Goat Diseases

Mastitis in Goats

Also known as Udder inflammation

Early signs of mastitis include a drop in milk yield, modified milk texture, colour, smell and/or taste, lameness, and / or misshapen udders.

Small ruminant bacterial mastitis is often, but not only chronic and contagious, with infection spreading mainly during milking (Bergonier et al., 2003 ).

The pathogens causing mastitis in goats

Clinical Mastitis

Several pathogens can infect the goat udder, but the most severe is mastitis caused by S. aureus. Although sporadic, clinical mastitis caused by S. aureus may result in gangrenous mastitis, characterised by necrotic udder tissue which will eventually cause the udder to fall off, and the animal will die. The severity and painfulness of this disease makes S. aureus-mastitis a threat to animal welfare.

S. aureus has also been detected in many sub-clinical cases, and it is not yet clear how these relate to clinical cases.

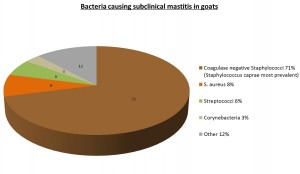

Sub-clinical Mastitis (SCM)

In goats, coagulase-negative Staphylococci (CNS; which is made up of many different species of bacteria) are responsible for most cases of sub-clinical mastitis. Sub-clinical mastitis is characterized by reduced milk production, increased somatic cells and bacterial presence in the milk, but it lacks the macroscopic changes typical of the clinical stage.

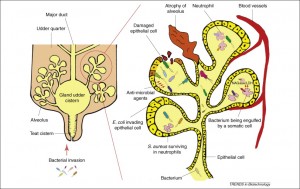

Mastitis occurs when bacteria invades the udder. Good milking hygiene, and good maintenance of the machinery are important in minimising the amount of bacteria in the parlour and reduce the transmission of pathogens from infected to uninfected udders.

Teat damage

Mastitis develops when bacteria gain access to the udder, via the teat canal (see image above). The teat end can be damaged as a result of over milking, a poorly maintained milking machinery, rough removal of the clusters, getting teats caught on brambles or wire or as a result of teat biting. Teat-end damage allows bacteria to enter the teat canal, and can lead to mastitis.

Viral mastitis

In goats there is a virus that particularly targets the udder, a lentivirus or caprine arthritis encephalitis virus, CAEV. Clinical cases are known as ‘hard udder’. The acute form of this viral mastitis appears at parturition as a very firm udder, but the overlying skin is loose and free from swelling, and most importantly milk flow is almost absent (Koop et al., 2012). Dairy goats that are seropositive for CAEV, and have a negative bacterial culture can still have an increased Somatic Cell Count (See below) (Sánchez et al., 2001). Learn more about CEAV here ).

Somatic Cell Count

Somatic cell counts (SCC) is a count of the number of body cells in a quantity of milk expressed as cells/mL, and can be measured at either the gland level (the udder), individual animal level, or herd level (bulk milk SCC) (Koop et al., 2012).

SCCs consist mainly of immune cells (leukocytes) that enter the milk compartment of the udder. There are always small quantities of immune cells in the milk, and their function is to protect the udder against infection by bacteria. Usually, the older the animal gets, the more somatic cells it tends to have in its milk. In dairy cows a relationship between SCC and mammary infections has long been demonstrated, and therefore, SCC are widely used to identify cows likely to have an intra-mammary infection. Most milk processing companies with use bulk milk somatic cell count (BMSCC) to estimate herd mastitis prevalence (Madouasse et al., 2010). However this relationship is a lot more complex in goats.

In goats the relationship between SCC and number of presumed persistently infected does is much harder to define because SCC seems to be affected by infectious and non-infectious factors. (Koop et al., 2012). Several studies have shown that non-infectious factors also influence SCC in goats such as stage of lactation, e.g., the higher the SCC the later the stage of lactation (Gomes et al., 2006; Koop et al., 2011; Olechnowicz and Sobek, 2008), parity (Luengo et al., 2004; Wilson et al., 1995) oestrus (Moroni et al., 2007) and breed (Paape et al., 2007).

A high SCC in goats is not always accompanied with a positive bacterial culture (Koop et al., 2012). Simply put, the SCC threshold in goats is much higher. Because of this the Californian Mastitis Test (CMT; a crude test for cell counts in milk) should be used with caution in goats. Scientists in the USA recorded SSC from nearly 27,000 goats and found that SCC in goats (and cows) increased with stage of lactation, and parity. By the fifth parity counts for goats were in excess of 1,150,000 cells/ml, exceeding the legal limit of 1,000,000 cells/ml in the US, whereas maximum counts for cows averaged on 300,000 cells/ml (Paape et al., 2007).

