Sheep Diseases

Mastitis in Sheep

Mastitis is an inflammation of the udder most commonly caused by and infection and in sheep it is considered to be one of the principal reasons (along with lameness) for the culling of ewes. Clinical and sub-clinical mammary infections are considered a welfare issue and are the primary cause of milk drop syndrome in ewes (85% of all cases Giadinis et al., 2012).

In dairy sheep flocks mastitis has obvious financial implications due to the reduction in milk yield, milk quality and rejection of milk if antibiotics are administered. Nevertheless mastitis is also important in meat production flocks as a reduction in milk can cause sub-optimal growth of lambs (Fthenakis and Jones, 1990). Other costs include replacement ewes and vet expenses.

Clinical and sub-clinical mastitis in sheep

Mastitis can occur in both dairy ewes and in meat production systems. Good health status and good nutrition are key in minimizing mastitis and other infections.

Most cases of clinical mastitis in sheep occur in the first week or between the third and fourth weeks of lactation. In some cases, the disease is so severe and rapid that no signs are observed and the animal is found dead. However, these cases are very rare, and usually ewes with clinical mastitis have a swollen, painful udder, generally involving only one ‘half’. The affected half may become red or purple and feels hot, but as the disease progresses becomes cold and clammy. The ewe looks sick, walks stiffly, has a high temperature and becomes isolated from the flock. The lambs may show signs of starvation.

Ewes with lesions from Orf are high risk for clinical mastitis. Learn more about Orf here.

If the ewe survives an episode of clinical mastitis and the signs of illness disappear, any healing of the skin takes several weeks and often part or whole of the affected half may slough.

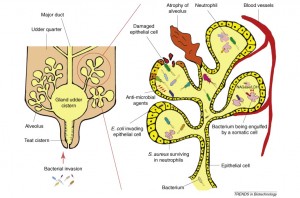

In dairy sheep (and goat) flocks Staphylococcus aureus or coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) are the principle causes of clinical and sub-clinical mastitis, respectively.

Recently, antibiotic-resistant S. aureus is strains have been recognised as an emerging threat to public health. Lollai and colleagues in Italy evaluated 1284 strains of S. aureus from ovine mastitis cases and found a resistant rate of 48-87% against streptomycin, and 2-12% and 0-12 % against penicillin and ampicillin, respectively (Lollai et al., 2008).

Also S. aureus are capable of producing a heat-stable toxin which has the potential to withstand pasteurisation during milk processing. Therefore it should be a high priority to eradicate S. aureus from dairy herds of sheep and goats due to public health concerns (Contreras et al., 2007).

CNS are mostly associated with sub-clinical mastitis in ewes and goats, although they can cause clinical disease (Gelasakis et al., 2015).

Acute and chronic mastitis in sheep

Ewes in indoor lambing systems can be prone to coliform mastitis. It is prevented through good hygiene in the sheep shed (see Control and Prevention of Mastitis in Sheep section below)..

Less severe forms of acute mastitis occur with various forms of secretions. The initial swelling subsides, but varying amounts of udder tissue are permanently damaged, becoming hard and lumpy (Jones, 1991).

Chronic mastitis develops from the acute form of the disease. Single or multiple abscesses and pustules on the surface of the udder may be present. The teat is often swollen to two or three times the normal size, and may contain a hard core of pus. It is usually detected when the ewe is examined at weaning or prior to mating in meat producing systems (Jones, 1991). The mammary gland will often have an asymmetrical appearance.

Streptococcus spp. are sporadic pathogens of ewe mastitis and are usually associated with inappropriate housing conditions or poor milking practices.

In meat production systems, most cases of mastitis are acute and associated with Mannheimia haemolytica, which is a bacteria found in the throats of young lambs.

Coliform mastitis is caused by faecal contamination of the udder and this is prevalent in indoor lambing systems. Regular provision of clean bedding or turning the ewes and lambs out will minimise the risk (Jones, 1991).

Other pathogens

Contagious agalactia (caused by Mycoplasma spp.) can cause intense effects in small ruminants, greatly reduce milk yield, increase SCC, and should be considered a potential pathogen on farm where sub-clinical is endemic.

Nocardia spp has also been considered as an important pathogen, and is known to cause mastitis in goats (Berriatua et al., 2001)

Maedi-Visna virus (MVV) is a small ruminant lentivirus which can also cause mastitis (Monleón et al., 1997).

