Goat Diseases

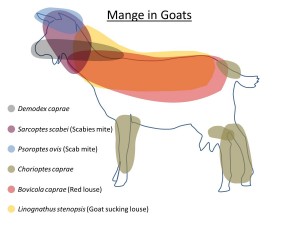

Mange in Goats

Mange is essentially a severe dermatitis caused by an infestation of either mites or lice. Both mites and lice are ectoparasites that inhabit the skin where they feed on skin debris, subcutaneous secretions, blood or lymph. Some will puncture the skin to feed, and others scavenge from the skins surface. Infestation with mites is known as acariasis, and infestation with lice is known as pediculosis.

Typical clinical signs of mange include restlessness, intense scratching, rubbing, coat damage, exhaustion, poor growth rates and skin damage. Severe cases of mange are a significant welfare concern and can cause severe economic losses. A summary of the common mites and lice that cause mange in goats, the location on the body and the clinical signs of infestation can be found below. The details have been extracted from Taylor, Coop and Wall, 2007.

| Ectoparasite (Common name) |

Description | Location on goat | Clinical signs | Geographical distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bovicola caprae or Damalinea caprae (Red louse) |

Chewing louse up to 3mm long | Back and upper parts of the body | Restlessness, rubbing, coat damage, exhaustion, poor growth rates and skin damage. Wounds may attract blowflies ((LINK)). | Worldwide |

| Linognathus stenopsis (Goat sucking louse) | Sucking louse, up to 2mm long with a pointed head. They don’t have eyes. | Head, neck and back | Infested animals stamp their feet and bite the infected areas causing skin damage. | Worldwide |

| Chorioptes caprae (also known as Chorioptes ovis, Chorioptes equi, Chorioptes bovis and Chorioptes cuniculi) | It is a non-borrowing mite. Adult female is about 300µm in length. The same chewing mite can infect cattle, sheep, rabbits horses and goats. | Skin, particularly the legs and fore feet, but also the base of the tail and upper rear surface of the udder | Infected animals may stamp or scratch infected areas causing skin damage. | Worldwide |

| Sarcoptes scabei (Scabies) | A borrowing mite, about 0.75mm in length. This is a zoonotic parasite that also can infect sheep, cattle, horses, rabbits, camelids and goats | Usually starts on the head and ears then moves to the body. | Infection is intensively itchy and often chronic. The main signs are encrusted lesions, hair loss, abrasions from rubbing and scratching. Exhaustion and poor growth rates. | Worldwide but of most economic importance in India and West Africa |

| Psoroptes cuniculi (Scab mite also known as Psoroptes ovis and Psoroptes equi)These mites can survive off host for up to 18 days! |

Non-borrowing mite about 0.75mm in length. The eggs are large (250µm) and oval. They feed superficially on lipid emulsion of skin cells, bacteria and lymph of host skin produced as a result of a hypersensitivity reaction to the mites faeces* | Ears – causes crusting in the ears leading to head shaking.

Primarily a winter disease |

As the lesions grow the centre becomes dry and covered in a yellow crust, whilst the border (where the mites are feeding) become moist. Animals become so preoccupied in scratching due to the intense itching, they become restless, exhaustion, and often suffer from weight loss and poor growth rates | Worldwide particularly Europe and South America, but not Australia and New Zealand |

| Demodex caprae | Host-specific small cone-shaped mite which causes demodectic mange in goats occurs most commonly in kids, pregnant does, and dairy goats. The nodules contain a thick, waxy, grayish material that can be easily expressed; mites can be found in this exudate (MSD Animal Health) | Initial lesions on the face and neck extend to the chest and flanks and may eventually spread all over the whole body.

These mites cannot live off the host and are highly host-specific. |

For a definitive diagnosis a deep scraping is required to reach the mites deep in the follicles. Transmission requires prolonged contact such as when suckling, hence most infections are acquired in the early weeks of life and seen on the muzzle, neck and withers. | Worldwide |

*Surrounding the mite’s faecal pellets is a cuticle containing enzymes which induce a strong inflammatory response by the hosts.

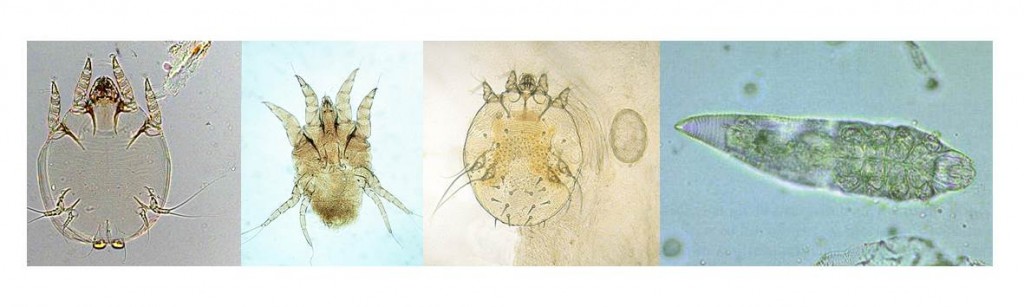

Mites

Mange mites in order from left to right; typical adult female Chorioptes spp. mite (source www.upei.ca), Psoroptes cuniculi spp. (image from www.wikiedia.com), Sarcoptes scabei (from www.cerimes.fr ), Demodex caprae (from www.leine.no). These images are not to any relative scale.

