Sheep Diseases

Toxoplasmosis in Sheep

Contaminated feed is considered to be the most likely source of infection for sheep. Keeping cats away from stored feed will minimise the risk of infection.

Toxoplasmosis is caused by the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. The organism is an intestinal coccidium of cats, with a wide range of warm-blooded intermediate hosts, including sheep, in which it can cause considerable losses during pregnancy (Buxton, 1991). Toxoplasmosis causes heavy economic losses to the sheep industry worldwide (Innes et al., 2000).

Toxoplasmosis is a zoonotic disease and although not common in humans, it can present a food safety issue and infection in pregnant women can lead to abortion, stillbirth or serious disease in the newborn. As a provision, pregnant women should avoid close contact with sheep during the lambing period. (Further guidance about pregnant women and contact with sheep can be found here: http://www.nhs.uk/chq/pages/934.aspx?CategoryID=54).

Toxoplasma can also cause severe disease in people with HIV, or other conditions that suppress the immune system.

The Life Cycle of Toxoplasma

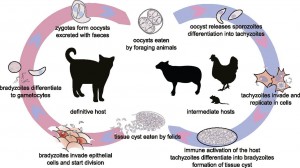

The life cycle of Toxoplasma can be divided into two stages;

- The asexual cycle with little host specificity i.e., the stage that occurs in sheep, humans, rodents and birds

- The sexual stage of the life cycle, confined to the intestinal epithelial cells of cats, which results in the production of oocysts.

The asexual life cycle of Toxoplasma

Tachyzoite stage:

Toxoplasma gondii life cycle. The sexual stage that occurs in the definitive feline host is shown on the left, with the non-host specific asexual stage on the right. This image is a modified image taken from www.elifesciences.org

- Cats shed millions of unsporulated oocysts in their faeces, these take 1-5 days to sporulate depending on the climatic conditions

- The sheep ingests a sporulated oocyst

- In the gut the sporozoites are released and they penetrate the intestinal wall and migrate via the lymphatic and portal systems

- Tachyzoites penetrate host cells and become surrounded by a vacuole – Toxoplasma gondii can infect cells in the reproductive system, central nervous system, lung, liver and muscle tissue

- The tachyzoites multiply asexually by a process called ‘budding’

- Once 8 – 16 tachyzoites have accumulated, the cell ruptures and new cells are infected

Some cases result in the death of the host, but more usually the host develops immunity to the infection and chronic infection is established, which is called the bradyzoite stage.

Bradyzoite stage:

- Antibodies are produced by the host’s immune system and any extra cellular parasites are eliminated

- The antibodies limit the invasiveness of intracellular tachyzoites to new cells, resulting in the formation of cysts which are found most frequently in the brain and skeletal muscle

- These cysts contain between a few and many thousands of organisms called bradyzoites, which grow very slowly – this is the latent form. If immunity wanes, cysts may rupture releasing bradyzoites.

Adapted from (Taylor et al., 2007).

The sexual stage of the life cycle of Toxoplasma

- The sexual stage of the life cycle starts when a (usually) young cat ingests food containing cysts, such as a rodent

- The walls of the cysts dissolve in the stomach and small intestine

- The released bradyzoites penetrate the epithelial cells of the small intestine and form gametocytes over the 3-15 days following infection

- The formed microgametes are released and swim to and penetrate macrogametes

- The resulting oocysts, each containing a fertilised gamete, are passed out of the cat and sporulate within 1 – 5 days (Frenkel, 1973; Taylor et al., 2007).

Cats (young strays in particular) are the primary source of infective oocysts as they shed millions in their faeces.

Cats can shed millions of oocysts, but only for a period of about 8 days, after which they generally do not excrete oocysts again. Ingested oocysts and tachyzoites can also infect cats, but in this case oocysts are produced in reduced numbers, and even then by only half the animals (Buxton, 1991; Gethings et al., 1987). A study in the USA reported that 60% of cats tested were serologically positive for Toxoplasmosis (Taylor et al., 2007).