Diagnosis of mastitis in ewes

Diagnostic procedures for mastitis include clinical examination (swollen painful udder, or obvious teat lesions, abnormal milk, high rectal temperature, lameness not associated to lesions on the limbs), bacterial culture and screening of individual and /or bulk milk tank milk samples. The gold standard is increased milk-SSC coupled with bacterial isolation (Gelasakis et al., 2015).

Selective bacteriological testing serves to cut the cost of extensive sample collection. Usually one (ideally, post-milking) sample is all that is needed for a positive diagnosis. However, consecutive positive samples from the same udder half is better and as this should minimise false-negatives. Mammary pathogens can remain viable in frozen milk samples for longer than the lactation period and thus can be used in a mastitis control programme.

Control and Prevention of Mastitis in Sheep

Control of mastitis requires high standards of hygiene both in the shed and during milking, balanced ewe nutrition, and regular on-farm monitoring of the ewes as this provides an indication to the general health status and in particular mammary health status of the ewes.

Ewes affected by mastitis should be segregated and culled so as to minimise the spread of infection from cross sucking (Scott and Jones, 1998). Culling ewes prone to infection at the end of the lactation period will contribute to reducing incidence of mastitis in the flock, this will also reduce vet bills, eliminate a potential source of infection, and decrease bulk milk SCC (Gelasakis et al., 2015).

Hygiene in the sheep shed – issues such as insufficient clean straw/bedding, poor ventilation, lack of regular removal of faeces, inadequate disinfection of the shed all contribute to poor hygiene in the shed as they all lead to the build-up of environmental pathogens.

Milking practice – Incorrect milking practices, poorly trained staff, over-milking, insufficient cleaning of milking equipment, over-use of liners, poor water hygiene and malfunctions of the milking machine (incorrect vacuum, pulse rate and ratio) all led to pathogen build up and are potential causes of mastitis. Regular checking of the milking equipment, good milking protocol (including post-milking teat dipping) and regular observations of the udders all help in minimising ewe mastitis.

Feeding ewes – Vitamin A deficiency has been identified in cases of clinical and sub-clinical mastitis (Koutsoumpas et al., 2013). As has selenium deficiency (Giadinis et al., 2011).

Udder conformation – teat placement and udder shape may be linked to mastitis incidence. Machine milkability of such udders is difficult, the cluster often fall off, milk may be retained in the teat canal, thus requiring further stripping (Gelasakis et al., 2012).

Number of suckling lambs – The more lambs suckling from the ewe, the more chance of transmission of M. haemolytica. Also lambs from infected mothers will endeavour to suckle other ewes to supplement their own mothers’ milk thereby spreading infection throughout the flock (Contreras et al., 2007). Additionally, ewes with multiple lambs will encounter more suckling events with longer suckling periods and an increased risk of teat bites and lesions, and therefore potential colonisation of bacteria in the udder causing mastitis (Gelasakis et al., 2015).

Health status – immunocompromised animals are more susceptible to diseases, including mastitis. Stress can affect the health status of ewes. The phenomenon known as ‘peri-parturient relaxation’ which is when the immunity in ewes is thought to ‘relax’ in the weeks pre- and post-lambing may also be responsible for some cases of mastitis seen immediately after lambing. In general overall high health status of ewe will support in controlling mastitis by preserving good immunity (Gelasakis et al., 2015).

Treating Mastitis in Ewes

Acute mastitis is a welfare issue in ewes and can often go unnoticed in sheep. Successful treatment relies on early intervention, therefore regular observation of the ewes, and in particular of her teats and udder is important to avoid suffering and to increase the chances of effective treatment.

Mastitis in ewes often goes unnoticed in the early stages of the disease, and for this reason the affected half is often damaged and lost to milk production. Furthermore, as affected ewes are often very sick when observed, there is usually no time to determine the organism responsible and its antibiotic sensitivity.

In flocks in which there is a high incidence of mastitis, the teats and udder should be examined regularly, and any lesions present treated immediately to prevent infection.

Effective treatment relies on early intervention and efficacy. Antibiotics can be administered to treat the infection, and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent to combat pain is recommended. However, to preserve the efficacy of antibiotics, only ewes suspected of mastitis should receive antimicrobial agents based on clinical examination and a possible milk sample (Gelasakis et al., 2015).

There is no effective treatment for chronic mastitis, and the affected ewes should be culled.

