Sheep Diseases

Liver Fluke in Sheep

Also known as: Fasciola hepatica

Fasciolosis is an economically important and potentially fatal disease of sheep which can be associated with particular regions throughout the world directly linked to the habitat of an aquatic mud snail . In Europe the snail species naturally infected with Fasciola hepatica (Liver fluke) is Galba trunculata (previously known as Lymnaea trunculata), and in the USA multiple fresh water snail species belonging to the genus Lymnaea have been reported to harbour infection (Dunkel et al., 1996). Climatic and hydrological factors play an important part in the epidemiology of the disease which is directly linked to the habitat of the intermediate mud snail host. Liver flukes are not host-specific. Fasciolosis does not just afflict sheep but all grazing animals are susceptible to infection including cattle, deer, rabbits and horses. There are also between 2.5 and 17 million reported cases of human fasciolosis from eating aquatic vegetation (mainly wild watercress) contaminated with infective metacercariae (Ghildiyal et al, 2014).

Grazing Management

Snail Habitat Management

Monitoring for Fluke Infection

Treatment Options

Good Practice

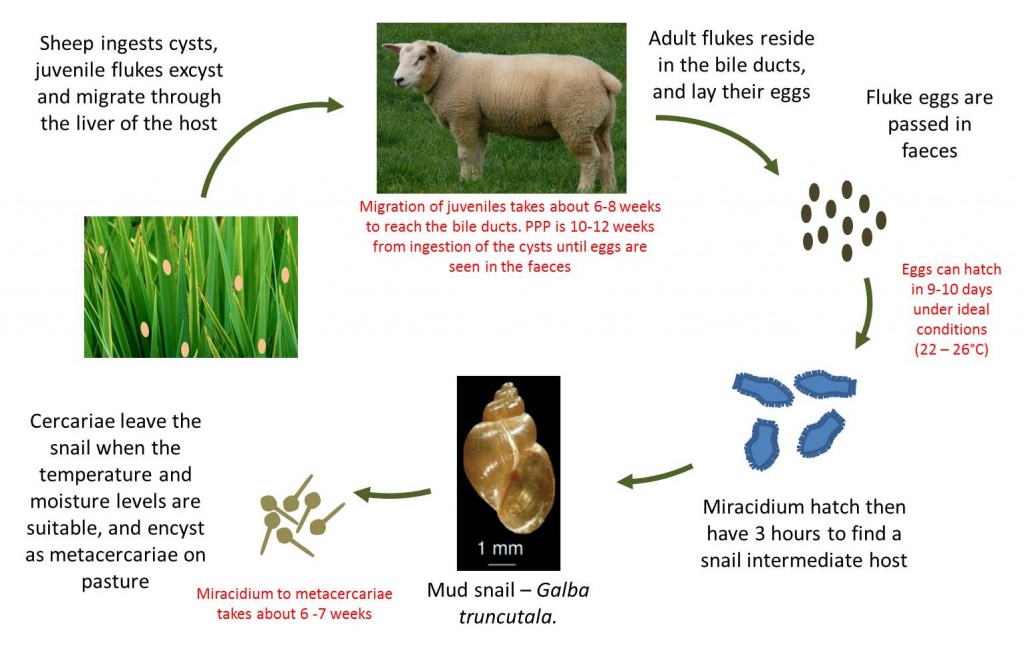

Liver Fluke Life Cycle

- The adult fluke resides in the bile ducts in the liver of the definitive host

- The eggs they shed are passed down the bile ducts and into the intestine to be excreted in the faeces. One fluke can pass between 5000 and 20,000 eggs per day

- When environmental conditions are suitable (wet and >10⁰C), the fluke eggs hatch into small infective larvae (miracidia)

- The miracidium actively seek a specific mud snail intermediate host (Galba trunculata in Europe)

- In the digestive tract of the aquatic snail, the miracidia develop into cercaria

- From one miracidium, six hundred or more cercariae are produced, and emerge from the snails after about 6 weeks, depending on the climate

- The cercariae swim to attach themselves to herbage where they lose their tails and secrete a tough cyst wall to become metacercariae

- At 12-14 °C, up to 100% of metacercariae can survive for six months, though only 5% survive for 10 months. For prolonged survival, the relative humidity needs to be above 70%

- Once ingested by sheep, the immature fluke burrow through the gut wall and pass to the liver. They are voracious feeders and migrate through the liver parenchyma to reach the bile duct, where they mature. Egg laying commences 10-12 weeks after the initial infection, which is important to note when using faecal eggs counts to diagnose infection.

