Poultry Diseases

Gapes

Also known as: Syngamus trachea

Gapes is most likely to be seen in free-range systems because earthworms and other invertebrate hosts such as slugs and snails are an important source of infection. The life cycle of the nematode can be direct or indirect. Most often it is indirect and involves an accidental paratenic host most frequently the earthworm. Game and wild birds provide a reservoir for the parasite.

Gape worms are bright red, with the male measuring 2-6mm and the female 5 to 20mm. The male becomes firmly attached to the tracheal wall and is in almost permanent copulation with the females, forming an easily distinguishable Y-shape.

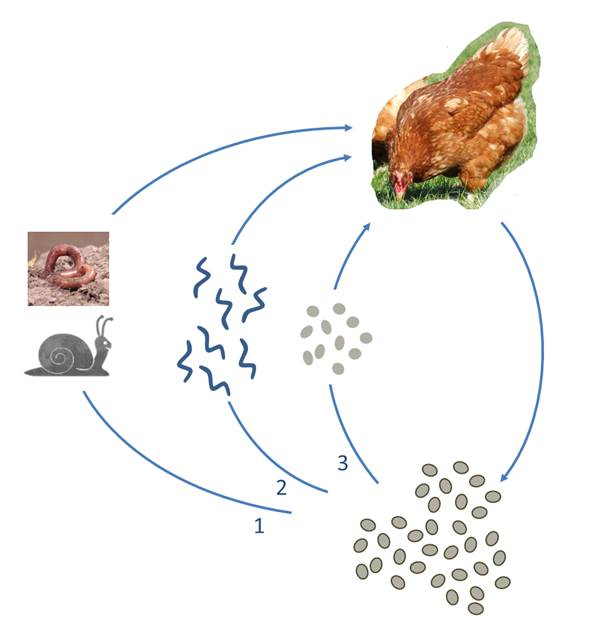

The life cycle of roundworm Syngamus trachea can follow one of 3 pathways, it can either be direct (routes 3 and 2), or indirect (route 1) via a transport or paratenic host such as earthworms, slugs, snails, beetles or flies.

The Life Cycle of Syngamus trachea

Eggs produced by the female worm are carried by mucus up the trachea where they are swallowed and eventually passed out of the bird in faeces. Under optimal temperature and humidity levels, the egg undergoes a third stage, moulting to produce an infective larva. Eggs containing larvae have been reported to survive on pasture and up to 9 months in soil (Taylor et al., 2007).

Eggs on pasture may infect birds in three different ways:

- The infective larvae may remain in the eggs and become ingested by birds in this form

- The larvae may hatch in the environment on about day 9, and be directly ingested by birds. In this form the larvae are easily killed by desiccation from sunlight, although they may survive for many weeks in shaded areas.

- The larvae may be ingested by a paratenic host, such as earthworms, slugs, snails, beetles or house flies. The larvae penetrate the intestinal walls of the invertebrate hosts and can remain there for years. Since an invertebrate host may accumulate many larvae, ingestion of a single intermediate host by a single bird can result in a severe infection.

After ingestion of the worm larva it migrates in the bird from the bowel to the lungs via the blood stream. Larvae undergo a fourth stage moult at about the third day after ingestion, and undergo a fifth larval stage in the bronchi of the lungs on the fifth day of infection. By the seventh day of infection the parasite is found in the trachea. They reach sexual maturity twelve days after this and eggs can be found in poultry faeces 18 to 20 days after infection.

Adult turkeys often act as carriers for the roundworm that causes Gapes, Syngamus trachea, shedding low levels of eggs, contaminating the pasture or ground for more susceptible birds. Image copyright of Animal Welfare Approved.

Gapeworm infection primarily affects young domestic chickens of less than 2 – 3 months old as this is when infected chicks usually develop and age-related resistance, but turkeys of all ages are susceptible, the adults often acting as symptomless carriers (Taylor et al., 2007). Disease is most often seen in breeding and rearing units with outdoor pens such as those used for breeding pheasants. Infection is highest in summer when earthworms and other invertebrate hosts are active (Taylor et al., 2007). Although gapeworms are only rarely found in mature layers, the parasites can survive in poultry birds as long as to 147 days in chickens (Wehr, 1939). They are more often found in adult turkeys.

Gape worms are not commonly seen in poultry reared on impervious floors. Only chicks up to 8 weeks of age are susceptible. Most commercial poultry units now involve rearing of chicks in systems where they are not in constant contact with their droppings and not ingesting earthworms which will reduce the incidence of gapes. The disease can be found in turkeys kept on dirt floors.

The related parasite Cyathostoma bronchialis causes a similar condition in geese.

Control and Prevention of Gapes

Young birds should not be reared with adults, especially turkeys, and to prevent infection becoming established poultry yards should be kept dry and free from wild birds (Taylor et al., 2007).

Researchers in the South West of the UK investigated the special distributions of S. trachea eggs in 10 pheasant release pens and reported that faecal contamination of feed is the primary method of parasite transmission, as a very high proportion of eggs were ‘clumped’ around feeding sites (Gethings et al., 2015). On farms with a high incidence of gapes, one method to reduce the risk of infection could be to frequently move of feeders, or the use of feeders that limit the amount of faecal–grain contamination (Gethings et al., 2015)

Preventing the birds ingesting infected paratenic host , especially the earthworm will minimise risk of infection. However, this may not be feasible or desirable in ranging systems. Poultry given access to newly ploughed fields may be at an additional risk as a consequence of a large earthworm population.

Where there is a risk, turkeys and pheasants should not be kept near chickens, as cross-infection may occur. Furthermore, chickens should not follow turkeys in a rotation.

See also general control and prevention section in helminthiasis of poultry.

Treating Gapes

Gapeworm eggs may be microscopically detected in faeces and the condition treated with in-feed preparations of the anthelmintics such as thiabendazole, mebendazole or flubendazole.

See also general treatment section in helminthiasis of poultry.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

- Chickens should not follow turkeys in a rotation

- Do not rear young birds with adults

- Minimise attractants and/or deter wild birds, to stop them mixing with poultry on the range

- Avoid keeping poultry where they have access to newly ploughed fields

- Turkeys and pheasants should not be kept near chickens

See also recommended good practice section in helminthiasis of poultry.

American English

American English

Comments are closed.