Cattle Diseases

Calf Diarrhoea

Also known as: Scours

Calf diarrhoea, also known as scours, is a condition that can be caused by many different factors that can have serious financial and animal welfare implications in both dairy and beef suckler herds. It has been estimated that 50% of calf mortality in dairy herds is caused by acute diarrhoea in the pre-weaning period (Aldridge and Potter, 2011). Diarrhoea is one the most common diseases reported in calves up to 3 months old (Svensson et al., 2003).

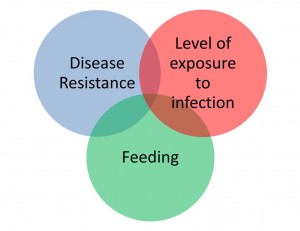

The most important non-specific risk factors for calf diarrhoea are linked to disease resistance, level of exposure to infection and feeding.

1. Disease resistance

The calf is born with an immature immune system. For protection against any infection or challenge from the environment a new-born calf is dependent on the ingestion of adequate amounts of good quality colostrum, which will contain maternal antibodies during the first 24 hours of its life. This is known as passive immunity.

Epidemiological studies have shown that many calves do not acquire enough antibodies during the first hours of life (Besser et al., 1991). This fact is probably the greatest risk factor for calf diarrhoea during the first weeks of life. The main reasons for poor transfer of passive immunity from dam to calf are link to low levels of antibodies in the dam’s milk, because:

- The dam has not been dry long enough without calving (minimum 4 weeks)

- The dam is young (first and second parity cows have significantly fewer antibodies in their colostrum than higher parity cows)

- Inadequate colostrum ingestion – A study by Norheim and Simensen (1985) reported up to 42% of calves left with their dams for 24 hours failed to suckle adequate amounts of colostrum. The reasons are highlighted in the table below:

Inadequate colostrum ingestion can be attributed to the cow or the calf. The tables on the right highlight different factors for both

| Calf Factors |

|---|

|

| Dam Factors |

|---|

|

- Inadequate antibody absorption from the calf’s gut – due to colostrum of insufficient quality or amount being ingested, or due to it being ingested too late. Twenty-four hours after birth no absorption of the antibodies occurs from the gut, but the reduction of antibody absorption is gradual and starts at 2 hours after birth

- There are seasonal differences in the absorption of antibodies (calves born during the summer months in temperate/cold climates achieve higher levels of serum antibodies than calves born during the winter months)

- There are breed differenced: Holstein cows produce poorer quality colostrum and calves are less able to absorb antibodies through the gut than Jerseys

- It has recently been shown that colostrum pasteurisation (which is used to reduce diseases such as Johne’s disease), increases the uptake of antibodies significantly (Gelsinger et al., 2014)

Click here to skip to Maintaining Disease Resistance

2. Exposure to infection

Due to its immature immune system, a newborn calf is vulnerable to infection. The main risk factors increasing the exposure to infection and further lowering the defence mechanism within the calf in early life are:

- Poor hygiene and overcrowding in the calving facility

- Poor hygiene, poor feeding hygiene and overcrowding in the calf pens

- High relative humidity (linked to overcrowding and poor ventilation)

- Low temperature of the incoming air

- Contamination of the incoming air

- Inadequate ventilation

- Close proximity to adult cows

- Mixing of different age groups

- Poor stockmanship/motivation of the herdsperson responsible for the calves

(Cockram and Rowan, 1989; Lance et al., 1992; Radostits and Acres, 1980).

Calf diarrhoea and infectious agents

Whilst infectious agents are important factors in the development of calf diarrhoea, many of them (e.g. corona- and rotavirus and Cryptosporidium) are often present in healthy animals and their environment without causing overt disease. Other infectious agents (e.g. enterotoxigenic E. coli, Salmonella spp.) are usually absent but, when introduced to the environment, tend to cause an outbreak of diarrhoea. In the case of scours caused by digestive disorders, the infectious agents have no role at all.