The length of the complete life cycle of Fasciola hepatica (Liver fluke) is long and varies depending on the season as it requires a definitive host (cattle or sheep) and an intermediate host (mud snail), though the minimum period for the whole life cycle is 5 – 6 months. The time from ingesting infective metacercariae cysts on the pasture to adult flukes laying eggs in the bile ducts is about 10-12 weeks. Fluke thrives in wet summers and is wholly dependent on the presence of the mud snail (Galba trunculata in Europe)

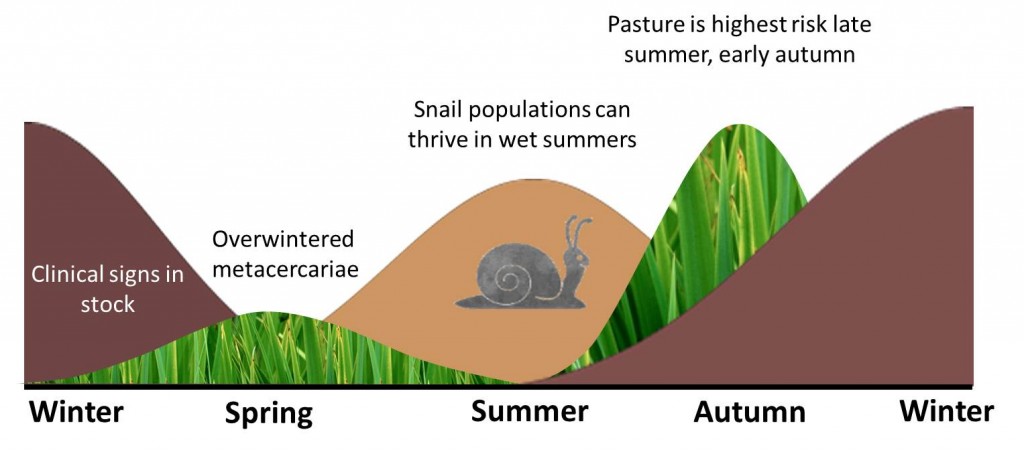

The mud snail requires water and warm conditions for reproduction and survival. The ‘summer’ infection of snails results from the hatching of overwintering eggs passed from the sheep (or eggs passed) in the spring. The metacercariae then appear on pasture from August to October.

A less pronounced ‘winter’ infection of snails is from eggs shed by the sheep in the autumn. It is thought that larval development in the snails ceases during the winter months and commences again in spring resulting in pasture contamination with metacercariae in May and June. Winter infection is significant prolonged survival of the parasite as the infected snail hibernates carrying infection through the winter.

In sheep fasciolosis can be classed as either acute or chronic.

Acute fasciolosis is highly pathogenic in sheep. Acute infection is often seen in younger animals and is dominated by the effect of simultaneous migration of immature flukes in the liver causing bleeding and severe liver damage. If many thousand metacercariae are ingested sudden death can occur.

Chronic fasciolosis is a result of prolonged intake of cysts and leads to the progressive loss of body condition. Death is rare in well nourished sheep. The clinical signs of chronic fasciolosis are variable and depend upon the number of metacercariae ingested, but often include:

- Weight loss

- Anaemia

- Bottle jaw

- Diarrhoea

- Constipation (Torgerson, 1999).

