Cattle Diseases

Mange in Cattle

Also known as: Allergic Dermatitis, Dermatitis

Mange is the collective name for allergic dermatitis caused by the infestation of mites.

These obligate ectoparasite are transmitted mainly by direct animal to animal contact, although they can survive for about two weeks in the environment like posts. Mange presents as a skin condition associated with irritation and scratching that leads to inflammation, exudation with crusts and scabs forming on the skin. Untreated mange leads to thickening of the skin and loss of condition of the animal. Mange is often seen in animals during the winter season. Mange can be a big welfare issue in dairy herds if the treatment of lactating animals is withheld.

Most infections are limited by the animal grooming itself when husbandry conditions allow this and do not jeopardise animals’ natural resistance to the disease.

Mange and Welfare

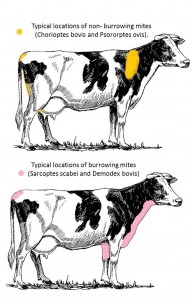

There are two types of mange mites:

- Burrowing (Sarcoptes scabei and Demodex bovis)

- Non-burrowing mites (Chorioptes bovis and Psoroptes ovis)

In the Northern Hemisphere, chorioptic mange is currently considered to the most common form of mange. It is generally milder than that caused by the Sarcoptes and Psoroptes mites, as the Chorioptes mites live on the skin surface rather than burrowing into the skin. The condition is normally seen in adult confined cattle, particularly in winter, and is not necessarily indicative of poor management. It can cause restlessness and reduced well-being (Rehbein et al., 2005).

Sarcoptic mange is rare. The mite causing psoroptic mange is related to sheep scab, but it is unclear whether it is transmissible from sheep to cattle.

The different responses of different mites to various treatments underlines the importance of diagnosing the species.

The burrowing mite, has a life cycle of about three weeks from egg to adult, after which the adult female will lay eggs for up to 60 days. The most common sites for sarcoptic mange on cattle are inner thigh, underside of neck and brisket and around the root of the tail. Small areas of infestation do not cause major irritation to the animal, but a generalised condition can be extremely distressing.

The non-burrowing mites, Chorioptes and Psoroptes, have a similar life-cycle to the burrowing mites, with a slightly shorter adult phase of 40 days. The preferred site for Chorioptic mites is at the base of the tail, in the perineum and, in winter, at the back of the udder. Long-haired, highland cattle are considered to be particularly susceptible to infection. Psoroptic mites are initially found on the withers, with the condition rapidly worsening to exudative dermatitis, associated with severe irritation.

Whilst dairy cattle are generally less susceptible than beef animals (Bates, 1998), all cattle are less susceptible to mange than sheep, as grooming is more efficient in cattle and acquired infections are usually eliminated by the animal.

As clinical mange is a distressing condition, all affected animals should be treated immediately with an efficacious preparation and further infections should be prevented effectively.

Most infections are limited by grooming by the animal itself if husbandry conditions allow this and do not jeopardise animals’ natural resistance to the disease. High prevalence of advanced cases of mange affected animals in a cattle herd is usually a sign of extremely poor husbandry and/or other concurrent illnesses/conditions.

Control and Prevention of Mange

Maintaining condition in cattle throughout winter and thorough control of other illnesses is the best way to prevent mange in cattle. Closed herd policy, quarantine and treatment of bought-in animals and avoidance of communal grazing prevent the disease from entering a herd.

When cattle rub and scratch against posts and walls, it can not only damage buildings, but it also leaves a trail of mite eggs. These eggs can survive for three to four weeks and therefore can be picked up by a passing animal at a later date. Ensuring a clean housed environment will limit the risk of spread. C. bovis mites can survive on a various surfaces, including glass, rubber, metal and plastic, for more than 2 months and given that the mite can survive on and off the host, it is particularly difficult to eradicate and unless treatment is synchronised, re-contamination and persistence will occur (Villarroel and Halliburton, 2013).

The process of self-healing can be significantly slowed by the continuing presence of mites within the housed environment.

Mange control in conventional herds has been achieved as a side product of internal parasite control, particularly with systemic use of macrocyclic lactones. In infected herds, elimination of infection and subsequent preventive strategy should be the main aim of a control policy.

Treating Mange

Mange can be controlled by the use of injectable and pour-on products.

Treatment of mange in conventional cattle herds is achieved efficiently with macrocyclic lactones (avermectins and milbemycins) and synthetic pyrethroids.

Macrocyclic Lactones Pour-on application of moxidectin can be used in beef and -dairy animals. The conventional milk withdrawal times are currently zero in the USA and Canada and 6 days in the UK., and in the past has been found effective against psoroptic mange (Losson and Lonneux, 1996). However, a recent re-introduction of psoroptic mange in the UK appeared to be unresponsive to both routinely used macrocyclic lactones and synthetic pyrethroids. Eprinomectin is an avermectin licensed for lactating dairy cows, with a zero milk withdrawal period in conventional systems and although Eprinomectin has been found to be very effective against Chorioptic mange (Barth et al., 1997; Rehbein et al., 2005), it does not carry a datasheet claim of efficacy against Psoroptes. Although Chorioptic mange can be controlled in entire herds with eprinomection, multiple treatments may be required to eradicate the parasite (Villarroel and Halliburton, 2013). Under dosing should always be avoided and discouraged, not least as it creates an environment for te development of drug resistance.

Recently, the efficacy of long-acting ivermectin injection was tested and resulted in all cattle becoming free from Sarcoptes mites within 14 days post-treatment and 13 or 28 days in the Psoroptes studies (Hamel et al., 2015). This option however is not applicable to dairy animals and the wide spread use of invermectin has been reported to have important environmental consequences for pastureland associated with its insecticidal actions on beneficial dung beetles (Wall and Strong, 1987).

Certain precautions should be taken into consideration when using macrocyclic lactone preparations. Moxidectin in either topical or injectable form is a macrocyclic lactone, strictly not anavermectin, less environmentally damaging than avermectins and no significant effects on the dung fauna were observed (Strong and Wall 1994). They are not suitable for calves under 8 weeks of age although the pour on can be given to lactating cattle (see above). They are also effective against the developmental stages of lice. Eprinomectin in topical form is licensed for lactating dairy cows with a zero milk withdrawal period and a 15 or 10 days meat withdrawal.

Synthetic Pyrethroids Permethrine is a synthetic pyrethroid licenced to treat chorioptic and sarcoptic mange. When using synthetic pyrethroids, a re-application is required (after four weeks for permethine). Also be aware of the environmental issues – synthetic pyrethroids are very toxic for aquatic life. More can be found on at NPIC website.

A herbal compound, Charmil (containing deodar and karanga oils, marketed in India by Dabur Ayurvet Ltd.), has been found to be efficient against sarcoptic mange in cattle and buffalo (Singh and Gill, 1993). It is not licensed for use in all countries.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

More detailed information on the control of mites and ectoparasites can be found at the COWS website

- Keep animals well-nourished and in good condition, especially during the winter months

- Maintain a closed herd policy

- Quarantine and health check bought-in animals

- Investigate and treat immediately any skin conditions that cause irritation and scratching

- If mange is diagnosed, treat immediately and ensure that the infection has been eliminated from the herd

- Speak to your neighbours and those who graze their animals communally with yours

- If communal grazing is unavoidable, joint efforts to control the disease with other communal grazing users should be attempted. If this fails, regular checking of the animals for signs of mange and treatment before introduction back to the farm should be carried out

- Care should be taken when using parasitides to ensure correct use in order to reduce the risk of parasitide resistance

American English

American English

Comments are closed.