Cattle Diseases

Sheep Diseases

Goat Diseases

The main parasitic gastroenteritis in ruminants page can be found here.

Haemonchus contortus

Haemonchus contortus infects sheep, goats, deer, and cattle especially in warmer parts of the world. It is often referred to as the barbers pole worm due to its resemblance to the red and white barbers pole when the intestine is full following blood meal. It resides in the abomasum of its ruminant host and is considered as a roundworm that makes up the parasitic gastroenteritis complex, however it does not conform to the typical pattern and can cause a breakdown in control so should be considered separately.

Haemonchus contortus infects sheep, goats, deer, and cattle especially in warmer parts of the world. It is often referred to as the barbers pole worm due to its resemblance to the red and white barbers pole when the intestine is full following blood meal. It resides in the abomasum of its ruminant host and is considered as a roundworm that makes up the parasitic gastroenteritis complex, however it does not conform to the typical pattern and can cause a breakdown in control so should be considered separately.

The main characteristics of this roundworm that need to be considered are:

- It is a blood feeder making it highly pathogenic

- Very fecund female worms

- Adult animals build up little immunity

- Uses hypobiosis in order to persist through winter

- Also causes disease in Cattle

Haemonchus is a blood feeder

Unlike the other gut roundworms often found in ruminants, H. contortus is a blood feeder. It is the adult worms that cause harm as they have a piercing lancet at their head end which is used to cut to the mucosal lining in the abomasum, enabling them to suck blood. When the worms move on to feed at new sites the damaged mucosa continues to bleed. Each worm can remove about 0.05ml of blood per day so small ruminants with 5000 H. contortus may lose about 250ml daily (Taylor et al., 2007).

Diarrhoea is not a characteristic symptom of haemonchiosis. Blood loss from heavy worm burdens leads to anaemia, weakness, protein loss and sometimes death. Bottle jaw is a classic sign of haemonchosis as fluid builds up underneath the lower jaw.

Infection with Haemonchus can be categorised as either acute, sub-acute or chronic:

- Acute infection is due to high levels of blood loss, resulting in the rapid development of anaemia and death. Acute haemonchoisis is most common in young stock or adults in poor condition that cannot compensate for the blood loss with the rate of production of new red blood cells

- Sub-acute haemonchosis is when blood loss through worm infection is compensated by red blood cell production. This is not maintainable as the bone marrow will become depleted and disease will often become acute

- Chronic haemonchosis is when the host is able to compensate with red blood cell production to a moderate level, although protein loss is gradual as is the loss in condition and pallor

FAMACHA®

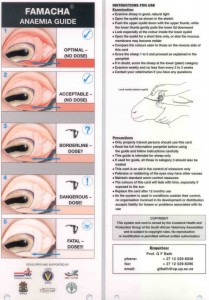

The FAMACHA® scorecard has been developed by a team of researchers in South Africa. It is an eye-colour-chart and is based on the principle knowledge that the colour of mucous membranes is correlated with the anaemia situation of an animal. Anaemic animals are identified and classified using a 1 to 5-colour scale based on the colour of the conjunctiva, and anaemic animals can be selectively treated. They recommend further studies to determine optimal strategies for incorporating FAMACHA®-based selective treatment protocols into integrated nematode control programs. This method has been shown to be an extremely useful tool for identifying anaemic sheep and goats in the southern US and US Virgin Islands (Kaplan et al., 2004). However, studies under low parasite pressure have shown only a low correlation with Haemonchus contortus infection in lambs (Gauly et al., 2004). A review of the system including its application for reducing anthelmintic usage and genetic selection for Haemonchus resistance/resilience can be found at van Wyk and Bath, 2002).

A video guide Why and How to use FAMACHA Scoring has been produced by the American Consortium for Small Ruminant Parasite Control (ACSRPC).

High biotic potential and female worms are fecund

The biotic potential of an organism if the rate at which an organism can reproduce. Under optimal environmental conditions Haemonchus develops very rapidly and the female worms are prolific egg layers producing about 5000 – 6000 eggs per day (Taylor et al., 2007).

