Goat Diseases

Johne’s Disease in Goats

Also known as Mycobacterium avium, MAP and Paratuberculosis

Johne’s disease is a contagious, chronic, sometimes fatal infection that primarily affects the small intestine of ruminants (Sardaro et al., 2017). It is caused by Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP). The intestine walls thicken, preventing the normal absorption of food causing the animal to utilise fat and muscle reserves, leading to wasting and starvation of the animal (Animal Health Australia). MAP is a global problem believed to be capable of infecting and causing disease in all ruminants (e.g., cattle, sheep, goats, llama, and deer) both in captive and free-ranging living conditions (Sardaro et al., 2017). In goats the disease causes chronic enteritis, eventually expressed as progressive weight loss and associated clinical signs (Nielsen and Toft, 2008).

Johne’s Facts

- The primary route of infection is by kids ingesting infected faeces

- The Johne’s organism (MAP) can survive in the environment for many months

- A single animal can shed millions of bacteria every day

- There is no treatment for Johne’s disease

Risk factors for Johne’s Disease caused by MAP infection in goats adapted from (Sardaro et al., 2015). The risk factors can be sub-divided into animal, farm and managerial factors.

How is Johne’s disease spread?

MAP is spread via ingestion of faeces and milk from infected animals and potentially via the placenta in pregnant animals and in the semen in infected sires (Ayele et al., 2004). Ingestion of faecal material from an infected animal occurs via the teat of an infected nanny, or ingestion of manure contaminated pasture, water, supplements or hay (Windsor, 2015).

MAP is excreted by infected animals before clinical signs appear, although bacterial numbers increase once clinical signs have developed. A single goat will shed millions of disease-causing bacteria at one time. It is believed that most infections occur during the first day of life and originate from the dam or by ingestion of faeces in the birthing area. However clinical signs generally don’t start to appear until later in life. Infected goats can appear to look healthy but still be shedding of bacteria into the environment every day. Once the infection become clinical, the number of bacteria shed is thought to be in the millions. These bacteria are thought to survive on pasture for at least seven months.

After ingestion of infected faeces or milk, MAP invades the small intestine via the lymphatic tissue in the intestinal mucosa, where it multiplies over the next 2-3 months and spreads to the draining lymph nodes. The outcome of the infection depends on both the immune response of the infected animal and the dose of the initial infection, as well as the strain of bacteria (McKenna et al., 2006).

Biosecurity is key in preventing Johne’s Disease from entering your herd

Animals can also become infected by grazing land used by other MAP-infected animals. There is a large reservoir of MAP in the environment as it has been reported in a number of domestic and wildlife species including sheep, goats, rabbits, deer and cats (Palmer et al., 2005).

Ruminants are infected in the first few months of life, usually by the faecal-oral route. Following infection MAP remain silent for a number of months in the small intestines or the lymph nodes, mainly hidden in phagocytic cells called macrophages. Infected intestinal macrophages burst and MAP spreads widely to different sites in the body including the uterus and mammary glands (Mercier et al., 2016).

Diagnosis is determined by immunological tests designed to detect MAP antibodies, of specific DNA detection using Polymerase Chain Reaction, MAP isolation from faecal or tissue cultures, or post-mortem detection of lesions in lymph nodes or intestines (Nielsen and Toft, 2008).

The cost of Johne’s disease

Johne’s disease can lead to large economic losses on a farm due to:

- Decreased milk production

- Costs involved with diagnosis and disease control

- Culling of affected animals

- Lower carcass value at slaughter (Mendes et al., 2004).

- Grazing on pasture that has been reseeded on prepared soil (other than direct drilling) as it is likely to have a lower level of contamination

- Keep feed such as hay or pellets off the ground (in troughs, racks etc.)

- Spell pasture for 12 months by introducing a cropping cycle if possible

A recent study in Italy (Sardaro et al., 2017) assessed the economic impact of MAP infection on farm profit efficiency on semi-extensive dairy sheep and goat farms. Profit efficiency is defined as the ability of a farm to achieve the highest possible profit given the prices and levels of fixed factors (Ali and Flinn, 1989). They found that all farms were profit inefficient (i.e., no farm was maximising profits); however this effect was worsened on farms with MAP infection. Feed, veterinary intervention and labour costs had the greatest effect on profitability. Farmer education, access to credit and fewer family members participating in farm duties also affected profit (Sardaro et al., 2017).

