Cattle Diseases

Sheep Diseases

Nematodirus battus

Nematodirus is a thread-necked roundworm that causes disease in the small intestine of sheep, goats and occasionally cattle. Nematodirus infection is primarily a disease of abundance affecting lambs at spring time due to its unique development requirement which results in the ‘Spring Flush’.

Nematodirus is a thread-necked roundworm that causes disease in the small intestine of sheep, goats and occasionally cattle. Nematodirus infection is primarily a disease of abundance affecting lambs at spring time due to its unique development requirement which results in the ‘Spring Flush’.

Ingested third stage larvae (L3) disrupt the mucosa in the small intestine affecting absorption, and causing protein loss, profuse watery diarrhea, dehydration and weight loss. The fleece is often dull and rough and the lambs may show the typical ‘tucked-up belly’ appearance. Weight loss can be rapid, with severe dehydration, and if the infection is untreated mortality can be high. It is a disease of abundance as infection in low numbers of this roundworm rarely causes clinical disease.

Coccidiosis causes disease in lambs of around the same age, so careful differentiation and diagnosis is recommended. Both infections can occur together, and with severe consequences.

Nematodiriasis in calves

Nematodirus battus, mainly a parasite of sheep, has been found to be transmittable by cattle, both on farms where annual alternation of sheep and cattle has taken place, and even where cattle only are kept. It has caused severe outbreaks of diarrhea in calves (Armour et al., 1988; McCoy et al., 2004). Nematodirus larvae have been seen to emerge later on pasture than other roundworms (Eysker et al., 2005) and therefore the epidemiology of this condition may not be so easy to predict, although it should be considered when cattle and sheep share the same grazing.

The Spring Flush

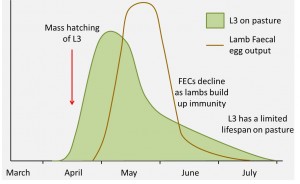

The spring flush: Around spring time, the majority of the Nematodirus eggs on the pasture, that have overwintered as they were deposited the previous season hatch and become infective around the same time. The pasture transforms from reasonably ‘safe’ to high risk due to the shear abundance of infective L3 simultaneously hatching. The abundance of L3 decline as the are ingested by ewes and other lambs. However lambs will gradually build up a strong immunity as a result of exposure.

Unlike most other gut ruminant roundworms the L3 develop fully inside the egg, as opposed to hatch as L1 or L2 and develop to L3 on pasture. The egg protects them in harsher climates and can overwinter. Hatching is triggered when, after a cold spell (winter), temperatures reach 50-59°F. The outcome of this is a huge flush of infective L3 hatch onto the pasture in early spring, hence the name spring flush.

These L3 infect new lambs before weaning damaging the small intestine, causing inflammation, and severe protein and water loss resulting in diarrhea and dehydration. It often happens suddenly and mortality can be high. As the clinical symptoms are caused by the worm larvae, FECs are not always useful to diagnose Nematodirus infection in young lambs at the early stage of the disease, as by the time eggs are detected in the feces, infection has already occurred and it is often too late. However, FECs can be used to confirm an outbreak. Lambs that do survive and recover often acquire a strong immunity to re-infection.

The spring flush does not always cause disease for if it happens very close to lambing the lambs will probably not ingest enough L3 to cause disease. Most problems are seen if the spring flush occurs while lambs of 6-12 weeks of age are grazing the pasture.

Ewes are thought to play a minor role in Nematodirus, unlike the other roundworms causing parasitic gastroenteritis.

In recent years more and more cases of autumn disease are being reported. Eggs deposited in spring are becoming capable of hatching the following autumn of the same year possibly as a result of evolution as they do not seem to require the cold spell followed by a mean temperature of 50 – 59°F to trigger hatching (Taylor et al., 2007).

In the UK, Norway, Sweden, The Netherlands and some parts of Canada, the main species present is Nematodirus battus (Taylor et al., 2007). Other species such as Nematodirus filicollis and Nematodirus spathiger are less pathogenic and infective L3 hatch over an extended period (Jackson and Coop, 2007). Nematodirus spp eggs present in feces are relatively large and easily distinguishable.

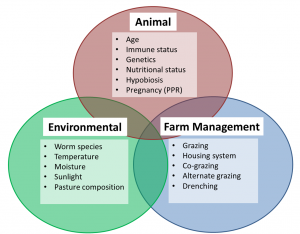

Factors that affect parasitic gastroenteritis can be divided into:

- Animal factors – including age and genetics.

- Environmental factors – including climate factors such as temperature, humidity and sunlight

- Farm management factors which are grazing system and pasture management. Pastures grazed by lambs in subsequent years are of particular risk.

Full detail of these factors can be found on the main PGE in ruminants page, however age-related immunity is particularly relevant to Nematodirus as young lambs are susceptible to disease and older stock will develop strong immunity.

Click here to read about the factors affecting epidemiology in more detail.

Control and Prevention of Nematodirus

Where Nematodirus is a problem, control mainly relies on avoiding putting susceptible lambs on high risk pasture, which is essentially ground grazed by similar aged susceptible lambs the previous year.

Awareness of the spring flush accompanied by regular FECs (although eggs are not always seen in early infections) will help recognise infection as mass-hatching is temperature-dependent and relatively predictable using March soil temperatures. NADIS do a ‘Nematodirus forecast’ based on predictions using this. It can be found here: www.nadis.org.uk/parasite-forecast.aspx

Ideally, lambs should not be grazed on land grazed by similar aged lambs or calves during the previous year. Calves, aged six months, grazing on pasture on which lambs infected with N. battus had grazed the previous season, became infected and passed eggs of N. battus. Transfer of these calves onto ‘clean’ pasture showed that their fecal contamination was sufficient to cause moderate infections of N. battus in lambs grazing this area the following season (Coop et al., 1991). Alternating lambs and cattle can work as a strategy to reduce worm burden with some species of GI nematode, but it should be avoided where possible on farms where Nematodirus is a problem.

On the main PGE in Ruminants page, control and prevention is divided into the various grazing and management strategies which can be combined to form an integrated control plan. The sections covered are:

- Fecal Egg Counting

- Mixed Grazing

- Alternating Stock

- Rotational and Evasive Grazing

- Extensive Grazing and Stocking Density

- Cutting and Reseeding Pasture

- Pasture Composition

Treating Nematodirus

Unlike other strongyles causing parasitic gastroenteritis, FEC are of little value in early diagnosis, which is best determined on clinical signs, grazing history and if possible post-mortem. Nematodirus spp are still largely susceptible to group 1 anthelmintics, the benzimadazoles. This is worth bearing in mind, particularly on farms who have known BZ-resistance, as the resistance is likely to be in the other species of roundworm e.g., Teladorsagia circumcincta, Trichostrongylus spp and Haemonchus contortus. However reports of resistance are beginning to emerge (Mitchell et al., 2011) so it is wise to do a ‘drench check’ 10-14 days later to ensure the anthelmintic has been effective. Click here to find out more about testing for resistance and drench checks.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

- Be mindful of the ‘spring flush’

- Check for Nematodirus forecasts on the NADIS website

- Where Nematodirus is a known problem, prevent the lambs from grazing fields grazed by lambs or calves in the previous year

- Base diagnosis on clinical sings and grazing management

- Undertake a drench check to ensure any treatments have been effective

British English

British English

Comments are closed.