Definitive diagnosis is based on post mortem examination. Fluke egg counts in faeces can be useful indicators of infection, although false negatives do occur as eggs can only be detected in faeces 10-12 weeks post-infection. Also the adult fluke reside in the bile ducts, so any eggs laid need to travel down the bile ducts into the intestines, before being passed out with faeces. This process is sporadic. A coproantigen test on faeces is also available which will detect fluke before a standard faecal egg count can. Blood tests are also available and can be very useful at certain times of the year, although they only indicate previous exposure, not current infection.

Control and Prevention of Liver Fluke in Sheep

Fluke prevention and control should be part of an integrated approach (in conjunction with the farm vet) to parasite control in the Flock Health Plan on any farm. Control should be farm specific and farmers must consider all livestock together as liver fluke infects cattle, sheep and other grazing animals (including rabbits and deer). Fluke control measures can be divided into 3 sections:

1. Grazing management

2. Snail habitat management

Grazing management – avoid grazing high risk pastures

Summer infection of snails primarily leads to winter disease in sheep. Under optimal conditions Galba trunculata snails can lay 3000 eggs per year. These eggs hatch and mature within 2 weeks, and snails can be sexually mature within 3 weeks. One snail can produce 25,000 descendants within 12 weeks. Aquatic mud snails hibernate throughout the winter then re-emerge in spring. When the temperature is 10°C, the cercariae are released from the snail, and encyst on pasture as infective metacercariae. Once ingested the juvenile flukes take about 6 – 8 weeks to react the bile ducts, where they mature into adult flukes and begin feeding and reproduction.

Pasture is considered to be highest risk between late summer and autumn due to the summer infection of snails and their sheer fecundity. This leads to disease being most prevalent from autumn onwards through the winter. These risks are much lower following a hot dry summer.

Winters in Northern Europe and similar temperate climates are generally too cold for liver fluke to develop. However, low levels of metacercariae can survive overwinter on the pasture if the climate conditions are favourable. This along with autumn infected snails hibernating, then shedding cercariae in early spring can lead to high enough levels of metacercaria on pasture to cause low levels of clinical disease in sheep throughout the summer.

Keeping stock off areas that were wet in late summer early autumn (when the snails released the cercariae) will help reduce the incidence of disease.

Grazing management – Avoid co-grazing

Unlike most other parasitic diseases of ruminants, liver fluke is not host species-specific and grazing sheep with cattle on high risk pasture can potentially amplify the disease. As sheep shed higher numbers of liver fluke eggs than cattle, co-grazing could benefit sheep but could be detrimental to cattle.

Snail habitat management – Fence off wet areas

Unlike with parasitic gastroenteritis, liver fluke can only be found in areas where the mud snail is present. The preferred habitats of Galba trunculata are shallow water, ditches, banks of slow moving streams, spring swamps and reeds. In addition watering troughs can provide suitable habitats (Knubben-Schweizer and Torgerson, 2014).

Wet, marshy, shallow water with a low pH, surrounded by unconfined pasture makes the ideal habitat for Galba trunculata. Reeds are often seen in this type of habitat.

Identify this ‘flukey’ pasture, i.e., wet, marshy, muddy areas, often with lots of rushes growing there, and fence this area off. It will be costly in the short term but could be beneficial in the long term. However, it is clear that this is not possible on many farms as it would mean a significant loss of grazing.

Snail habitat management – Drainage of wet areas

Drainage of wet areas that are suitable habitats of the mud snail can be highly effective, but again will be costly in the short term but will help with liver fluke control in the long term. However drainage may not be permitted under some environmental schemes as it could be detrimental to other wildlife habitats.

Monitoring for infection – Faecal egg counts

Regular faecal samples should be taken from sheep to determine the liver fluke burden on the farm, however FECs are limited as they will only confirm an infection (if eggs are seen in the faecal samples) but do not give an indication of parasite burden and if eggs are not presence in the faeces, it does not confirm there is not a fluke infection. Only adult fluke produce eggs, and as they reside in the bile ducts, the eggs are only passed out sporadically. This aside composite FECs from 10 or more animals can be useful to monitor incidence of liver fluke on farms. Due to the seasonality of liver fluke and the fact that they commence shedding eggs 10-12 weeks post infection, FECs are more useful at certain times of the year (e.g., winter and spring).