Most cases of calf diarrhoea are likely to be mixed infections, where more than one of the pathogenic agents is present. Experimental work suggests that infection with one agent makes the calf more vulnerable to other pathogens. Rotavirus is the most common single cause of calf diarrhoea in all types of cattle herds, but particularly in dairy and single-suckler herds. Cryptosporidium is the second most common pathogen causing calf diarrhoea, and slightly more common in beef suckler units than in dairy herds. Coronavirus is the third most common diarrhoea agent. Salmonella is isolated fairly often from disease outbreaks, particularly S. dublin in calf rearing units where calves are bought in from multiple sources (Hall et al., 1988; Reynolds et al., 1986; Snodgrass et al., 1986) .

Links to specific types of calf diarrhoea caused by infectious pathogens:

Click here to skip to Reducing Exposure to Infection

3. Feeding

Scours caused by digestive disorders in calves are common in artificially fed calves. Irregular feeding, changes in the temperature of the milk replacer or whole milk and stressed calves are all risk factors for this type of calf diarrhoea. Incorrect positioning of buckets or artificial teats can also cause digestive disorders, leading to diarrhoea.

Milk replacers are often associated with particular digestive problems in young calves, and their use in high welfare systems should be in emergency situations. Feeding whole milk is the preferred option.

Suckled calves are least likely to suffer from digestive disorders. Changes in the diet or pasture of the dam may result in sudden changes in the milk composition, causing diarrhoea in the calf. “Milky” cross-bred suckler cows and dairy cows used in single-suckler units can also cause diarrhoea in the calf, as a consequence of over consuming on a generous milk supply, particularly if transferred to a “milky” dam from a more restricted diet. These ‘digestive scours’ are usually harmless while on the other hand underfeeding of milk or milk replacer can cause severe long term problems.

Click here to skip to Good Feeding Practices

Control and Prevention of Calf Diarrhoea

Determining the cause of a scour outbreak is important as it may indicate future lines of prevention and may show any potential zoonotic risks, as several organisms causing scour have the potential to cause severe diseases in humans, mainly cryptosporidium and Salmonella. However, this can be difficult as many cases are multifactorial, therefore a thorough investigation should include a study of dry cow management and calving practice as well as calf management (Andrews, 2004a; Bazeley, 2003). Whilst it is important to identify the infectious agents in outbreaks of calf diarrhoea on a farm basis in order to target prevention and control of this disease complex (see the specific types of calf diarrhoea), there are some common approaches to husbandry and management that are likely to reduce the incidence of calf scours, independent of the causative factors. These approaches can be divided into three areas:

1. Maintenance of disease resistance

Calves need adequate amounts of colostrum containing sufficient levels of antibodies. There is research both in support of and against calves being left to nurse on their own or to be tube or bottle fed.

In order to provide the calf with a passive immune protection before its own immune system is fully functional, the calf needs to receive adequate amounts of colostrum containing sufficient antibodies. An amount of 3-4 litres of colostrum that contains 50-150 g/litre of immunoglobulin IgG within the first 6 hours of life has been recommended (Besser et al., 1991). Commercial test kits are available (Colostrometer or Brix refractometer) to estimate the concentration of antibody in a colostrum sample.

Studies have shown that bottle feeding of colostrum provides higher levels of antibodies in the serum of the calf compared to allowing calves to suckle on their own (Besser et al., 1991). On the other hand, it has been shown that calves that are allowed to suckle the dam have an increased rate of absorption of antibodies from the gut (Edwards et al., 1982). The problem with suckling is the obvious uncertainty about the level consumed. A high percentage of dairy calves left to feed on the dam absorb insufficient colostrum levels, as the amount is inadequate to compensate for the poorer quality. A US study that measured the levels of serum antibodies (IgG) in calves to determine the management factors associated with the failure of transfer of maternal antibodies from colostrum. They reported that nursed calves that were more than twice as likely to absorb insufficient antibodies than tube or bottle fed calves (Beam et al., 2009).

First and second parity cows have significantly lower levels of antibodies in their colostrum than higher parity cows. Cows that have a dry period of less than four weeks produce colostrum with low antibody levels (Logan et al., 1981). Freezing colostrum in individual bags or containers from a number of animals of a higher parity may help to provide a “colostrum bank” for a farm in order to supplement those calves deemed to have an insufficient supply of colostrum. Additionally, calves can be further protected by continuing colostrum feeding up to 30 days of age as colostral antibody can have a local protective effect in the gut during this time (Andrews, 2004b). However, pooling of colostrum and milk carries a potential risk of spreading Johne’s disease within a herd.