Adult stock build little immunity

There is little effective immunity to H. contortus so adults are at risk of disease too. There is some evidence of the development of immunity following a primary infection, but this is not sufficient to provide full protection from clinical haemonchosis (Adams and Beh, 1981). It is also known that some breeds and strains have a degree of immunity to Haemonchus infection . This resistance is inheritable, but only exists in specific breeds and strains and not the whole population, and as such, the general advice on most farms is not to rely on immunity when putting together a parasite control strategy. However, breeding programmes may select for Haemonchus resistance/resilience, e.g. using the FAMACHA system (van Wyk and Bath 2002).

For other gastro-intestinal parasites, such as Nematodirus, sheep develop a strong immunity within 12-18 months, and in such circumstances, immunity can be used to reduce pasture contamination as the adult animals will ingest infective L3 but will not shed vast numbers of eggs. This is not the case with Haemonchus.

Hypobiosis – Overwintering in temperate climates

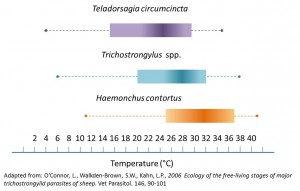

Optimal development conditions for select roundworm eggs to L3 as determined by O’Connor and colleagues. The boxes indicate optimum temperature range, and the dashed lines extend to the upper and lower temperature limits for development. The optimum temperature range for Haemonchus is much higher than other species tested at 25 – 37 °C.

Temperature and moisture are dominant influences on the free-living stages of most GI nematodes but H. contortus in particular is vulnerable to cold temperatures and dry climates (O’Connor et al., 2006).

Unembryonated eggs are most susceptible to cold conditions as the number of viable eggs in faecal pellets maintained at a constant 4°C reduced to less than 1% of the original count in 8 days (Todd et al., 1976).

Haemonchosis is a major problem in goats and sheep in tropical and sub-tropical climates, or regions with summer-dominant rainfall (O’Connor et al., 2006). However it does occur in pockets in temperate zones (Burgess et al., 2012). In these cooler climates most L3 on pasture die during the winter months, however those that are ingested develop to L4 and undergo hypobiosis enabling it to over-winter inside the animal host (Sargison et al., 2007). This is an important feature to consider when purchasing stock in winter as they may not be shedding eggs, but could have arrested larva in their tissues making quarantine drenching new stock particularly important when preventing this worm entering the farm. The best practice guidelines for quarantine new sheep stock can be found on the SCOPS page here.

Due to climate change, an increase of Haemonchus infections in temperate conditions is likely. Using climate change models, Rose et al. (2016) predict that in Northern Europe the period of transmission increases by 2-3 months by 2080.

Haemonchus spp causes disease in cattle

Haemonchus contortus principally infects sheep and goats, but can also be found in cattle and some species of deer and Haemonchus placei is primarily an abomasal parasite of cattle, mainly in tropical and subtropical areas of the world (Anderson, 2000). However, it is also known that both species can simultaneously infect cattle and small ruminants, particularly on communal pastures (Achi et al., 2003; Jacquiet et al., 1998), therefore care must also be exercised in adopting breed interchange (sheep/cattle) schemes in the tropics and the sub-tropics (Waller, 2006). See Control and prevention section below to read which grazing systems are suitable and not suitable for controlling Haemonchus.

Control and Prevention of Haemonchosis

Mixed grazing is often recommended as a method to help dilute L3 on pasture. For nematode species that are host-specific this should work, however on farms with a known Haemonchus problem mixed grazing could be problematic as both cattle and sheep can be infected with this parasite.

Control and prevention of parasitic gastroenteritis relies on an integrated parasite management plan. Full details of the general factors influencing disease and control and prevention can be found on the main parasitic gastroenteritis page. However the grazing management systems that exploit host-specificity such as mixed or alternate grazing of small ruminants and cattle is often recommended as a method to reduce pasture contamination with infective L3 can not be relied on to control Haemonchus (Barger, 1997; Fraser et al., 2007; Marley et al., 2006).

