Sheep Housing

Housing of sheep is normally carried out either to protect the animals from predators or harsh weather, to provide additional feeding or to reduce losses at lambing. An increasing number of lowland, upland and hill flocks are housed, either over the whole period or for a restricted period around lambing. Sheep do not particularly need housing, provided they are of the right breed for the conditions and have access to sufficient nutrition. Sheep are capable of living outdoors at very low temperatures. The temperature at which they can comfortably live outdoors in very cold climates will depend on wool length and level of feeding, although the degree of heat loss will also be influenced by wind strength and rainfall (Berge, 1997).

Housing of sheep is normally carried out either to protect the animals from predators or harsh weather, to provide additional feeding or to reduce losses at lambing. An increasing number of lowland, upland and hill flocks are housed, either over the whole period or for a restricted period around lambing. Sheep do not particularly need housing, provided they are of the right breed for the conditions and have access to sufficient nutrition. Sheep are capable of living outdoors at very low temperatures. The temperature at which they can comfortably live outdoors in very cold climates will depend on wool length and level of feeding, although the degree of heat loss will also be influenced by wind strength and rainfall (Berge, 1997).

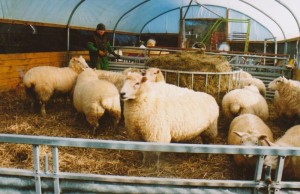

The type of housing we use for sheep can vary from simple shelters to purpose built, permanent structures, depending on whether sheep are housed for significant periods over winter periods or for short periods during lambing. Given that our aim is to promote land-based, outdoor systems using breeds adapted to the climatic conditions, the period that sheep are housed should be minimal and to provide necessary shelter during inclement weather and/or to ensure that we minimize losses during lambing. However, there are occasions when housing can provide better conditions for management, including disease diagnosis, health care, feeding, watering and in particular, assistance at lambing. Housing ewes at lambing can reduce the risk of stillbirth (Binns et al., 2002). There is also the possibility that housing reduces pasture and soil damage. With regard to predation control, there will be predator and regional variations, but it has been shown that housing sheep to protect from fox predation is not necessarily economically beneficial in England (Moberly et al., 2004).

Health at Housing

If a flock already suffers from infectious disease problems, then housing such a flock is likely to magnify the problems as the stocking rates are increased. Enzootic (chlamydial) abortion, campylobacter abortion, border disease, footrot, pasteurellosis, jaagsiekte, maedi visna, Johne’s disease and keratoconjunctivitis are all important. Another problem, which has increased over recent years simultaneously with housing, is listeriosis caused by feeding poor quality silage. However, closer observation indoors makes some problems, such as prolapse, acidosis, pregnancy toxemia and hypocalcemia, easier to detect and treat.

Recently, it has become more common to shear housed ewes in winter. This reduces heat stress and has been shown to increase birthweights of lambs. However, while reducing the risk of heat stress, winter shearing will make the ewe more prone to cold stress and energy deficiency in adverse weather conditions. Berge (1997) recommends shearing 6 weeks before lambing as it gives better feed intake, weight gain and newborn lamb weights even if the outside temperatures well below zero.

Handling Systems

We handle sheep for either health maintenance reasons (e.g. vaccination, dipping, foot-bathing, foot-paring and de-worming) or for management and production purposes such as shearing, weaning or classifying by age, sex, weight for marketing purposes. The general design principles for handling systems should accommodate and exploit the behavioral characteristics of sheep (Hargreaves and Hutson, 1997).

We can think of the effectiveness of a handling system in a number of ways, including:

We can think of the effectiveness of a handling system in a number of ways, including:

(1) the degree to which the animal must be restrained

(2) the extent to which the procedure causes distress to the animal

(3) the facilities or labor input required

(4) the effectiveness in undertaking the key health and production related functions

(Hargreaves and Hutson, 1997).

Vision is a particularly important consideration in the design of handling facilities, as sheep have acute eyesight with a wide visual field of about 270o, of which about 50o of this is stereoscopic (three dimensional) vision. Visual cues that inhibit movement should be avoided. Even though sheep show reluctance to cross drains and shadows, contrary to common belief they probably have good depth perception and their reluctance is related to a perception of discontinuity causing the head to lift suddenly, with vision then being blocked by the animal’s muzzle (Hargreaves and Hutson, 1997).

In terms of hearing, sheep are most sensitive to sound at a frequency of 7000 Hz, whereas humans are most sensitive to sounds in the range 1000 to 3000 Hz (Ames and Arehart, 1972). They are sensitive to irregular noise and it has been proposed that the soothing sound of music at handling facilities can reduce stress (Grandin (1980)).

Design Principles

Several principles for the design of handling facilities are set out by Hargreaves and Hutson, 1997:

- Sheep movement should be across rather than up or down inclines

- There should be adequate surface drainage and a firm footing

- Lighting should not cast shadows across the path of the sheep

- The construction materials should not make loud or alarming noises when they are being used

- Avoid uneven sides on fences and gates that cause wool, legs or horns to become caught, or impede movement, or encourage sheep to jump

- Moving parts, such as gates and catches, should be simple, sturdy and easily operable

- Sheep movement should be directed to attractants such as other sheep or the exit rather than to aversive features such as treatment areas or dead ends or humans or dogs.

Breed Differences at Handling

There are distinct differences in the way different breeds react during handling, particularly with regard to the tolerance to humans and dogs and the resistance to physical restraint. For example, the Rambouillet sheep tend to bunch tightly together and remain in a group, compared with crossbred Finn sheep that tend to turn, face the handler, and maintain visual contact until the handler penetrates the collective flight zone when they then turn and run past the handler . In a comparison, the Cheviot and Perendale breed were are classed as being the easiest to drive into a crowding pen with the Romney, Merino-Romney cross and Dorset-Romney cross being the most difficult. Romney sheep have been shown to be most likely to follow the flock leader and also the most easily led into blind corners. The Cheviot breed have a strong instinct to maintain visual contact with the shepherd and show more independent movements than other breeds. These examples are cited by Grandin (1980). There are also significant breed differences in a scale of gregariousness, with the Merino breed being the most social compared with the Scottish Blackface at the other end of the scale (cited by Hargreaves and Hutson, 1997).

For more information relating to behavior at Housing and Handling visit the following pages:

Shepherding

Sheep Behavior

British English

British English

Comments are closed.