Monitoring for infection – Blood testing

While FECs are not particularly sensitive, but will confirm infection if positive, individual blood serology detects antibodies against liver fluke from two weeks post infection.

Monitoring for infection – Coproantigen tests

This is a relatively new commercially available test which detects fluke digestive enzymes in host faecal samples. It is useful to diagnose individual cases but has not been fully evaluated on mob faecal samples. However, coproangtigen tests will detect fluke infection about 3 – 6 weeks before FEC.

Monitoring for infection – Abattoir reports

Abattoir reports can be used as an indication of infection on a farm, however they usually condemn the liver and report with active or historical fluke infection. Also a liver condemned for fluke does not always mean a high level of infection; it could just mean that one adult fluke was seen. Nevertheless it is an indication that fluke (and the mud snail!) is on the farm, and further investigation is required.

Monitoring for infection – NADIS parasite forecast

Fasciolosis forecasts by NADIS animal health are based on the Ollerenshaw predictive model that relates meteorological data to the probable incidence of fasciolosis in particular years. These are published on the NADIS website here.

Quarantine of stock – Biosecurity

Buying in stock brings with it the risk of disease onto a farm that was not present before. This includes the introduction of resistant parasites. Quarantine of bought-in stock should always be undertaken as a biosecurity measure and if there is any doubt over the fluke status, treatment should be considered.

Treating Liver Fluke in Sheep

Fasciola hepatica is not (definitive) host specific, it can infect both cattle and sheep, although has more severe effects in sheep. It can also infect horses, mice, rabbits and deer. There are also between 2.5 and 17 million reported cases of human fasciolosis from eating aquatic vegetation (mainly wild watercress) contaminated with infective metacercariae (Ghildiyal et al, 2014).

Flukicide treatments are the most common method of control but they do not have persistent activity so will not prevent re-infection, and triclabendazole resistance has been reported in sheep and cattle (Mitchell et al., 1998; Moll et al., 2000; Thomas et al., 2000, Gordon et al., 2012). All flukicides will effectively kill adult fluke, some (nitroxynil and closantel) will kill the late immature stages but only triclabendazole (which is used extensively in the sheep sector because of the high mortality of acute fasciolosis in sheep) is the only product effective against very early juvenile stages (2 weeks post infection onwards).

There has been increasing interest in plants with molluscicidal (snail-killing) activity, such as some Eucalyptus spp. (Hammond et al., 1994) and the latex of Euphorbiales spp. (Singh and Agarwal, 1988). However, this research is in its early stages and there is no work quantifying the effect of these plants in the field. More research is required.

Certain sciomyzid fly larvae have been shown to eat mud snails, and this has been put forward as a possible method for the control of the intermediate snail hosts. Work has been conducted in Ireland on Ilione albiseta to see if this insect could be exploited in the control of fasciolosis (Gormally, 1987, 1988a, 1988b).

Research is being undertaken to develop a vaccine against secretary proteins, which would prevent fluke survival. There are still significant problems to overcome, but there do appear to be some realistic prospects of producing a vaccine against F. hepatica (Mulcahy et al., 1999, Jarayaj et al., 2010). This will be useful to farmers who do have a continuous problem with fasciolosis.

| Age of fluke (Weeks) | ||||||||||||||

| Flukicide | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| Albendazole | 50-70% | 80-99% | ||||||||||||

| Oxyclosanide | ||||||||||||||

| Nitroxynil | 50-90% | 91-99% | ||||||||||||

| Closantel | ||||||||||||||

| Triclabendazole | 90-99% | 99-99.9% | ||||||||||||

This table has been adapted from Fairweather and Boray, 1999

Flukicides – Strategic treatments to reduce pasture contamination

Strategic dosing schemes suppress egg output at critical times of the year. January treatment of sheep will reduce fluke burden and chronic infection, as well as reduce pasture contamination. It will prevent sheep shedding eggs at the start of spring when snail populations are coming out of hibernation and primed for infection.

