Sheep Diseases

Sheep Scab

Also known as: Mange – Psoroptic, Scab

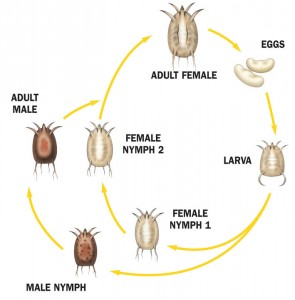

In ideal conditions, the life cycle of the sheep scab mite Psoroptes ovis from egg to adult takes 14 days. Mites can live off host and remain infective in brambles, on fences and scratching posts and in wool tags for up to 18 days. This is important when considering treatment options, as if treated sheep need to be turned back out on to pasture that has been grazed by infected sheep in the past 3 weeks, they must be treated with a persistent drug.

Sheep scab is a caused by a parasitic mite called Psoroptes ovis, which is a skin surface feeder. Infections are a major welfare concern as they can be debilitating with high morbidity, and fatalities can occur through loss of condition, malnutrition, secondary infections and hypothermia (Bates, 2007). Sheep scab is a time-consuming and expensive condition to treat, which can be avoided through vigilant flock biosecurity.

Sheep scab is often referred to as a winter disease as most cases occur from autumn through to spring, although a number of cases do occur in the summer months.

The mite is specific to sheep in the UK, but is a major problem in cattle in mainland Europe. The mite is just visible to the naked eye; its entire development takes place on the skin surface, although it can remain viable off host for 16-18 days. The female only requires fertilising once before she lays 2-3 eggs per day, which hatch after 1-2 days, and she lives for about 40 days.

After hatching, the parasite passes through the larval stages, the nymph stages, then on to adulthood. During the nymph stages the mite does not feed, which is an important factor to consider when using injectable endectocides to treat scab. The male usually attaches itself to the pubescent female, but copulation does not take place until the female has moulted to the adult stage. The life cycle is completed in 14 to 17 days (Lewis, 1997).

Transmission of Sheep Scab

Sheep scab can be contracted via contact with live mites in tags of wool, or scabs attached to fences, barbed wire, brambles, and bushes etc., but the usual mode of transmission is sheep-to-sheep contact, especially in livestock markets and trailers. Shearing equipment and clothing can also spread scab (Bates, 2007).

Clinical Signs of Sheep Scab

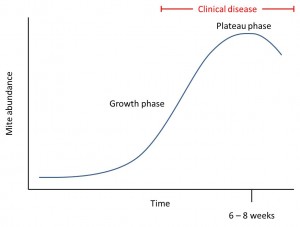

In the early stages of infection when mite numbers are low, the problem will not be obvious. However within 6-8 weeks, mite abundance will have multiplied massively, the lesion will have spread, sheep will rapidly lose condition and clinical disease will be apparent. Sheep scab mites cannot feed on hardened scab so they will be located around the periphery of the lesion.

In the early stages of infection, when the mite numbers are low, there might not be any obvious clinical signs. Sheep with sub-clinical scab can look perfectly normal and can unknowingly be introduced to the flock (Bates, 1997). Psoroptes ovis mites pierce the epidermis of the skin to feed mainly on lymph. Yellowish pustules develop that rupture, the exudation forms typical yellowish crusts and the fleece becomes moist and matted. Earlier crusts will darken and come away from the skin with the remaining wool.

The intense irritation results in the sheep becoming hypersensitive, ‘nibbling’ characteristically when touched, or even rolling on the ground in an involuntary paroxysm. The interaction of bacteria and digestive enzymes on the skin surface of the sheep may be responsible for the excessive inflammatory reactions evident in clinical sheep scab (Hamilton et al., 2003).

Sheep with scab show increased incidences of scratching with the hind leg, rubbing or itching their sides and tail on inanimate objects like a fence or wall, mouthing movements, head turning and pulling on their wool, stretching backwards and tossing their heads, trying to use ears or horns as an itching tool and chewing affected limbs. The time spent in these activities eventually interrupts their normal lying and eating behaviour pattern.

The movement of mites is strongly directed towards areas of high temperature but away from higher light intensity. This behaviour probably helps the mites maintain their position on a host animal, and helps them locate the skin surface of a new host when they are displaced into the environment (Pegler and Wall, 2004). The mites can survive off host for 16-18 days, and they are found on areas where infected sheep like to rub against, or in wool casts.

It has been suggested that P. ovis elicits an early innate cutaneous response in sheep that is then augmented by the development of an adaptive immune response. The intensity of the response is dependent on the population density of mites (van den Broek et al., 2004).

Control and Prevention of Sheep Scab

Shearing can stop the progress of sheep scab (either temporarily or permanently), by removing the microclimate, leaving the mites exposed to dehydration (Bates 2007). However, the mites can be spread from animal to animal on shearing equipment and clothing.

Keeping closed flocks will prevent the disease from entering the flock (Evans, 1992), as the greatest risk of disease is through imported stock. If a closed flock is not possible, shared tups and all new or returning stock should be isolated for 3 weeks, treated according to SCOPS principles and observed for signs of scab. It is however worth remembering that the very early stages of sheep scab are not always obvious initially.