Bacteriological culture to test for cause of mastitis

Bacteriological culture can be used to determine the true infection status of the udder. It can give an indication of which pathogens are present in the herd. This knowledge can be used to guide interventions (Koop et al., 2012).

Diagnosing mastitis in your does

Diagnosis is based on bacterial cultures of milk, and an SCC. However SCC should be interpreted carefully as non-infectious factors can influence the results (See above).

Mastitis develops when bacteria invades the udder. Regular inspection and keeping the teats clean is important in preventing mastitis.

Control and Prevention

Nannies affected by mastitis should be isolated, milked last and ultimately culled as this reduces exposure of other does, and increases selection pressure for genetic resistance. In herds where there is a high incidence of mastitis udders should be checked regularly and any lesions present should be treated immediately.

Prevention measures include:

- Improved sanitation – supply plenty of clean and dry bedding

- Hygienic milking practice

- Implementing a milking order, e.g., milk primiparous and / or healthy females first – this has been shown to work in France (Bergonier et al., 2003)

- Dry Period treatment

- Isolating cases

- Culling persistent infectors

Treating Mastitis

Treatment depends on the severity of the infection. Microorganisms associated with mastitis in dairy goats are commonly controlled with antibiotics, but it is known that continued use of these chemical agents promotes antibiotic resistance among bacterial populations (Gutiérrez-Chávez et al., 2016).

Mild cases may respond to a localised treatment using an intra-mammary preparation of antibiotic into the infected udder, after the teat has been striped out. More severe cases will undoubtedly require more aggressive treatment and you should consult your farm vet (Harwood, 2006).

In New Zealand, researchers looked at the benefits of using CMT as a screening test and concluded that its use resulted in a higher likelihood of finding a gland that would be infected than selecting a gland at random. They also tested treatment (those with a CMT score >1) vs no treatment (Those with a CMT score <1) and found that treatment increased bacteriological cure rate and reduced SCC at gland level compared with no treatment. However, at goat level, milk yield, SCC, and survival were not altered, resulting in no economic benefit of treatment (McDougall et al., 2010).

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

Preventing mastitis in your herd

Good milking hygiene will minimise the risk of infection and spread of disease:

- Keep the milking machine serviced

- Use meticulous milking hygiene

- Good husbandry and regular inspection of does udders is essential to avoid suffering so ensure you check udders before milking looking for signs of swelling

- If the goats teats are clean prior to milking avoid washing them, however if they are dirty wash and dry them before milking

- Ensure you pre- or post-dip (which ever works for you) all of the teats

- Treat cases promptly when recognised

- Separate infected and high SCC does into their own milking group and milk last

- Taking samples from all new cases of mastitis is good practice and can help to identify the pattern of infection in a herd and therefore can help in targeting the most effective control measures

- Isolate infected does to avoid spreading the disease throughout the herd

- Cull animals with chronic mastitis, or incurable cases as they will only act as a reservoir for infection

Provision of plenty of clean, dry bedding is required in order to minimise the risk of mastitis. Farmers should assess the cleanliness of their animals regularly and if they are dirty, find out why.

Keep the housing conditions as clean and dry as possible:

- Do not use wet bedding

- Re-bed as often as you can

- Make sure the housing is not overcrowded

- Respond to changes in weather by increasing bedding when very wet

- Avoid water troughs in the bedding area

- Assess the cleanliness of your does regularly

Controlling mastitis in your herd

Record Keeping – If mastitis is a problem on your farm you should create and maintain a mastitis monitoring system, and be recording the following details:

Find the cause of mastitis on your farm

- It is important to know what is causing mastitis in a herd, in order to try and prevent it. The best starting point is to carry out bacteriological examinations.

- Also monitor somatic cell count but remember to take into account the non-infectious factors that can increase SCC in goats (oestrus, parity, stage of lactation, stress)

- Decision-making about drying off and culling should be based on SCC recordings and bacteriological examinations

- Name/number of the doe

- Affected teat

- Dates, duration of infection

- Frequency and type of treatment

- Length of the statutory withdrawal period

- Outcome of the treatment (e.g. success/failure/lost quarter/cull/removal to suckling etc.)

American English

American English

Comments are closed.