Sheep Diseases

Border Disease in Sheep

Also known as: Hairy-shaker Lambs

Border disease is a form of infectious abortion in sheep (Nettleton et al., 1998). On individual farms it can cause serious losses (Sharp and Rawson, 1986). The disease is characterised by poor scanning rates, barren ewes, abortion, stillbirths and the birth of small, weak lambs; a variable percentage of which show tremor, abnormal body conformation and hairy fleeces also known as “hairy-shaker” or “fuzzy” lambs (Jeffrey and Roeder, 1987). The cause of border disease is a virus related to bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) virus (Nettleton and Entrican, 1995) and swine fever (hog cholera) virus (Edwards et al., 1995), the three viruses being grouped in the genus Pestivirus. Border disease virus can also infect goats, pigs and cattle (O’Neill et al., 2004).

Control and Prevention

Treatment Options

What about welfare?

Good Practice

Transmission of Border Disease

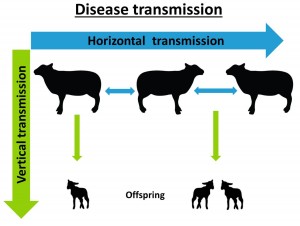

Vertically transmitted infection is when disease is transmitted from one generation to another and can be either in utero via the placenta, or lactogenically, via the mother’s milk. Horizontal transmission is disease transmission from one animal to another.

Border disease virus spreads naturally by horizontal and vertical transmission (see diagram). Infection of healthy non-pregnant sheep with the virus causes only a very mild disease, which often passes unnoticed by the shepherd. However, the disease is very serious in susceptible pregnant sheep because the virus can cross the placental barrier and infect the foetus. The ewe shows no disease, but the foetus, once infected may be aborted or stillborn.

The outcome of the foetal infection depends on the stage of foetal development at which infection occurs (Jeffrey and Roeder, 1987; Roeder et al., 1987):

(i) Foetal lambs infected after 85 days of gestation have an immune system capable of destroying the virus, so foetal death is rare and virtually all lambs are born normal, with detectable antibodies to the virus.

(ii) Foetal lambs infected in early gestation, before 85 days, will either abort or survive, but as infection is prior to the development of the foetal immune system, damage to the developing nervous system and skin may result in ‘hairy shaker’ lambs.

Any surviving lambs that have been infected earlier in gestation will be persistently infected with the virus (Nettleton et al., 1992). Some of these carriers mature normally and excrete the virus in all body fluids (e.g. saliva and urine) throughout their lives (Barlow et al., 1980). The persistent infection is due to the fact that the lamb is immunotolerant to the virus, meaning that it accepts it and never mounts an antibody response against it (Sandvik, 2014; Terpstra, 1981; Westbury et al., 1979; Woldehiwet and Nettleton, 1991).

Persistently infected lambs that reach maturity (Nettleton et al., 1992) often have a slow growth rate (Roeder et al., 1983; Sweasey et al., 1979) and reduced fertility. Females that conceive either abort or produce persistently infected lambs, sometimes over a number of years. Rams usually have soft testicles, but can transmit virus in their semen as well as other secretions (Gardiner and Barlow, 1981).

In some persistently infected lambs a subtle change occurs in the virus, and the immunotolerance it has established with the host’s immune system is upset. This usually occurs when the lambs are 2-6 months old and results in damage to the inner lining (mucosa) of the gut, causing unremitting diarrhoea and death (Monies et al., 2004; Nettleton and Willoughby, 2007).

Control and Prevention of Border Disease

Many livestock farmers, graze sheep and cattle together, which increases the risk of bovine viral diarrhoea infection in sheep (Sandvik, 2014) and border disease in cattle (Braun et al., 2005). Therefore, ewes in early pregnancy should not be mixed with cattle.

Sporadic outbreaks can be controlled by removing the entire lamb crop and the sheep suspected of introducing the infection (Barlow et al., 1980).

Treating Border Disease

There is no treatment for border disease. If a control programme requires slaughter of infected animals, this should be done humanely.

Border Disease and Welfare

While the initial maternal infection is usually subclinical or mild, the consequences for the foetus are serious. Surviving lambs from ewes infected during the first half of pregnancy may be born with a hairy birth coat and a tremble (hairy-shakers). The majority of these lambs die because they cannot keep up with their mothers, or cannot suck colostrum because of the trembling. Other lambs may appear quite normal but develop fatal diarrhoea or waste away within weeks or months of birth (Henderson, 1990). These clinical conditions, caused by border disease, are a real welfare problem, and farms should therefore be protected from the disease.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

If border disease is known to be present on the holding, sheep should be blood tested and those with a positive antigen titre for border disease removed from the flock. Otherwise:

- Maintain a closed flock

- If this is not possible, bought-in sheep should be kept separate and blood tested for the presence of the virus and quarantined for approximately 1 week until declared free from infection

- Untested bought-in ewes should come from border disease free flocks, be tupped separately and be kept apart from the main flock until lambing time. Contact with surrounding flocks should be avoided through good fencing

- In the case of an outbreak of border disease, remove the entire lamb crop and the sheep suspected of introducing the disease. If the source is unknown, the entire flock should be blood tested after an outbreak to identify reactors, and these should be removed

- Every effort should be made to eradicate the disease from a flock in which the disease is endemic. The entire flock should be blood tested to identify persistently infected animals, and these should be removed

American English

American English

Comments are closed.