-coccidial drugs for the control and prevention of coccidiosis is not sustainable, and the emphasis should be on changes in management to control and prevent the disease (Berriatua et al., 1994).

Coccidia oocysts are extremely resistant to environmental stress, including exposure to disinfectants. Oocysts are, however, killed by heat, direct sunlight and drying, so housing should be cleaned at high temperatures to avoid the environmental build-up of sporulated oocysts.

Diagnosing Coccidiosis in Sheep

Due to the rapid multiplication and high shedding capacity of coccidia, high fecal oocyst counts of non-pathogenic species are often mistakenly used to diagnose severe coccidiosis infection, when in fact diagnosis should be based primarily on history and clinical signs. Fecal oocyst counts can help complete the picture, especially when speciation is available, but oocyst numbers can be grossly misleading when considered in isolation (Taylor et al., 2007).

Treating Coccidiosis in Lambs

Oral drenches specifically for the treatment of lambs with coccidiosis are available. Your vet can advise on the most appropriate product.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

- Maintain low stocking densities

- Keep shelters and creep feeders dry, clean and move them regularly to prevent poaching

- Provide adequate clean litter and bedding for lambs kept indoors

- Graze late lambs on pasture not previously grazed by earlier lambs

- Treat affected lambs on the basis of fecal oocyst counts in combination with history and clinical signs

British English

British English

Comments are closed.