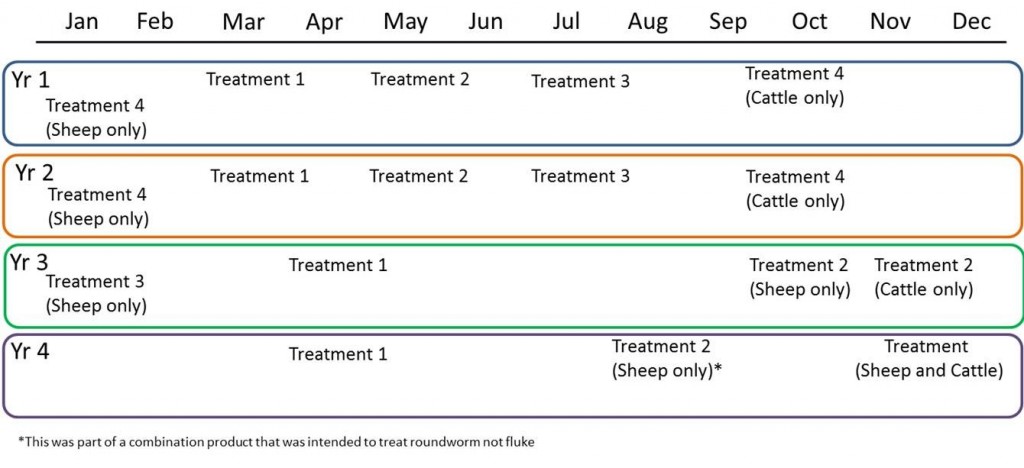

One scheme reported to help reduce fluke burdens over a period of four years, such that overall treatment frequencies and fluke burdens could be reduced in both sheep and cattle (Parr and Gray, 2000). This would be most useful in an environment where the fluke challenge is high. The diagram below illustrates their treatment schedules for both cattle and sheep

The diagram illustrates the four year treatment strategy demonstrated by Parr and Gray (2000) in which they lowered the incidence of fasciolosis and thus reduced the number of doses for cattle and sheep annually based on the principle of strategic treatments maintaining low level infections in both stock and the mud snails.

Flukicides – Therapeutic treatment

Therapeutic treatments are for those animals showing signs of disease, and for animals who are not showing overt signs of disease but have sub-clinical disease which is affecting production and may predispose to other diseases. Following clinical cases of fasciolosis, it is likely that the whole flock is suffering from the infection, although there may be large individual differences. This can be checked by faecal egg counts. Regular treatments are initially given at 12-13 week intervals to reduce the intensity of infection in the flock. The number of treatments can be reduced following the decline in prevalence of liver fluke (Torgerson, 1999).

Fluke burdens can vary enormously on the same farm from year to year, therefore constant surveillance and monitoring should be encouraged, by means of forecasting, faecal sampling and abattoir feedback.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

- Fence off snail habitats or exclude stock from flukey areas at periods of high risk of infection where possible

- Keep an eye on the fluke forecast for the year (NADIS)

- If necessary, work out a strategic worming regime against liver fluke with the farm vet

- Flocks with clinical cases of fasciolosis require regular treatments with a flukicide that kills both mature and immature fluke until prevalence is reduced

- Faecal egg counts are advisable on a regular basis to monitor disease trends

- Where possible, obtain feedback from abattoirs where sheep are killed to obtain information on liver fluke prevalence

- It may be possible to treat animals on an individual or group basis following faecal egg counts rather than treating the whole flock. This will require close observation and regular faecal egg counts during the risk period.

Further guidance on liver fluke control, prevention and treatment can be found in the SCOPS (Sustainable Control of Parasites) guidelines

American English

American English

Comments are closed.