Oocysts can survive for months and contaminate pasture, grain, hay and water, which if consumed by pregnant sheep that have not encountered Toxoplasma before, can trigger infection in the developing foetus (Buxton, 1990). Typically, a ewe produces a weak or stillborn lamb two to three days early, often accompanied by a small, mummified foetus. Weakly lambs do not usually survive, as they often have brain damage. The placental membranes will appear normal, but characteristically there will be multiple white spots 1-2 mm in diameter in the cotyledons (Rodger and Buxton, 2006). The outcome of infection depends largely on the stage of pregnancy when the ewe was infected and the age of the foetus.

| Early Pregnancy | Infection in early gestation leads to foetal death and resorption, leaving the ewe barren. |

| Mid Pregnancy | Infection in mid-gestation results in the parasite becoming established, first in the placenta and then in the foetus. The ability of the foetal immune system to resist the disease is age-dependent. Infection in mid-pregnancy may sometimes result in the death of a lamb but spare its twin and hence allow the pregnancy to survive. Infection will, however, be established in the surviving placenta and progressively damage the cotyledons. In some cases the placenta is so compromised the foetus dies. In others the lamb survives but is born with brain damage resulting from lack of oxygen due to a damaged placenta. |

| Late Pregnancy | After 70 days, the foetus becomes progressively more able to combat the disease, and infection during the latter part of gestation would normally be successfully controlled in the foetus by its more advanced immune system. The placenta would become infected and damaged, but with less time before lambing, the degree of damage would not be sufficient to cause major issues. |

Control and Prevention of Toxoplasmosis

Infected cats shed millions of oocysts in their faeces. A likely source of infection is a place where cats like to live, such as in a hay or straw barns. Pregnant ewes should be prevented from eating contaminated feed or bedding.

Cats play an essential role in the spread and prevalence of toxoplasmosis. It is difficult to explain the widespread infection in sheep, but it is thought that pregnant ewes are most commonly infected during periods of concentrate feeding at tupping or lambing, when the stored food has become contaminated with cats’ faeces and millions of oocysts (Taylor et al., 2007). Therefore a primary control measure should be to protect feedstuffs from access by cats.

Practical control measures depend upon the proportion of the flock that is infected. A ‘clean’ flock should be prevented from ingesting food and bedding contaminated by cats, particularly young cats (Gethings et al., 1987). Male cats should be neutered to limit the size of cat population and reduce numbers of young cats. However, chronically infected ewes are resistant to subsequent challenges.

In the past, in flocks in which a large number of ewes were already infected, there was a case to be made for attempting to expose young, non-pregnant replacement stock and uninfected bought-in animals to a contaminated environment 2-3 months before tupping; however identification of a contaminated environment is difficult. It is likely to be an area where cats live, as well as pasture spread with manure from such areas (Faull et al., 1986a, 1986b). Exposing naïve sheep to infected sheep/environment relies on older sheep having been significantly exposed to have developed complete natural immunity. This cannot be proven until the subsequent breeding season.

It is safer and more cost effective to opt for a vaccination strategy, and there is a live vaccine now available, which induces very good immunity after only one injection (Buxton, 1993; Buxton et al., 1991b). The best advice is to talk to your vet about confirming diagnosis and planning a vaccination programme. Vaccinal immunity lasts several years, so a booster is not needed every year, but vaccinating incoming stock and replacement ewes will rapidly reduce disease incidence.

However, the emphasis of prevention should still be on management measures, particularly by ensuring the flock is not exposed to toxoplasmosis, and preventing access to feedstuffs by cats.

Treating Toxoplasmosis

Once an outbreak of toxoplasmosis has started, there is little that can be done other than to observe sensible precautions by disposing of dead lambs and infected placentas and disinfecting contaminated pens.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

Abortion in sheep due to toxoplasmosis must be differentiated from other infectious causes of abortion, including infections with chlamydia (enzootic abortion), salmonella, border disease and Bluetongue. Toxoplasmosis infection in sheep can be confirmed by immunofluorescent staining of antigens in foetal tissues.

- Control the farm cat population by treating with drugs to suppress oocysts shedding

- In the case of an outbreak, dispose of dead lambs and infected placentas and disinfect contaminated pens

- A ‘clean’ flock should be prevented from ingesting food and bedding contaminated by cats, particularly young cats

- In flocks in which a large number of ewes are already infected, a whole flock vaccination programme should be started and susceptible young, non-pregnant replacement stock should be vaccinated prior to the tupping period

American English

American English

Comments are closed.