Cattle Diseases

Bovine Coccidiosis

Also known as: Eimeria

Bovine coccidiosis almost invariably affects cattle less than one year old (Cornelissen et al., 1995; Daugschies and Najdrowski, 2005), and often follows turnout (Marshall et al., 1998; von Samson-Himmelstjerna et al., 2006). However, older cattle may develop the disease (Gunning and Wessels, 1996). The condition has been reported by some organic farms to be a problem (Höglund et al., 2001).

Coccidiosis is caused by single celled parasites (protozoa) called Eimeria, which undergo a complex life cycle in the gut (See below). Eimeria species have been identified to cause disease in a range of animals (Pigs, poultry and lambs), however they are host specific (i.e., cattle Eimeria spp. cannot infect sheep) and 13 species have been isolated from cattle. Of these, only 3 are regarded as pathogenic; Eimeria zuernii, Eimeria bovis and recently Eimeria alabamensis. E. zuernii and E. bovis are classically associated with disease in housed calves, whereas, E. alabamensis has been reported in both housed and more especially grazed cattle (von Samson-Himmelstjerna et al., 2006). Most Eimeria spp. infections will induce sub-clinical coccidiosis (Cornelissen et al., 1995). Infection of naive calves with large numbers of infective oocysts of E. bovis and E. zuernii, however, may result in severe diarrhoea with faeces containing blood, fibrin and intestinal tissue (Cornelissen et al., 1995).

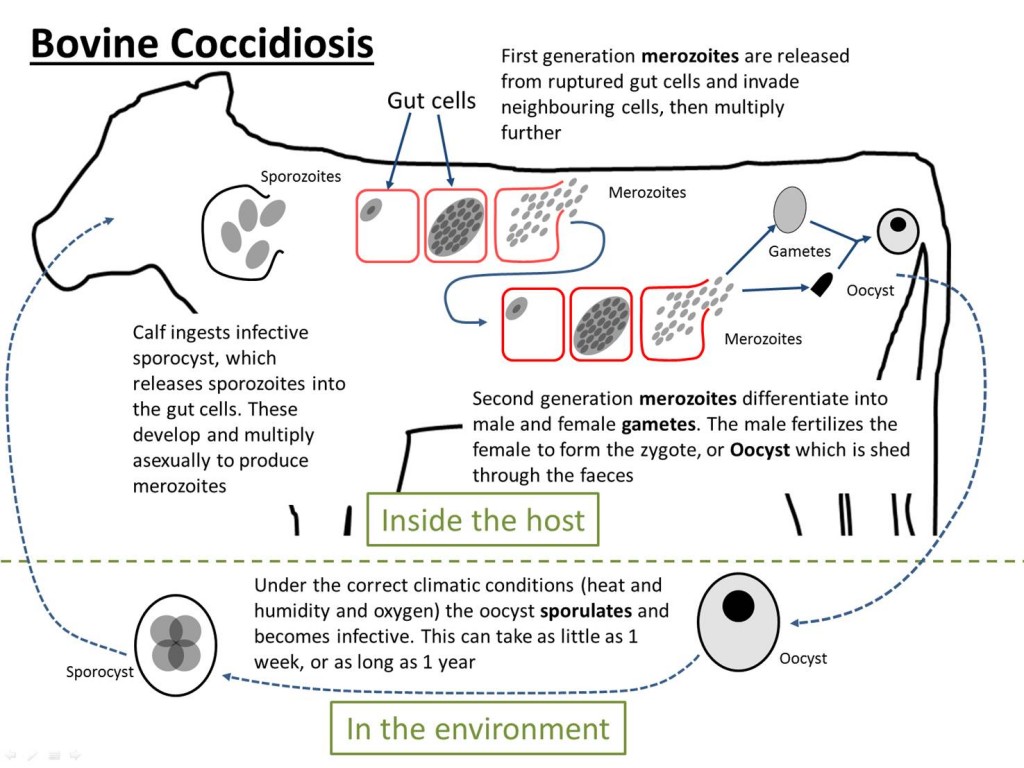

The life cycle of bovine coccidiosis. There is a stage within the host and a stage in the environment. It is a direct lifecycle, meaning that it only requires one host.

The Life Cycle

- Oocysts (protozoan eggs) are shed in the faeces of infected animals. They can survive on the ground for up to a year.

- If a calf swallows some infective oocysts, they break open in the gut and release merozoites, which invade the gut wall.

