Cattle Diseases

Bloat in Cattle

Also known as: Ruminal Tympany

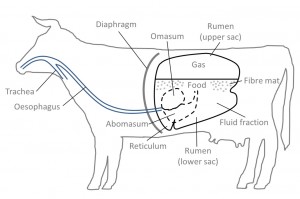

(Image adapted from Blowey, 2006)

Bloat is over-distension of the rumen caused by the accumulation of fermentation gases in the rumen. Primary bloat or frothy bloat is the more common form of the condition, and usually occurs as an outbreak in several animals on pasture that contains high levels of leguminous plants, clover in particular. Primary bloat can also occur in feedlot cattle. Secondary bloat or gaseous bloat is rare and occurs sporadically in an individual animal as a secondary manifestation of another pathological condition (e.g. physical obstruction of oesophagus, injury, tetanus, rumen impaction with cereal etc.). This page is devoted to primary pasture bloat.

Once the froth has formed in the rumen and the natural eructation is prevented, the rumen motility is initially increased, causing further frothing. Finally there is a loss of muscle tone and rumen motility. Death is a result of several factors, including the depressive effect of rumen distension on the heart and lungs and absorption of toxins from the rumen.

As there are individual differences in the ability of cattle to tolerate rumen distension and in the presence of contributory factors in any given situation, some animals only suffer sub-clinical or mild bloating on clover-rich pastures. While the toleration of mild bloat allows adaptation to new pastures, sub-clinical and mild bloat have been recognized as causing major losses on clover dominant pastures in the form of reduced feed intake and subsequent lower weight gains (Latimori et al., 1992; Rossi et al., 1997)

Bloat has long been recognized as a major problem in countries like New Zealand, where clover forms an important part of the pastures (Carruthers et al., 1987).

While certain legumes are a risk factor for bloat (red and white clover, lucerne), other legumes which contain a high content of condensed tannins are not. These include sainfoin and birdsfoot trefoil. The condensed tannins precipitate the protein and prevent the build up of froth. They also have been shown to have anthelmintic properties in sheep.

Bloat is commonly associated with pastures with high levels of certain leguminous plants, clover in particular.

Due to its association with clover, bloat has been considered a risk factor on organic farms, where clover can constitute more than 50% of the sward content. However, research in the UK on farms during the organic conversion period few cases were reported with less than 50% of farms reporting no cases of bloat during a 2 year period despite swards with high white clover content (Weller and Cooper, 1996). A similar study on conventional farms in Sweden reported zero cases of bloat despite all animals grazing high clover content (Frankow-Linberg and Danielson, 1997).

Bloat risk factors can be classified as either pasture or animal factors.

Pasture factors – Certain legumes (red and white clover, lucerne), frost, nitrogen fertilizers and wetness of pasture

The main risk factor in pasture bloat is the rapid ingestion of immature/fast-growing legumes in pre-flowering stages (Thompson et al., 2000). Alfalfa and tall white clover (ladino) are the most “dangerous” legumes, while red and white clover are only moderately so. An increase in bloat risk has been seen in experimental organic dairy pasture when the clover (Trifolium resupinatum and Trifolium repens) content increased at the end of the grazing season (Kuusela et al., 2004). Sporadic bloat outbreaks have also been reported on grazed cereal crops, rape, cabbages, peas and beans (Radostits et al., 2006).

Ingestion of only the most succulent parts of the plant in set grazing systems is an important risk factor, in addition to the sward type. Frost and growth of alfalfa at low temperatures have been shown to increase bloat risk by increasing the leaf cell constituents related to pasture bloat (MacAdam and Whitesides, 1996). High levels of nitrogen fertilization have been associated with both high and low incidence of bloat (Ledgard et al., 1990; Reason et al., 1989).

Wetness of the pasture has also been suspected to be a risk factor for bloat. However, it is more likely that the real risk factor is the fast growth brought on by wet and favorable weather. No increased risk of bloat was reported in a trial of feeding clover silages (red and white clover) to dairy cows (Bertilsson and Murphy, 2003).