Generally GI nematodes are host-specific, so only infect either small ruminants or cattle, the different types of stock are used to remove infective L3 before putting susceptible stock in, however this is not the case for Haemonchus spp. Haemonchus placei is an abomasal parasite of cattle, primarily in tropical and subtropical areas of the world.

In the more temperate regions this species can cycle in calves, but they rapidly acquire natural immunity to become refractory to infection by 12 months of age (Southcott and Barger, 1975). In the tropics this age resistance is slower to develop, or may never occur. For example, in Paraguay there was no indication that cattle had acquired significant immunity to H. contortus after 2 years of grazing (Benitez-Usher et al., 1984).

In principle good grazing management for PGE in young stock should reduce the risk of build-up of Haemonchus infections to threatening levels, however the general integrated parasite management plan can collapse because:

- Female worms lay lots of eggs, which develop rapidly under optimal conditions

- It is highly pathogenic and relatively low numbers of worms can cause disease

- It doesn’t cause scours, which is a clinical sign farmers relate to ‘wormy’ animals

- Adult stock develop little immunity so adults can suffer from disease too

- It is not host-specific so goats, cattle and deer are at risk too

Haemonchus vaccine

Barbervax® is a Haemonchus vaccine developed by scientists at Moredun that has been trialled and registered for use in lambs in Australia in October 2014. Click here to read the news story.

The mode of action of the Barbervax® vaccine is to trigger the immune system; preventing the establishment of Haemonchus within the host and thereby also reducing the contamination of the pasture by the resulting eggs and larvae, effectively interrupting the lifecycle.

Unfortunately, Barbervax® is untested in goats, and there is currently no estimation as to whether goat farmers may begin to plan to include it in Haemonchus management plans (Kearney, 2016).

In Brazil a Haemonchus vaccine trial in ewes and lambs was undertaken in the tropics and was successful in reducing worm burden and a 75% reduction in egg output by lambs but did not protect periparturient ewes (Bassetto et al., 2014a).

Vaccine trials in 5 month old grazing calves reduced egg output educed the egg output of Haemonchus spp. by 85% and the numbers of H. placei and H. similis by 63% and 32%, respectively, compared with control calves (Bassetto et al., 2014b).

Unlike the other GI nematodes, it is not just the lambs that are susceptible to infection with Haemonchus, ewes and does are at risk too as they build little immunity to this parasite.

Other methods to consider when developing the integrated parasite management plan that would help monitor and possibly reduce haemonchosis which are detailed on the main PGE in ruminants page are:

- Regular Faecal Egg Counts

- Rotational and Evasive Grazing

- Extensive Grazing and Stocking Density

- Cutting and Reseeding Pasture

- Pasture Composition – Bioactive forages

- Strategic Anthelmintic Treatments

Anthelmintic resistance is an active concern internationally, and there is a special need to alter control strategies to take account of this. See the anthelmintic resistance section of the main PGE in ruminants page.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

Tailor the parasite control strategy to the problem parasite species on the farm and include:

- Regular FECs to monitor worm burden in both ewes and does around lambing and lambs and kids post-weaning

- Look out for signs of anaemia – e.g., bottle jaw and FAMACHA

- Use a quarantine does for all new stock

- Do not rely on mixed or alternating stock as a grazing management strategy to minimise haemonchosis

- Consider a strategic treatment of ewes and does around lambing and kidding (2 weeks before and up to 6 weeks after) to reduce pasture contamination using anthelmintics which kill arrested larvae, leaving a proportion of animals (e.g. those with singles in good condition) untreated.

- Check for resistance status using a FECRT

American Consortium for Small Ruminant Parasite Control

For more information on the sustainable control of internal parasites of sheep and goats, we recommend visiting the website of the ACSRPC www.wormx.info. The site contains a range of excellent resources, including videos, very informative fact sheets and technical guidance, scientific papers and other sources of knowledge and advice

American English

American English

Comments are closed.