Areas of common grazing, where sheep can freely roam from one area to another, can lead to rapid disease spread and considerable problems in tracing flock origins and ensuring satisfactory treatment. A collaborative approach to controlling sheep scab, particularly in areas with dense sheep populations, is likely to be more successful than the frequently unsuccessful efforts of individual farms (Sargison et al., 2006).

Diagnosing Sheep Scab

If sheep scab is suspected, a definitive diagnosis to confirm it is scab (caused by a mite) and not sheep lice, could save considerable time and money, as injectable drugs used to treat sheep scab do not kill lice. Lice cause similar conditions to scab, however they predominantly affect sheep in poor condition, whereas scab mites do not target any sheep in particular.

Most vets and animal health labs will take a skin scraping and look at the sample under the microscope to differentiate between a lice and mite infestation. Not only are thousands of pounds wasted by farmers every year treating the wrong parasite, but incorrect treatments also lead to resistance to products.

Treating Sheep Scab

The two treatment options for sheep scab are injectable macrocyclic lactone or plunge dipping. Sheep dips contain organophosphates which are highly toxic to all aquatic life and are extremely bad for the environment. Dip residues are regularly detected in watercourses.

Injectable Macrocyclic Lactones (ML) for Treating Sheep Scab

The dose of ML needed depends on the weight of the animal, so careful calibration and measuring is required to ensure that the product is fully effective. There are 3 different MLs that can be used to treat sheep scab and each has their advantages and disadvantages, which are outlined in the table below.

Active chemical |

Administration |

Dose |

Persistent protection |

Notes |

| Ivermectin | Subcutaneous injection | Two injections 7 days apart | No persistent protection | Animals must be moved to new pasture as this drug offers no persistent protection |

| Moxidectin 1% | Subcutaneous injection | Two injections 10 days apart | 28 days persistent protection | Moxidectin 1% should never be given to sheep that has had Footvax

Moxidectin cannot be given to sheep under 15kg |

| Moxidectin 2% | Subcutaneous injection at the base of the ear | One injection | 60 days persistent protection | Moxidectin cannot be given to sheep under 15kg |

| Doramectin | Intra-muscular injection | One injection | No persistent protection | Kills mites from all life stages (hence one injection). Animals must be moved to new pasture as this drug offers no persistent protection

Can only be used in sheep heavier than 16kg |

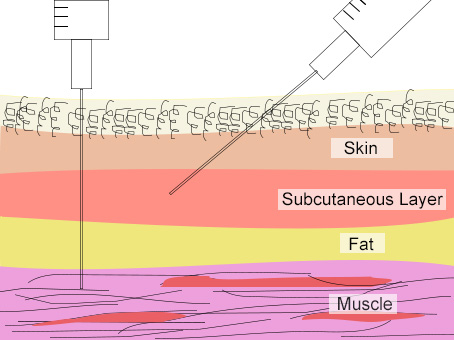

Care must be taken when injecting animals that the treatment is deposited where it is intended to be. Animals should be restrained before they are injected. Injectable MLs are either administered as a subcutaneous injection usually 10-15cm (4-6 inches) below the ear, a subcutaneous injection in the ear (Moxidectin 2%) or via intra-muscular injection (Doramectin) usually in the mid neck, 10-15cm (4-6 inches) in front of the shoulder, above the large jugular vein, avoiding spoiling the meat.

Farmers should be aware that there is evidence to suggest that residues of MLs are excreted in dung at levels which are toxic to insects, such as the dung beetle (Wall and Beynon, 2012).

As ML products are also very effective against internal parasites, it is essential that both internal and external parasite controls are considered together. The current incidence of ML resistance by gastro-intestinal parasites is increasing worldwide, and ML products offer an alternative treatment where white and yellow drench resistance is suspected. However, restrictions on dipping chemicals have resulted in the greater use of ML products for scab control.

Sheep Dipping

An alternative to ML injectable drugs is plunge dipping sheep. The main ingredient of dipping formula is organophosphates (OP), which are toxic to humans and hazardous to the environment. In the UK farmers need a certificate of competence to be able to dip sheep. The dipping process is labour-intensive, and stressful to the sheep. They must be immersed in the dip for one minute, and the head must go under twice in that time. Dipped sheep must be allowed to drain, and must not be returned to the pasture until excess dip has drained out of their fleece.

Plunge dipping, if done correctly, can be exceptionally effective in controlling sheep scab and many other ectoparasites, including blowfly, ticks and lice. It kills all life stages of the mites quickly, and protects against re-infection, however due to its toxicity, it should only be used as a last resort for controlling ectoparasites.

Sheep Scab and Welfare

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

- Maintain a closed flock

- Talk to the farm vet or animal health adviser immediately as differentiation between mite and lice infection is important in determining treatment

- Decide on a suitable product to treat with, and ensure you treat all in-contact sheep to prevent recurrence

- Keep treated stock out of recently grazed pastures for at least 3 weeks.

- Treat sheep with scab lesions with topical and/or injectable antibiotics

- Talk to your neighbours

- Try to find the source of infection

- Isolate bought-in sheep and those returning from livestock markets, treat them according to SCOPS principles isolation policy

American English

American English

Comments are closed.