- Each parasite grows and multiplies by repeated asexual division to produce a hundred or more daughter parasites

- These second generation merozoites rupture the host cell and invade fresh areas of the gut wall and repeat step 3. Within 10-14 days, the parasites will have multiplied by up to a million fold.

- By this stage of infection, parts of the gut wall are packed with parasites which develop into male and female sex cells, or gametes.

- The female sex cells are fertilised and secrete an oocyst wall around them, then drop off the gut wall to be excreted in the faeces, completing the cycle.

The life cycle from ingestion to patency takes 15-17 days for E. zuernii and 15-20 days for E. bovis. Oocyst production during infection with a single species lasts for 5-12 days, but may be prolonged in multiple species infections.

Clinical disease is usually associated with ingestion of large numbers of infective oocysts of pathogenic species and is manifested by enteritis, diarrhoea and, in severe cases, dysentery (bloody and mucous in diarrhoea). The diarrhoea or dysentery is sometimes accompanied by severe straining (tenesmus) that may lead to rectal prolapse. The larger the infective dose, the more severe the clinical signs (Hooshmand-Rad et al., 1994). Infections can occur both indoors, on damp and faeces-contaminated bedding, or outdoors, around drinking and feeding troughs. Low level infections levels will result in the induction of protective immunity. Light infections are self-limiting, but severe infections can be fatal if untreated. Oocysts can be seen in faecal samples using light microscopy. However, oocysts counts can sometimes be unreliable as healthy animals can pass more than 10 million oocysts per gram of faeces, animals can die of coccidosis before any oocysts are shed and oocyst output may be transient – an animal that is dying of coccidiosis may show very few oocysts (Taylor, 2000).

The oocysts are very resistant to external conditions and can survive for up to two years in suitable environments. They require warmth, humidity and oxygen to sporulate (development to infectivity) and can over-winter, but are susceptible to drought, high temperatures and disinfectants (Daugschies and Najdrowski, 2005).

Control and Prevention of Coccidiosis

As infections are initiated by ingestion of oocysts, control strategies must be aimed at reducing the number of oocysts in the environment. Measures to reduce the risk of infection include the removal of food contaminated with faeces and better placement of feeding and water troughs. If possible, creep feeders should be moved at regular intervals to prevent the build-up of infection around them. Also, if possible, calves should be turned-out in the spring to pasture that has not been grazed by calves in the previous year (Svensson, 1995). Also, hay made from pasture with high levels of oocysts can cause severe disease in young stock (Svensson, 1997). If the animals are kept indoors, plenty of fresh bedding should be provided on a regular basis. The lower stocking rate often adopted in pasture based farming systems reduces the risk of build-up of large numbers of oocysts. Areas of shelter should be kept as clean as possible.

There is some evidence that calves develop a strong immunity to E. alabamensis if exposed in their first grazing season and may be able to graze contaminated pastures in their second year without clinical signs, and, as such may act to clean contaminated pastures (Svensson, 2000). However, this should not be relied upon as a control strategy as older animals can still excrete oocysts and contribute to an environmental load (Daugschies and Najdrowski, 2005).

Treating Coccidiosis

Severely affected calves require individual treatment with an anticoccidial on the advice of a veterinarian and, if deemed advisable, fluid therapy with electrolytes and injections of antibiotics to control secondary bacterial infections. Diclazuril (Vecoxan, Janssen Animal Health) and toltrazuril (Baycox, Bayer Animal Health) have been licensed for use in the treatment and control of bovine coccidiosis.

Coccidiostats such as decoquinate (Deccox, Alpharma, Belgium) can be added to animal feeds to help in control of a disease outbreak, but this method of control should only be resorted to in severe cases.

Coccidiosis and Welfare

A continuous coccidiosis-problem on a farm is of welfare concern and an indication of poor hygiene standards. If treatment is routinely needed for clinical coccidiosis on-farm, the animal husbandry and hygiene situation should be reviewed.

Treatment should not be withheld from a clinically affected animal as the condition is distressing and can be fatal.

Good Practice based on Current Knowledge

- Maintain low stocking rates both in housing and on pasture

- Remove food contaminated with faeces

- Ensure good placement of feeding and water troughs

- Move creep feeders at regular intervals

- If the animals are kept indoors, provide plenty of fresh bedding

- Keep areas of shelter as clean as possible

- Do not turn-out calves in the spring to pasture that has been grazed by calves in the previous year

- Do not feed young cattle hay made from pasture with high levels of oocysts

- Treat severely affected animals with an anticoccidialon the advice of a vet

- If necessary, give fluid therapy with electrolytes

American English

American English

Comments are closed.