In New Zealand emphasis is put on the sodium potassium ratio, otherwise referred to as the bloat index (Majak and Hall, 1990). Anecdotal evidence from the UK found reduced incidence when pastures were treated with sodium.

Animal factors – Age, inherited characteristics, and fasting

It is fairly well established that young animals are more susceptible to acute and severe bloat than older animals, and it is suspected that animals get used to eating bloating pastures and are less susceptible after exposure.

It has also been established that some cows can be classified according to their susceptibility to pasture bloat and that a number of inherited characteristics are related to bloat. These characteristics include the composition of salivary proteins and salivation rate and rumen capacity/girth measurement and motility (McIntosh et al., 1988).

Fasting has also been shown to predispose animals to pasture bloat, but the mechanism is not established. Dairy heifers have been demonstrated to selectively graze pastures with a 75% clover content such that they choose a 76% clover grazing preference and not suffer from bloat (Rutter et al., 2004).

Control and Prevention of Bloat

Several approaches to the control and prevention of pasture bloat have been experimented with in various parts of the world. These include:

- The manipulation of the composition of pasture (Barry and McNabb, 1999; Waghorn and Jones, 1989; Waghorn, 1990; Carruthers and Henderson, 1994; Majak et al., 1995, Rhodes and Webb, 1993)

- Grazing and feeding management during risk periods (Fay et al., 1986; Hall et al., 1984; MacAdam and Whitesides, 1996; Hall and Majak, 1991; Phillips et al., 1996)

- The use of anti-bloat agents during risk periods (Hall et al., 1994; Moate et al., 1999; Dougherty et al., 1992; Latimori et al., 1992; Rossi et al., 1997)

- The manipulation of herd susceptibility to bloat (McIntosh et al., 1988; Wheeler et al., 1998)

- Assessing and adapting the sodium potassium ratio

In New Zealand, a lot of emphasis has been placed on the genetic susceptibility of cattle and on intensive use of anti-bloat agents, while feeding and grazing management has been more common in the UK, in the absence of established breeding parameters for bloat resistance.

The risk of acute, fatal bloat or of sub-acute bloat that might affect feed intake in systems that have levels of clover in the sward above 50% has probably affected farmers’ willingness to create grazing systems with high levels of clover. In the organic grazing systems clover is a vital part of the sward, and the control and prevention of bloat has to incorporate this requirement. It is not acceptable to use anti-bloat agents intensively over long periods of time, due to the long withdrawal requirement for milk. Consequently, bloat control on an organic farm should concentrate on grazing and feeding management and, potentially, on the manipulation of pasture composition.

Bloat and Grazing Management

Grazing management should concentrate on pastures and animals most at risk: flush, pre-flowering, clover-rich pastures in the spring and autumn and young animals (young stock and first calvers) and animals that are kept in for the night and allowed access to risk-pasture after morning milking. Silage and hay aftermaths pose a high risk of bloat if there is a high clover content, therefore cattle should be turned out onto pasture as soon as possible after lifting the crop, when there is less clover present, as this allows the clover to grow up while being grazed (Younie, 2001).

Grazing management should concentrate on pastures and animals most at risk: flush, pre-flowering, clover-rich pastures in the spring and autumn and young animals (young stock and first calvers) and animals that are kept in for the night and allowed access to risk-pasture after morning milking. Silage and hay aftermaths pose a high risk of bloat if there is a high clover content, therefore cattle should be turned out onto pasture as soon as possible after lifting the crop, when there is less clover present, as this allows the clover to grow up while being grazed (Younie, 2001).

When the risk is considered to be great, strip grazing should be considered. An additional precaution could be taken by drenching animals daily with anti-bloat agents. However, it should be noted that the Bloat Guard Drench by Agrimin has a statutory milk withdrawal of one day, which is longer under different organic certification schemes. Similarly, the use of Birp (Arnolds) and Bloat Guard Premix (Agrimin), which do not have statutory withdrawal periods, would require at least 48-hour milk withdrawal under organic schemes. Organic farmers must check this with their own organic certifiers.