Mites are obligate parasites in that require a host to survive. They can be grouped as either borrowing ( e.g., Sarcoptes scabiei) or non-borrowing (e.g., Psoroptes and Chorioptes) depending on their feeding behaviour. Most mites spend their entire life in close contact with the skin of its hosts, so transmission is primarily via direct physical contact from animal to animal. However some mites (e.g., Psoroptes and Chorioptes) are able to survive off the host for prolonged periods (about 2 – 3 weeks, and up to 2 months, respectively). The survival time off hosts is determined by climate as in hot, dry (low humidity) climate mites will suffer high mortality rates. Nevertheless there is a chance that animals can pick up an infestation from the environment so this must be considered when planning quarantine and treatment. The general life-cycle of mites is outlined on the left. During the nymph stages, the mite will not feed – this is important as the scab mites will not be ingesting any treatment , hence the need for at least two injections for non-persistent products.

Mite infestation can be associated with poor health of the host and in temperate climates commonly occurs at the end of winter or in early spring.

Lice

Lice generally spend their whole life-cycle on the host and will only leave to transfer to another host. They can survive 1- 2 days off host but will tend to spend their entire life-cycle on a single animal. Lice are often host-specific, some even favouring particular anatomical areas. Lice can range from about 0.5mm – 8mm in length, wingless and can be described as either chewing lice or sucking lice depending on their feeding habits.

*Both images below are from ces.cisro.au

Chewing lice

Chewing lice such as this ‘Red louse’ are usually about 2-3mm in length, often have large round heads (in relation to their bodies). They have distinct chewing mouthparts and usually feed on fragments of hair or skin, and in goats include the species Bovicola caprae or Damalinea caprae also known as the Red louse.

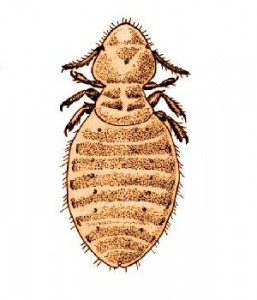

Sucking lice

Sucking lice such as this ‘Goat sucking louse’ usually have small heads (relative to body size) and have mouthparts specifically adapted to piercing skin so they can suck blood. Severe infestation with sucking lice may cause anaemia.

A small number of lice may present minimal disturbance to the host, in fact some lice can be considered part of the normal fauna. However louse populations can increase very rapidly and reach incredibly high densities. In these cases animals will become restless, they will scratch and probably self-wound. The irritation will be distracting and can cause weight-loss and poor growth weights. Heavy infections are more commonly seen in young animals or those in poor health.

Control and Prevention of Mange in Goats

The major risk factors for introduction mange into your goat herd are:

- Buying in goats

- Neighbours stock

- Other animals on the farm

- Common grazing

A closed herd policy, quarantine, inspection and possible treatment of bought-in animals should prevent mange from establishing on your farm, however this is not full proof as neighbouring stock also pose a risk, therefore the avoidance of communal grazing to prevent the disease from entering your herd and good maintenance of your farm boundaries to minimise contact with neighbouring stock is also advisable.

Treatment of Mange in Goats

There are different options for treating mange in goats, but the choice of product will depend on the cause (e.g., lice or mite) and severity of infestation, the system (meat or milk) and age of the animals. A correct diagnosis is required as some products do not treat lice, and some require a booster dose in order to be fully effective. Additionally incorrect or over-reliance of treatments has implications for the inadvertence selection of drug resistance. Your local farm vet should be able to advise on the best course of treatment.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

If your herd is free from mange, keeping mange off the farm is your first priority. This can be achieved by careful quarantine and inspection of new or returning stock and by maintaining your farm boundaries to minimise contact with neighbouring stock. Additionally,

- On common grazing land – an agreement needs to be made with others to agree a treatment and control plan

- When buying in stock treat for mange on arrival

- New stock should be kept in quarantine from the herd for at least 4 weeks

- Goats arriving on the farm should be treated e.g. returning from shows or sales

- Lorries and trailers can harbour the disease and should be thoroughly cleaned after use

- Ensure all contractors clean and disinfect equipment (handling systems, shearing equipment and scanners) before handling your animals

American English

American English

Comments are closed.