Cattle Diseases

Ringworm in Cattle

Also known as: Dermatophytosis

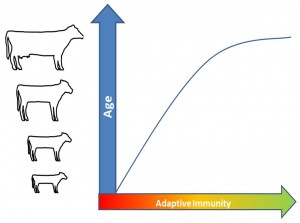

Ringworm is a fungal infection of the keratin in the skin and hair. Cattle and sheep are commonly affected, but other species, including man and horse, can be infected. Thus, ringworm is a potential zoonotic disease. Clinical signs are often seen in the winter during the housed period. Circular lesions are characteristically grey-white, with a powdery surface and scant hairs. Lesions can be slightly raised and swollen, particularly around the edges. Severe lesions can become thickened with scales and leave raw, bleeding surface when the scaly lesion is removed. The lesions do not normally cause irritation or generalised symptoms in affected animals. In cattle, the infection is most commonly seen in calves and young stock, where the lesions are mainly seen around the eyes, on the ears and on the back. The lesions are less rare in adult cattle and are seen when infection is introduced into a naïve herd, for example by purchase of new stock. Additionally, because immunity is not long-lived, adults can develop clinical signs if exposed to a heavy challenge from youngstock.

Ringworm is a fungal infection of the keratin in the skin and hair. Cattle and sheep are commonly affected, but other species, including man and horse, can be infected. Thus, ringworm is a potential zoonotic disease. Clinical signs are often seen in the winter during the housed period. Circular lesions are characteristically grey-white, with a powdery surface and scant hairs. Lesions can be slightly raised and swollen, particularly around the edges. Severe lesions can become thickened with scales and leave raw, bleeding surface when the scaly lesion is removed. The lesions do not normally cause irritation or generalised symptoms in affected animals. In cattle, the infection is most commonly seen in calves and young stock, where the lesions are mainly seen around the eyes, on the ears and on the back. The lesions are less rare in adult cattle and are seen when infection is introduced into a naïve herd, for example by purchase of new stock. Additionally, because immunity is not long-lived, adults can develop clinical signs if exposed to a heavy challenge from youngstock.

There is very little information on immunity to ringworm infection, but re-infection after natural infection appears to be rare. The spores of ringworm fungi can remain infectious in the farm environment for months, if not years. New infections can be brought in by wild animals, bought-in stock which are incubating the disease or animals returning from livestock shows. The incubation period is between one and four weeks.

Control and Prevention of Ringworm

Ringworm is common throughout the world. Some European countries have statutory or voluntary control policies for the disease (Forshell and Gyllensvan, 1991; Gudding et al., 1991). In spite of its zoonotic nature, the disease is not notifiable in the UK.

Organic beef farmers have indicated that ringworm is one of the main health problems in young stock (Roderick and Hovi, 1999).

As the disease is particularly common in young stock during the housing period and in crowded conditions, control should focus on providing good housing conditions, disinfection and cleaning of the premises during the grazing season and immediate isolation and treatment of affected animals. Phenolic disinfectants or sodium hypochlorite are recommended for disinfection of buildings and grooming and feeding utensils. Buildings can also be sprayed with caustic soda (1% solution). Formaldehyde is not recommended on pasture based farming systems.

Where there is a serious herd problem or eradication of ringworm from a herd is attempted, vaccination can be used as part of a herd health plan. Vaccines are considered effective and cost-beneficial, and provide protection for up to one year (Gudding et al., 1991; Rybnikar et al., 1991). Disinfection of premises is particularly recommended to improve the effectiveness of a vaccine-based control programme (Gordon and Bond, 1996).

A vaccine is available against ringworm. A list of medicines available in the UK can be found on the National Office of Animal Health (NOAH) website.

Treatment of Ringworm

Ringworm in calves often clears up when they are turned out in spring partly due to improved nutrition.

Animals often self-cure following turn-out in the spring, with many cases not requiring specific treatment. Treatment of ringworm with topical anti-fungal preparations has been used widely and provides reasonable cure rates (Rhaymah, 1999; Andrews and Edwardson, 1986).

Thiabendazole has been indicated to have efficacy in ringworm treatment and may be considered (Guth, 1988), however, it is important to remember that this is primarily an anthelmintic drug and additional use should be limited in order to prevent anthelmintic resistance. Topical, herbal remedies have been shown to be as efficacious as anti-fungal agents (Sharma and Dwivedi, 1990; Sharma et al., 1993; Bosoglu et al., 1998, Clark et al., 1990, Cam et al., 2009). Vaccination as therapy has also been shown to enhance cure in affected animals (Bredahl and Andersen, 1998). Thomsen and Fougt (1984) report the efficacy of selenium and vitamin E injections in curing ringworm infections in cattle. Similarly, vitamin A is recommended as a support therapy to assist recovery.

The treatment of ringworm should be combined with disinfection of buildings (see Prevention and Control).

Ringworm and Welfare

Ringworm is not usually considered a welfare problem as the lesions do not cause serious irritation. It is, however, recommended that endemic ringworm infections are treated and control measures are implemented to prevent serious lesions from developing.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

If ringworm is a continuous problem on the farm:

- Implement a closed herd policy

- Include a ringworm reduction plan in the animal health plan

- Consider vaccinating all young stock and treating all affected animals at turnout (plan phasing out of vaccination once clinical incidence disappears)

- Disinfect all buildings and utensils (see Prevention and Control), and burn or thoroughly compost all bedding

- During the following housing period, isolate and treat all affected animals immediately at diagnosis

- Repeat vaccination and disinfection at next turnout

If ringworm is not a problem on the farm:

- Implement a closed herd policy.

- Check the health status of herd of origin regarding ringworm if you consider buying animals

- Quarantine all bought-in animals for a minimum of two weeks

American English

American English

Comments are closed.