Whilst the acquisition of passive immunity from the colostrum during the first 24 hours of life is the most important factor in the maintenance of disease resistance in the early days of a calf’s life, the protection provided by continuous ingestion of colostrum during the first weeks can also be protective against diarrhoea. The unabsorbed antibodies in the calf’s gut are, in fact, the only protection against rota- and coronavirus diarrhoea.

In order to increase specific antibodies in the colostrum, the dam can be vaccinated against Salmonella, enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), rotavirus and coronavirus 2-12 weeks before calving. The immunisation of dams against ETEC can be a particularly efficient way of solving an on-going E. coli-problem in a herd, whereas the viral vaccines are less efficient. Routine vaccination of dams to prevent calf diarrhoea should be a last resort in sustainable livestock practices and would need a derogation under organic farming conditions. However, vaccination may be used to tackle a specific disease problem in a closed herd and as part of a planned disease control policy, but it should be noted that vaccines are comparatively expensive and their effect depends on good colostrum uptake.

2. Reducing exposure to infection

Studies of dairy herds have indicated that improved environmental management of calving pens and calf housing reduces calf diarrhoea incidence and the extent of outbreaks. Farmers who handle and treat sick calves become a common and potent source of transfer of pathogens from calf to calf (Radostits and Acres, 1980). A system of “all in – all out” calf housing, cleaning, steaming and disinfection of calf housing and calving pens, regular disinfection of utensils and adequate straw were identified as important management factors. Single penning of new-born calves, rehydration therapy and disinfection of pens have also been indicated as control measures that reduce calf mortality, but single penning whilst it may reduce the spread of disease, is not acceptable in many high welfare systems. In a study, calf diarrhoea incidence was reduced from 36% to 11% within a year by the introduction of early colostrum feeding and improved housing hygiene (Cockram and Rowan, 1989; Lance et al., 1992; Reynolds et al., 1986).

Canadian researchers identified the following measures relevant to beef systems, to reduce infection pressure:

- Outdoor calving as opposed to indoor calving

- Low stocking densities in calving paddocks allowing plenty of space at calving

- Removal to clean paddocks two weeks before calving

- Cows should not be wintered and calved on the same ground

- Sheltered and well drained calving paddocks and rotation of feeding and drinking places within the paddocks

- Immediate removal of healthy calves from areas where an outbreak has occurred

3. Good feeding practice

Cow’s whole milk provides all the nutrients the calf needs from birth to weaning when fed in adequate amounts and is seldom associated with digestive problems. Excess colostrum fed to calves will also provide additional local protection against infection in the gut. Artificially fed calves on whole milk diets can suffer from digestive disorders due to incorrect feeding practices. These can be avoided by correct positioning of the buckets or teats, by adequate supervision of feeding, by regular feeding intervals and by good temperature control of the milk at feeding. Whole milk feeding is just as likely as milk replacer feeding to spread infections within the herd if proper hygienic precautions are not taken (Losinger and Heinrichs, 1997).

Treating Calf Diarrhoea

In the case of an outbreak of diarrhoea in a herd, it is important to attempt to diagnose the infective cause of the disease in order to target further control measures appropriately. Dead calves should be sent for examination and faeces samples should be obtained for tests from a minimum of four affected and four normal calves within the affected group. Consultation with the vet is recommended.

Scouring calves need to be isolated from the others; rehydration solutions and provision of clean, dry bedding is required.

Isolation of affected calves, effective treatment with rehydration solutions and provision of dry and warm conditions are vital in the treatment of calf scours. The main aim of treatment is to restore the fluid balance in the animal by rehydration therapy. Oral therapy is the best way of providing rehydration fluids, but this may need to be replaced by intravenous therapy in severe cases where the calf is unable to drink. The use of stomach tubes can be problematic if the fluid is deposited into the rumen and the absorption of the fluid is slow. A return to whole milk feeding is recommended within two days of rehydration therapy to avoid a negative energy balance. (Grove-White, 2004). A regime consisting of normal continuation of milk feeding and additional fluid therapy is advocated by some authors.

Suckled calves should have limited access to the dam or suckler cow until full recovery has been achieved. During this period they should receive regular rehydration therapy.