Mastitis in Ewes and Welfare

Mastitis in sheep is also a great welfare concern. Clinical disease can lead to anxiety, restlessness, changes in feeding behaviour, and pain in affected ewes (Fthenakis and Jones, 1990). In sub-clinical mastitis normal behaviour of ewes is also altered hence raising potential welfare implications. Mastitis in sheep can go unnoticed until the animal is very sick. Therefore, good stockmanship and regular inspection of the ewes is essential to avoid suffering.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

- A well-designed milking protocol is important in preserving the udders. Rough handling during milking can lead to teat injury (Contreras et al., 2007).

- In flocks with a mastitis problem, reducing the incidence should be part of the overall flock health plan

- Flocks with a coliform mastitis problem need to change their management by improving environmental hygiene and reducing stock density. Also providing more clean bedding and/or putting the animals outdoors if the weather permits

- In flocks with a high incidence of mastitis, the ewes’ teats and udder should be inspected regularly for lesions

- Cases of orf in ewes with young lambs should be isolated to avoid the further spread of orf by cross sucking and treated with topical antibiotics to prevent secondary infections

- Isolate affected ewes to avoid spreading the disease through cross sucking

- Clinically affected ewes should be treated immediately by a vet with broad spectrum antibiotics as there is often no time for the identification of the infective agent

- Cull ewes with chronic mastitis

Contreras, A., Sierra, D., Sánchez, A., Corrales, J.C., Marco, J.C., Paape, M.J., and Gonzalo, C. (2007). Mastitis in small ruminants. Small Rumin. Res. 68, 145–153.

Fthenakis, G.C., and Jones, J.E.T. (1990). The effect of experimentally induced subclinical mastitis on milk yield of ewes and on the growth of lambs. Br. Vet. J. 146, 43–49.

Gelasakis, A.I., Arsenos, G., Valergakis, G.E., Oikonomou, G., Kiossis, E., and Fthenakis, G.C. (2012). Study of factors affecting udder traits and assessment of their interrelationships with milking efficiency in Chios breed ewes. Small Rumin. Res. 103, 232–239.

Gelasakis, A.I., Mavrogianni, V.S., Petridis, I.G., Vasileiou, N.G.C., and Fthenakis, G.C. (2015). Mastitis in sheep – The last 10 years and the future of research. Vet. Microbiol. 181, 136–146.

Giadinis, N.D., Panousis, N., Petridou, E.J., Siarkou, V.I., Lafi, S.Q., Pourliotis, K., Hatzopoulou, E., and Fthenakis, G.C. (2011). Selenium, vitamin E and vitamin A blood concentrations in dairy sheep flocks with increased or low clinical mastitis incidence. Small Rumin. Res. 95, 193–196.

Giadinis, N.D., Arsenos, G., Tsakos, P., Psychas, V., Dovas, C.I., Papadopoulos, E., Karatzias, H., and Fthenakis, G.C. (2012). “Milk-drop syndrome of ewes”: Investigation of the causes in dairy sheep in Greece. Small Rumin. Res. 106, 33–35.

Jones, J.E.T. (1991). Mastitis in sheep. In Diseases of Sheep, W.B. Martin, and I. Aitken, eds. (Wiley-Blackwell), pp. 75–78.

Koutsoumpas, A.T., Giadinis, N.D., Petridou, E.J., Konstantinou, E., Brozos, C., Lafi, S.Q., Fthenakis, G.C., and Karatzias, H. (2013). Consequences of reduced vitamin A administration on mammary health of dairy ewes. Small Rumin. Res. 110, 120–123.

Lollai, S.A., Ziccheddu, M., Di Mauro, C., Manunta, D., Nudda, A., and Leori, G. (2008). Profile and evolution of antimicrobial resistance of ovine mastitis pathogens (1995–2004). Small Rumin. Res. 74, 249–254.

Monleón, E., Pacheco, M.C., Luján, L., Bolea, R., Luco, D.F., Vargas, M.A., Alabart, J.L., Badiola, J.J., and Amorena, B. (1997). Effect of in vitro maedi-visna virus infection on adherence and phagocytosis of staphylococci by ovine cells. Vet. Microbiol. 57, 13–28.

Scott, M.J., and Jones, J.E.T. (1998). The carriage of Pasteurella haemolytica in sheep and its transfer between ewes and lambs in relation to mastitis. J. Comp. Pathol. 118, 359–363.

American English

American English

Comments are closed.