Sheep Diseases

Coenurosis

Also known as: Gid, Staggers, Sturdy, Taenia multiceps

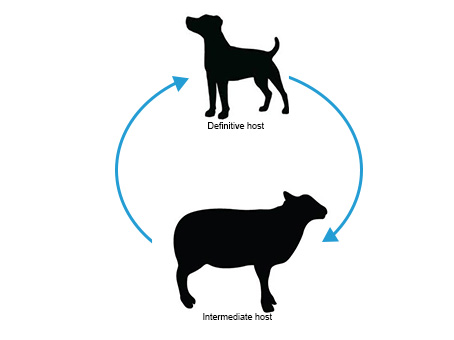

Coenurosis is a parasitic disease of the central nervous system. It is fairly uncommon, but seen in certain geographical areas. It is caused by a tapeworm (cestode) called Taenia multiceps (T. multiceps), which lives relatively benignly in the definitive canine host (including dogs, foxes, jackals and coyote) but causes significant disease in the intermediate host, where the larval stage of the tapeworm migrates to the brain and spinal cord and matures into a fluid –filled cyst. Sheep are the main intermediate host but there have been rare cases reported in cattle, pigs, deer, horses and humans.

The real prevalence of coenurosis is difficult to assess, because farmers and vets often diagnose the disease and send the animal for slaughter without confirmation or report. A large proportion of infected lambs may also be sold fat before clinical signs have developed (Herbert et al., 1984).

Dogs and other canines such as foxes, coyotes and jackals are the definitive hosts of the tapeworm Taenia multiceps. Canine hosts shed tapeworm eggs in their feces which contaminates the pasture for the intermediate host to ingest. T. multiceps infection on a farm is significant as it confirms an unbroken sheep and dog life cycle, which in turn implies the existence of more important tapeworms such as Echinococcus granulosus. This dog / sheep tapeworm usually infects sheep and forms cysts in the lungs and liver, which if consumed by humans will cause a very serious disease that is very difficult to treat. Surgery is the only option.

The life cycle of Taenia multiceps

- The intermediate host is infected through ingestion of T. multiceps eggs

- Each egg contains an onchosphere which hatches and is activated in the small intestine

- The onchosphere penetrates the mucosa and is carried via the blood stream to the brain or spinal cord. In goats the cysts can form in subcutaneous and muscular sites as well as the brain and spinal cord

- The onchosphere develops into a metacestode larval stage called Coenurosis cerebralis

- The Coenurosis cerebralis matures into a thin-walled fluid-filled cyst about 5cm in diameter

- The life cycle is complete when the canine eats the raw infected brain, spinal cord or offal contaminated by the fluid from the ruptured cyst. The scolex (head of the tapeworm) embeds itself into the wall of the small intestine where it begins to grow, and shed new eggs.

(Adapted from (Taylor et al., 2007))

Usually the Coenurosis cerebralis cyst persists for the life of the intermediate host.

Clinical Signs of Coenurosis

The clinical signs of the coenurosis develop when the central nervous system (CNS) of the sheep is invaded by the cystic larval stage, or metacestode of the tapeworm.

Coenurosis can occur in both an acute and a chronic disease form. Acute coenurosis occurs during the migratory phase of the disease, usually about 10 days after the ingestion of large numbers of tapeworm eggs. Young lambs aged 6-8 weeks are most likely to show signs of acute disease. The signs are associated with an inflammatory and allergic reaction. There is transient pyrexia, and relatively mild neurological signs such as listlessness and a slight head aversion. Occasionally the signs are more severe and the animal may develop encephalitis, convulse and die within 4 – 5 days (Scott, 2007). Acute disease is an important differential diagnosis for Cerebrocortical necrosis (CCN).

Chronic coenurosis typically occurs in sheep of 16-18 months of age. The time taken for the larvae to hatch, migrate and grow large enough to present nervous dysfunction varies from 2 to 6 months. The earliest signs are often behavioral, with the affected animal tending to stand apart from the flock and react slowly to external stimuli. As the cyst grows, the clinical signs progress to depression, unilateral blindness, circling, altered head position, in-coordination, paralysis (Bussell et al., 1997) and recumbency. Unless treated surgically, the animal will die (Scott, 2007).

The larval stages of tapeworm development, differ in form and occur in different hosts, which led early investigators to believe that they were in fact different species, hence the larval stages were given their own names. In the case of T. multiceps, the larval stage within the intermediate hosts is called Coenurus cerebralis.

Control and Prevention of Coenurosis

The best control and prevention of coenurosis is to prevent dogs from having access to sheep and cattle carcasses and not to feed them uncooked meat (Edwards et al., 1979). If this is not possible, the control and prevention of coenurosis should be based on routine anthelmintic dosing of dogs, preferably every three months.

Public footpaths running through the sheep fields used by people walking their dogs can be a particular problem (Bussell et al., 1997). Farmers could display a sign explaining the disease risks and encouraging local people walking their dogs on these fields to have their dogs wormed.

Treating Coenurosis

Currently the only treatment that can be recommended is the surgical removal of the coenurus cyst from the brain of the affected animal (Daly, 1985; Skerritt and Stallbaumer, 1984). This treatment can be very successful, and most cases will show a dramatic recovery, with return to full neurological function (Kelly and Payne-Johnson, 1993), however not all affected animals can undergo surgery as it largely depends on the location of the cyst (Doherty et al., 1996). The vet will have to decide whether there is a chance the animal will recover or whether it is better to destroy the affected animal humanely to prevent further suffering.

Coenurosis and Welfare

Coenurosis affects the central nervous system and causes paralysis and malcoordination (Bussell et al., 1997; Scott, 2007), with obvious welfare implications. It is therefore important to prevent sheep becoming infected in the first place.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

If cases of coenurosis are a regular occurrence on the farm, eliminating the disease from the farm should be part of the overall health plan. Efforts should be geared towards preventing dogs and other canines contaminating the pasture with tapeworm eggs, by stopping them eating sheep carcasses:

- Dispose of sheep carcasses quickly and correctly

- Worm residential dogs regularly (every 3 months)

- If possible local people walking dogs on the land should be encouraged to have their dogs wormed

British English

British English

Comments are closed.