Control and Prevention of Johne’s in Goats

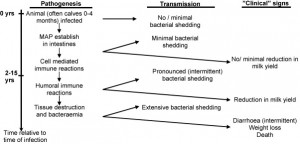

Schematic presentation of various stages of MAP infection and their effects from (Nielsen and Toft 2008). It shows that pathogenesis (i.e., the ability to cause disease), transmission (i.e., ability to spread and infect others) and clinical signs all progress with age.

The three main approaches to eradicate or reduce the impacts of Johne’s disease in herds are:

- Introduce management changes to decrease transmission of MAP

- Apply a test and cull strategy to eliminate the sources of infection

- To develop a vaccination strategy, vaccinating replacement stock (Windsor, 2015)

1. Introduce management changes to decrease transmission of MAP

Management of susceptible stock and their environment will help to minimise the risk of spread within a herd. Newly born kids can be ‘snatched’ from their mothers so they cannot ingest infected milk or faeces. These animals need to be fed MAP-free colostrum and milk. They need to be kept and maintained in a clean environment, and isolated from the potentially infected herd (Windsor, 2015). All of these in combination with a high standard of general farm hygiene are considered to be the most important management tools to control MAP spread within a herd (Djonne, 2010).

2. Test and cull strategies

Complete eradication will require the detection and isolation of infected animals and their off-spring, as these potentially can become infectious at some point in time. “Isolation” in this regard means that infected animals and their excretions should not be allowed contact with susceptible animals.

Control of the infection can be obtained via effective and repeated testing and culling of infectious animals, this will therefore remove the risk of transmission from these animals. Culling of clinical cases is particularly important to managing environmental contamination (Windsor, 2015).

Generally, age can be an indicator of the stage of infection, in that young animals will rarely be expected to shed detectable amounts of bacteria and have IgG1, whereas older animals are more likely to have bacterial shedding, antibodies and clinical disease.

It is important that farmers understand that negative tests do not always ensure zero infection, and that multiple tests need to be undertaken intermittently over a prolonged period of time to obtain the true infection status of the herd (Animal Health Australia).

3. Vaccination against Johne’s Disease

There is a Johnes Disease vaccine (Gudair ®) licenced for use in goats (and sheep), that can be administered to young neonatal kids. It has been used very effectively in the UK (Harwood, 2006) to reduce the level of infection on a farm. It is an inactivated bacterial vaccine, indicated for a single use and administered subcutaneously. As a vaccination schedule at risk herds, Gudair® is recommended for use in all replacement animals between 4 weeks and 6 months of age. In affected herds, the vaccination should be carried out on all individuals including adult animals.

In animals vaccinated with Gudair ® there is a hypersensitivity reaction against other Mycobacterium, (more so in M. avium more than M. bovis), therefore any tuberculin skin test performed for tuberculosis (TB) diagnosis must be carefully interpreted in Gudair ® vaccinated animals. To learn more click here.

Treating Johne’s Disease in Goats

There is no treatment for Johne ’s disease in goats.

Johne’s Disease and Welfare in Goats

In a commercial setting, infected goats with clinical signs should be culled on welfare grounds before the condition worsens.

Good kidding management is crucial on affected farms. Farmers should isolate kids from infected does, and avoid feeding pooled colostrum which could be contaminated with MAP.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

- Maintaining a closed herd will prevent Johne’s disease entering your herd

- Use laboratory blood or faecal examinations to identify infected goats. Remove and isolate these animals immediately, before they can infect susceptible animals

- Identify off spring from infected animals and cull (many will be infected from contact with their dams when suckling)

- Consider snatching kids from does to minimise transmission

- Avoid the use of pooled colostrum from animals with unknown infection status

- Seek advice from your farm vet and implement a vaccination strategy

- Ensure good farm hygiene standards

American English

American English

Comments are closed.