The use of antibiotics in diarrhoeic calves has been shown to be contraindicated in many studies, due to the further disruption of gut flora, the establishment of carrier states of salmonella-infection and the development of antimicrobial resistance factors in the enteric flora. Although very sick calves with systemic E. coli infection or salmonellosis may benefit from antimicrobial therapy, most studies have also failed to show any beneficial effect of antimicrobial treatment (Buntain and Selman, 1980; Rollin et al., 1986). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) like meloxicam have shown beneficiary effects as they reduce pain and inflammation (Todd et al., 2010)

Homeopathic remedies have not been shown to be effective in field based calf scour infections (de Verdier et al., 2003). They should be used with care on farms and if any doubt exists about a calf’s status, a veterinary surgeon’s advice should be sought.

A recent open access review of prevention and treatment of calf diarrhoea can be found at Meganck et al., 2014.

Calf Diarrhoea and Welfare

Calf diarrhoea is one of the main causes of early deaths in calves, and is a major animal welfare concern in dairy herds. The fact that the majority of scouring problems can be avoided by good management adds to the need to tackle calf diarrhoea problems if they exist in the herd. It is not uncommon for farmers not to isolate sick calves (Howard, 2004) and by not removing a calf from a group, it is likely that others in the group will be at increased risk of contracting the infection.

Isolation of affected calves, effective treatment with rehydration solutions and provision of dry and warm conditions are vital in the treatment of calf scours, in order to avoid further suffering. There is evidence to suggest that the addition of antibiotics to the rehydration solution does not improve recovery. The use of oral antibiotics should be carefully considered in the case of undiagnosed outbreaks of calf scours to avoid further disruption of gut flora. If the calf is incapable of drinking the rehydration solution, parenteral rehydration has to be provided.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

Good practice to control and prevent calf diarrhoea can be divided into four areas of action:

- Maintenance of immune status

- Minimisation of exposure to infectious agents

- Good feeding practice

- Reduction of stress.

1. Maintenance of immune status:

- Provide adequate bedding to allow the calf to stand without difficulty. Ensure early feeding, assist if needed, monitor the intake as closely as possible and record it (“maximum supervision, minimum interference”)

- Keep a supply of frozen colostrum in case the dam leaks colostrum before calving. Fermented whole colostrum can also be used, preferably from dams that have been vaccinated for scour pathogens

- Feed the calves colostrum as long as possible but only from her dam (or one single cow) , to provide passive, “in-gut” protection against viral diarrhoea

- Encourage outdoor calving

- In the case of a specific, identified agent and a continuous problem, immunise pregnant dams before calving as part of a targeted control plan (see specific diarrhoea types).

2. Minimisation of exposure:

- Provide adequate numbers of calving pens and clean and disinfect them between batches

- House calves of different ages in different air spaces or with adequate separation

- Remove dairy calves quickly from the dam and house calves well away from the calving pens

- Avoid overcrowding in calf housing

- Keep up high hygiene standards throughout the calving period and in calf housing

- Disinfect all feeding equipment daily

- Ensure good biosecurity practice to reduce the risk of exposure to disease agents (Barrington et al., 2002)

3. Good feeding practice:

- Feed fresh or fermented colostrum from own dam to all calves for as long as possible. Do not feed mastitis milk or milk with antibiotics to calves

- Use teat buckets or automatic feeders rather than buckets if possible

- Make sure that feeding position is correct

- Feed regularly, the more often the better, and make sure that the milk is not too cold

- Provide constant access to fresh water

- Good quality solid feeds such as good hay should be made available from the first few days of life to encourage a smooth transition to weaning at a later date.

4. Reduction of stress:

- Avoid overcrowding in calf pens

- Avoid wet bedding

- Make sure that calves are well bedded during cold weather and do not suffer from draught

- Provide shelter during prolonged cold and wet conditions on pasture

If the farm has a known and continuous calf diarrhoea problem, contact the vet and make a plan for eradication or improved control – particularly in the case of Salmonella-infection.

If the farm has an undiagnosed continuous calf diarrhoea problem, organise sampling during the next outbreak to identify the causative agent and factors, and make a plan to improve control, as above.

Set up a recording system for individual calf scour cases and outbreaks of scours. Review the records at least twice during the conversion period and assess the situation, particularly after the first calf crop that has received whole milk.

American English

American English

Comments are closed.