Animals that are kept housed for the night should be given hay or silage before turn out to ensure good fiber intake before grazing on at-risk pastures (Younie, 2001). Supplementation with corn silage at 0.5% and 1% of body weight before grazing lucerne has been reported to reduce bloat occurrence and severity (Bretschneider et al., 2001). One study found that cattle have a strong diurnal preference for clover grazing, with increased intake in the morning (Rutter et al., 2004). In this case, it may be useful to be especially careful to supplement dairy cows at and after morning milking so they are less likely to gorge on clover.

Close observation of animals during at-risk periods should be maintained, and at first sign of bloating the above-mentioned precautions should be taken. If clinical bloat does occur, the affected animals should be treated and the others should be removed immediately from the pasture and provided with hay or straw. The risk pasture should not be grazed for at least 10 days. All animals with signs of sub-clinical, mild bloating should be drenched with anti-bloat agent.

Bloat and Pasture Composition

It has been suggested that the presence of dock leaves in the diet can reduce the occurence of bloat.

While there were earlier efforts to develop bloat-safe cultivars of clover (Rumbaugh, 1985; Rhodes and Webb, 1993), these have been more or less abandoned. Tannin-containing forage crops, including use of alternative forages, such as chicory, have been shown to reduce the risk for bloat (Waghorn, 1990; Barry and McNabb, 1999; Ramirez-Restrepo and Barry, 2005), but more research is needed to define necessary levels of intake of tannin-containing crops and their inclusion in pastures in a practical manner. A team of researchers in New Zealand have found bloat did not occur when docks (Rumex obtusifolius) were included in the cows diet, this is due to the presence of condensed tannins which aid ruminal digestion (Waghorn and Jones, 1989).

Use of sodium as a fertilizer may help reduce bloat risk from clover pastures (Phillips et al., 2001).

Treating Bloat

Treatment of acute bloat usually requires the passing of a stomach tube and administration of vegetable oil or anti-bloat agents. If the animal is distressed, drenching without a stomach tube should not be attempted as this easily leads to aspiration pneumonia.

Under organic conditions, proprietary anti-bloat agents require a milk withdrawal period twice as long as the label withdrawal period. The ones that do not indicate a statutory milk withdrawal require a minimum milk withdrawal of 48 hours. The prolonged withdrawal periods should be taken into consideration for meat withdrawal as well. Some certification bodies may operate a stricter withdrawal policy, and this should be checked before the inclusion of milk from the treated animals into the bulk tank.

In severe cases, where death is imminent and the animal is lying down, emergency surgery (rumenotomy) by a veterinarian is necessary.

Homeopathy has been recommended as a support treatment alongside stomach tubing and drenching with oil or anti-bloat agents (Macleod, 1981; Hansford, 1992).

Bloat and Welfare

As acute bloat is often fatal, every precaution should be taken to prevent occurrence under at-risk conditions (autumn/spring, lush, wet pasture, fasted animals, young animals etc.).

If an outbreak occurs, unaffected animals should be removed from at-risk pasture and mildly affected animals should be treated with oil or anti-bloat agents to prevent further suffering.

Severely affected animals should be treated as emergency cases and seen by a veterinarian immediately.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

- Always introduce cows slowly to new pasture

- Ensure access to long fiber during the whole grazing season at pasture or prior to going to pasture

- Check cow regularly when grazing

- Be aware of and identify risk periods; train all personnel dealing with cattle to be aware of risk conditions for bloat

- Establish a routine procedure for risk situations (e.g. keep animals housed; strip graze; feed hay, straw or silage before turn out after milking or in the morning; drench with oil or anti-bloat agents; observe cattle more often during risk periods etc.)

- Treat clinical cases immediately by stomach tubing and administration of oil or anti-bloat agents, observe withdrawal periods (see Treating Bloat), remove other animals from risk pasture, treat milk cases with oil or anti-bloat agents

- Do not graze risk pasture again for 10 days

British English

British English

Comments are closed.